By Rob Kesselring

Take a drive to the end of the Gunflint Trail and spend a few hours at Chik-Wauk Museum, the word serendipity will come to mind. Could there be a better place for a museum and nature center that celebrates the human and natural history of the Quetico Superior Wilderness than at the end of the Gunflint Trail? And what good luck that so many different biomes are represented on the museum grounds that even wheelchair-bound visitors can experience a breadth of biodiversity traveling two of the six carefully maintained trails!

Chik-Wauk was originally a fishing lodge, but although many lodges were built in Northeast Minnesota, few took on aboriginal names. Chik-Wauk was an attempt to adopt the Ojibway name for white or possibly jack pine. This respectful gesture by the old lodge founders has appropriately become the name for the new museum.

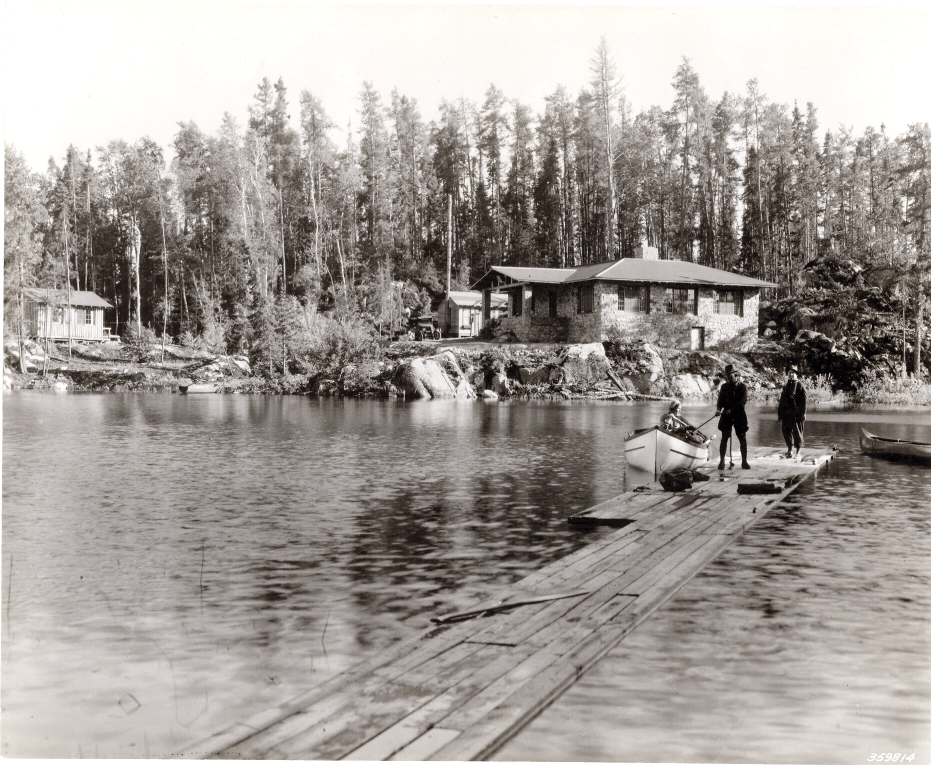

But, Chik-Wauk’s history, like many initiatives in the wilderness of the border lake country, was a bit of a bumpy road. After a couple years of housing summer fishermen in a campy lodge built on the edge of the Gunflint Trail, Ed Nunstedt built a fine wooden building with a stone porch at the present site in 1932. But on May 19th of 1933 before even the first guest arrived, a pet dog knocked over a kerosene lamp and the lodge burned to the ground. Only the stone porch was left standing. The lodge was rebuilt again, this time entirely of granite so

it wouldn’t burn again and providentially because several Duluth stonemasons, unemployed by the Depression, jumped at the chance for work in exchange for room and board. Had it been rebuilt of logs it likely would have been moved after the Wilderness Act, or burned, or would have deteriorated beyond repair. But the stone structure, like the Canadian Shield which it celebrates, endures.

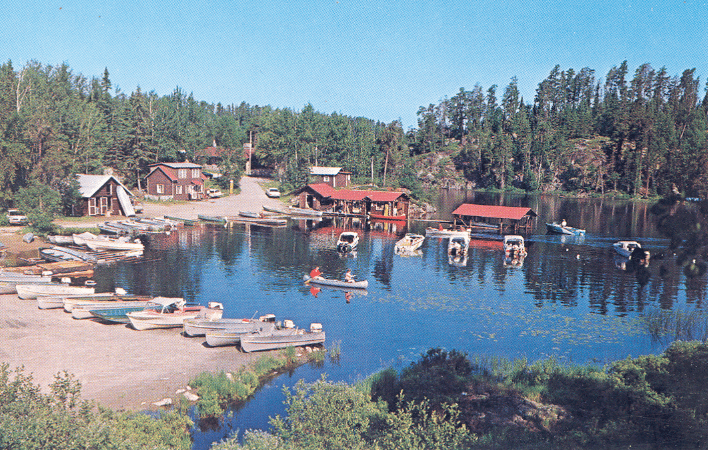

There are more serendipitous events. Situated at the end of the Gunflint on Saganaga Lake, Chik-Wauk Lodge was historically a gathering place for residents on both sides of the international border. It was the place local Canadians and Americans bought groceries, picked up their parcels, and mailed letters. Although they might have come from different countries it was at Chik-Wauk where they shared the stories of their lives in the wilderness. When talking to their neighbors, however distant, about issues with bears, storms and ice they experienced that reassuring feeling of–“What, you too?” Chik-Wauk was their link to civilization and to each other. And today, it appropriately stands as a link to the past. This history of common experience and sense of community has been renewed and strengthened by the residents of the Gunflint Trail in partnership with the U.S. Forest Service, and with donations from Canadian neighbors who have worked hand-in-hand to create a spirit of pride, cooperation and wonder that is palpable as you enter the quaint stone building.

It’s not as if the museum was built in just an old abandoned building; many threads connect the past to the present. Ralph Griffis, the last owner of Chik-Wauk Lodge and a summer resident until 1998, was dismayed when he learned that the Museum had not replaced the old flagpole. This was remedied in the spring of 2011 when a flagpole was installed in front of the museum. At a time when there is so much concern about international border security the Gunflint Trail Historical Society is considering flying both the stars and stripes and the maple leaf as a reminder of times when travel across borders was more casual. They are soliciting public input on this issue on the Chik-Wauk web site blog at Chikwauk.com.

If you think of a museum as a stuffy institution to which a visit is more endured than enjoyed, you will be surprised at Chik-Wauk.

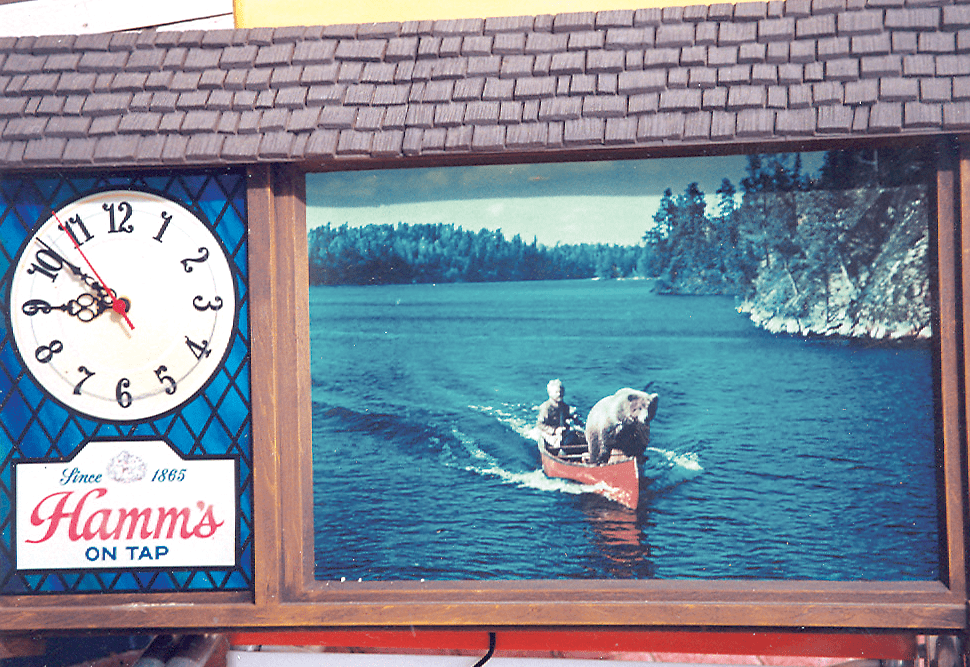

Midwesterners will remember those early and corny television ads for Hamm’s Beer. The jingle that stuck in your head, “From the land of sky blue waters” and the accompanying visual of the grizzly bear perched in a canoe was filmed, of course, at Chik-Wauk Lodge. Old beer ads and memorabilia are unabashedly displayed in the museum along with an interactive exhibit where participants can hoist a voyageur’s load on their backs. Panels with information supplied by the Gunflint Historical Society and the Forest Service, and artfully designed by Split Rock Studios, a graphic arts company, grace the walls. Dioramas and murals documenting natural history, prehistoric artifacts and interesting relics from the days of voyageurs, miners, loggers, resorters and canoeists are all packed into the small museum, but remarkably the space seems fresh and not cluttered. In its 2010 inaugural season almost 11,000 visitors passed through the doors of the museum. Ada Igoe, site manager and the only paid employee at Chik-Wauk, will tell you that only on a few rainy days last summer did it ever feel crowded in there! Although the displays, maps and exhibits are comprehensive, artistic and informative, a few other features truly distinguish the museum. Each year there is a temporary exhibit such as, “The construction of the Gunflint Trail.” This changing exhibit helps keep the museum fresh. Also, during the busy season, guest speakers present in what was the main lounge of the lodge on a variety of historical, natural or cultural topics. Behind the fireplace is the main theater with three on-demand films available with a press of a button: The History of the Gunflint Trail, The Voyageurs, a National Film Board of Canada documentary, and, Lady of the Gunflint, a PBS produced Justin Kerfoot documentary.

In two corners of the museum there are touchscreen television monitors, where visitors can select from a wide range of 2-minute movies. One screen concentrates on past and present Gunflint area businesses. The other screen focuses on a list of pioneers and colorful characters of the region.

The Forest Service has not always been welcome at the same table with the local residents. It was, after all, the responsibility of the Forest Service to impose the mandates of the Wilderness Act, mandates that in many ways profoundly changed the lives of these residents. The Chik-Wauk Museum initiative, however, was a cooperative project with members of the Gunflint Trail Historical Society and other local volunteers working and making decisions together with the Forest Service. Many volunteers have helped establish the museum, but past presidents of the Gunflint Trail Historical Society, Betty Hemstad and Sue Kerfoot, and current president, Fred Smith, spearheaded the effort. Forest Service expertise was crucial in the successful application for Chik-Wauk to be listed on the National Registry of Historic Buildings in 2007. The only other Gunflint Trail building on the Registry is Clearwater Lodge.

Adaptive reuse is a concept the Forest Service brought to the museum. The idea was to modernize the facility for safety and convenience while preserving the character of the time period when the building was constructed and initially utilized. This gives visitors not only information about the past but also a chance to experience the feelings of bygone eras. Many of the visitors in the summer of 2010 were past guests at the Chik-Wauk Lodge, and having the opportunity to recreate old memories is a powerful gift. The Forest Service brought its expertise and support to the project, but the stories and the elbow grease came from the people of the Gunflint. Superior National Forest Archaeologist Lee Johnson calls the development of the museum a fine example of collaboration, cooperation and good fun for a common and positive goal. Visitors will conclude that the partnership has succeeded.

Most of all, if during your exploration of the exhibits you have a question, ask Ada or one of the volunteers. Odds are you will hear a story that will be the highlight of your experience at Chik-Wauk.

This article appeared in Wilderness News Summer 2011