In an era of increasing partnership in the Quetico Superior region, the Border Lakes Partnership provides a model for what cooperative efforts can accomplish.

The collaborative has been at work since 2003 developing cross-boundary strategies for managing forest resources, reducing hazardous forest fuels, and conserving biodiversity in the region. Members like the U.S. Forest Service Northern Research Station, Superior National Forest, Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, Voyageurs National Park, Quetico Provincial Park, and The Nature Conservancy have worked to identify land management options that will help its partners achieve mutual goals.

The Border Lakes Partnership is set to release the first fruits of its efforts this fall: the results of a modeling study aimed at determining the potential effects of timber production, fire management, and natural disturbance on the Quetico Superior landscape. A draft of the report suggests forest management activities that cross jurisdictional boundaries could indeed yield mutually desired ecological and socio-economic objectives.

Post-doctoral researcher Doug Shinneman, who led the Border Lakes Partnership modeling project, said the collaborative effort was unique in the Midwest and uncommon overall.

“It’s not that there aren’t other collaboratives that are interested in similar types of objectives,” he said. “I think one of the things that makes this collaborative unique is that the interested parties got together because of a sense of common purpose. In other cases, some of these more collaborative groups that have worked across agencies have gotten together because there’s been conflict or issues they needed to resolve.”

Shinneman, himself, embodies the shared nature of the Border Lakes Partnership’s efforts. “My position is really a unique one,” he said. “It is a joint position between The Nature Conservancy and the USFS. Thus, while I am technically a TNC employee, I am housed at the Northern Research Station here in Grand Rapids, and I really work for both organizations.”

Initial efforts to have stakeholding agencies and organizations in the region work together predated Shinneman’s arrival to the Quetico Superior. The group’s formation can be traced to a 2003 workshop where many of the current members gathered as part of The Nature Conservancy’s Fire Learning Network to discuss issues related to fire ecology and fire safety. Shinneman began work on his project in 2006.

Shinneman notes that the Border Lakes Partnership now generates technical materials that support the broadly-based Heart of the Continent Partnership, which gathers a larger collection of regional stakeholders and is focused on more than just collaborative research and forest management.

The 111-page Border Lakes Partnership report titled “Exploring Collaborative Options Restoring Forests and Reducing Fire Risk in the Border Lakes Region,” authored by Shinneman, Cornett, and the Northern Research Station’s Brian Palik owes its existence to the original collaborative effort in the region.

The study, funded by the USFS National Fire Plan, computer-modeled the effects of various forest management regimes on forest health and composition. Shinneman and his colleagues wanted to know whether cross-boundary management plans could affect outcomes on the landscape that would be socially and ecologically beneficial.

“We were curious about the trajectory we’re on now – the current types and levels of fire management, fire suppression, timber harvest, and so on – where was that going to take our landscape 100, 200 years from now – or ten years from now, for that matter – versus other possible alternatives” Shinneman explained. “And those other alternatives included options like coordinating our management.”

As it is now, the Quetico Superior is a 5 million acre landscape managed by an array of local, state, provincial, and federal agencies in both the United States and Canada. Shinneman’s team wondered if management which crossed jurisdictional boundaries could help develop a Quetico Superior landscape that met more of the ecological and economic needs of the region.

“The agencies themselves had recognized that that was a direction they were interested in going, and there had been some talks and consideration of having, say, fires burn across the border between Quetico and the United States,” Shinneman said.

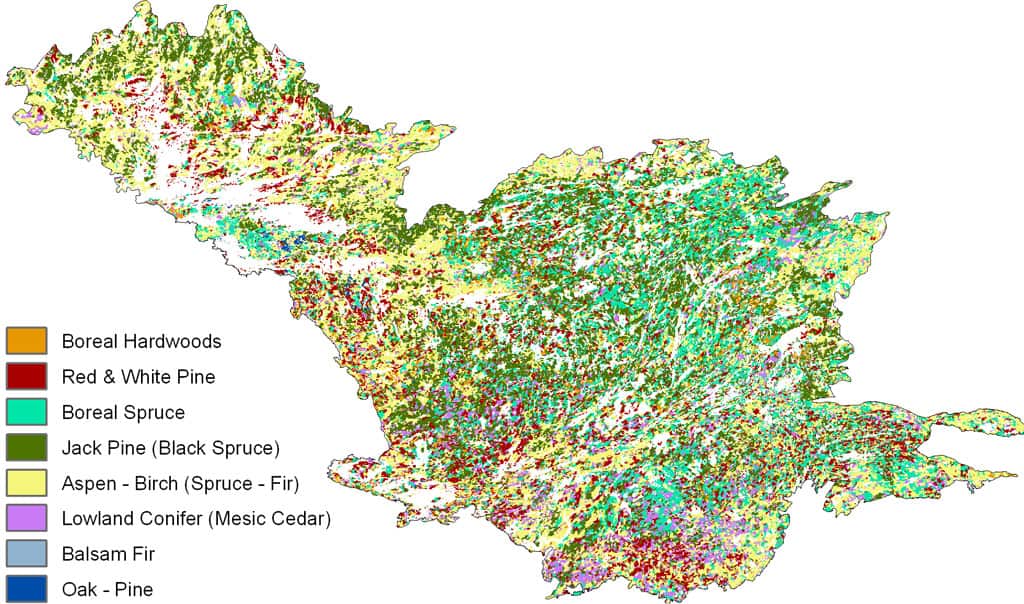

Shinneman modeled five management scenarios for the region: a “Current Management” scenario that reflected current fire suppression and timber harvest policies, and four “Restoration Management” scenarios that included greater use of fire, timber harvest that emulated natural disturbance patterns, and cross-boundary co-ordination. Two additional scenarios were modeled for comparison purposes, to distinguish the effects of fire from timber harvest. A “Natural Disturbance” scenario was simulated to reflect pre-settlement disturbance patterns, and a “Contemporary Natural Disturbance” scenario to reflect natural disturbances within the context of current fire suppression policies.

Shinneman and members of the Border Lakes Partnership were eager to see if management practices that more closely mimicked natural disturbance – namely, allowing more fires to burn in wilderness areas and designing and concentrating clear-cuts to mimic the size and footprint of natural disturbance – would create a long-term trajectory that could lead to a more historically representative forest.

Researchers and managers were especially keen to see if jack pine regenerated at its historical rate and if red and white pine forests could be conserved. They wondered, too, if their techniques would establish a less bifurcated landscape – today, early successional species like aspen dominate many areas outside the BWCAWand Quetico and late-successional spruce-fir forests are increasingly dominant in the

wilderness areas.

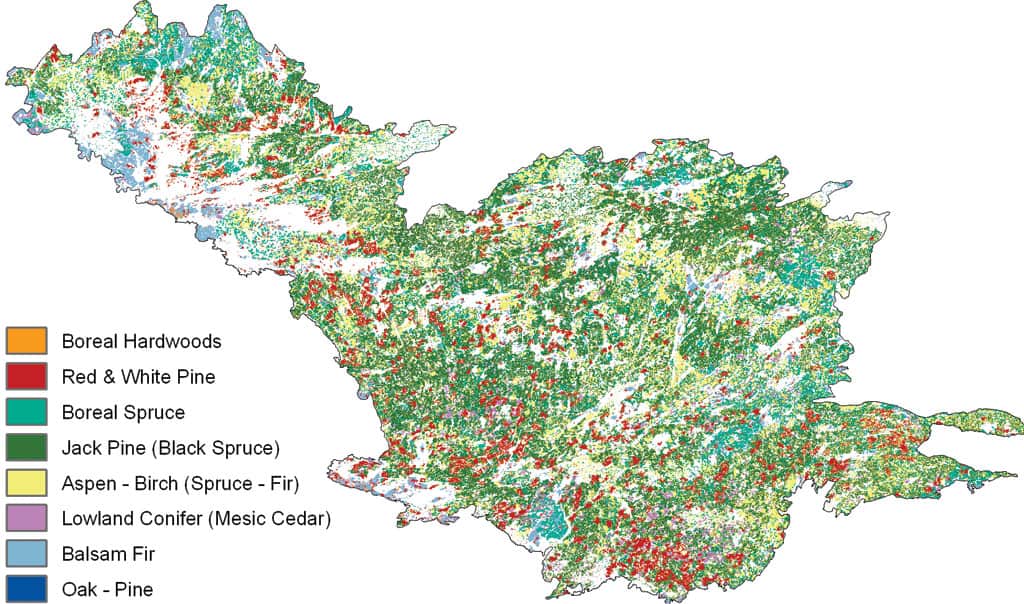

A Model of the Quetico Superior in 200 Years: The modeled results of the “Restoration Management” regime where timber harvest mimicked natural disturbance patterns and ignored management boundaries and where a prescribed fire zone straddled parks and wilderness area boundaries. (White areas that are not lakes represent recently burned regions.)

The model’s results were instructive. “More fire does help to restore these forests – relatively quickly, in terms of 100 to 200 years – to a more jack pine dominated southern boreal forest type,” Shinneman said. “That’s high-severity fire. Low-severity fire, that was limited to red and white pine areas which is the historical fire regime for those types, maintained those patches of red and white pine on the landscape.” Keeping red and white pine in its historic place on a future landscape proved difficult, however.

“None of the scenarios protected red and white pine very well,” Shinneman admitted. “I think that’s because it’s already so greatly reduced and scattered on the landscape that indiscriminant harvest or stand-replacing wildfires that burn across the landscape are going to take out some of the remaining red and white pines. Despite efforts to return low-severity fire in some of these stands and using silvicultural techniques to keep them on the landscape, other things were going on that caused them to decrease.”

Shinneman cautioned that both the hoped-for conditions and the less desirable results of the study aren’t certain predictions for the future. Computer models are only as sound as the information provided to the model. No model can take into account all the factors that impact something as complex as a 5 million acre forest.

“Modeling is just a way to look at possibilities,” Shinneman cautioned. “Models are always wrong to some extent. The questions is, are they useful, do they tell you something, do they give you an indication of potential affects of these kinds of dynamics? Do they give you some sense of where we’re heading in the future?”

By Charlie Mahler, Wilderness News Contributor

This article appeared in Wilderness News Fall 2008