By Julie Neitzel Carr

Trekking the Boundary Waters, my portages followed a predictable path; I would double-check the distance on my map, hoist up a heavy Duluth pack, or if it was my turn, the canoe, grab the remaining miscellaneous gear (fishing rods, life jackets, paddles), take a deep breath and with my head down, push forward. I would count my number of steps, trying to estimate how many rods I’d hiked and how many remained. If it was a portage where I’d have to double back I would keep an eye out for landmarks that would remind me how far I’ve come, or need to go. I sang songs, recited poems and sometimes mindlessly counted. If I did observe anything it was scat on the trail. I would wonder if there are bears or wolves watching me pass and I would worry that they might think that I was a weak link in the circle of life. I would shudder and move forward step-by-step, anxious for the next lake to show itself. The goal: to take this heavy load off my shoulders and get back on the water.

But not anymore, that mode of wilderness travel ended last spring. A June experience has changed me. I discovered the birds of the BWCA. It happened when I enrolled in a field class, Bird Ecology of the Northern Forest.

Before this class, my reports of the wildlife would include moose, loons, beavers, river otters and bald eagles all of which I saw while gliding across lakes in my canoe. I would even evaluate my trips based on whether or not I saw a moose. What I never did was give much attention to the lives playing out above me in the forest canopy. The class changed my perspective and broadened it forever. Instead of focusing on the water and the ground, we spent the weekend looking up and listening to the songs, calls, and chirps of the birds that I discovered surrounded us. We learned about the migrations, habitats, mating rituals, feeding behaviors and flight patterns of the warblers, waxwings and vireos. I learned that Sawbill Lake is named for the Common Merganser also known as the Sawbill due to the shape of its beak, and we saw many of them. I got so busy studying the birds that I forgot about the wolves and bears and, more than that, learning about bird ecology changed my attitude. I feel less fearful, more confident and respectful.

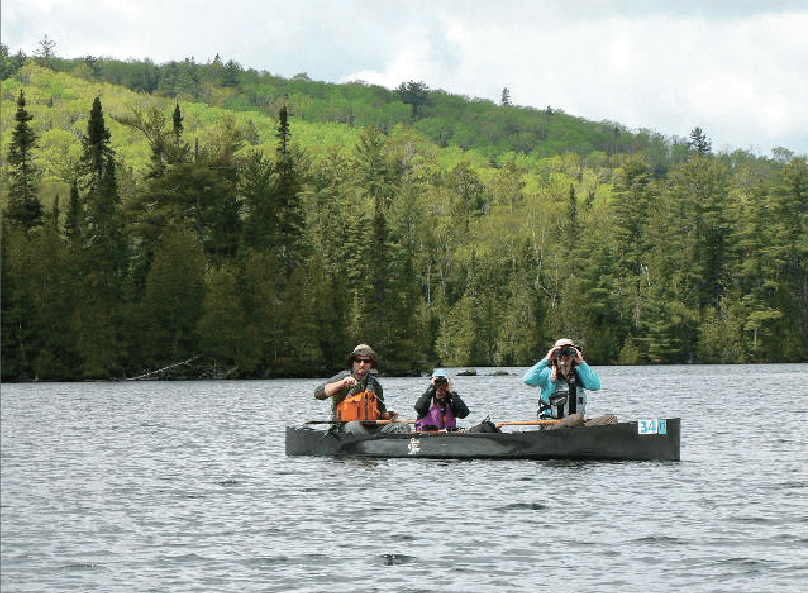

A classroom in the great north woods is a unique experience. It’s alive. After our breakfasts we would pack up and head out in field either by foot or canoe. Sue Plankis, one of our two instructors, wanted to observe a specific area, which has been designated by the Minnesota Breeding Bird Atlas as a priority block. Our sightings of evidence of nesting and breeding birds would be entered into the 5-year study. Our quest took us through the women’s chain. This time on the portages, I took my time. I looked up instead of at the ground. Instead of singing to myself, I listened to the songs of birds, stopping often to listen, really listen. Our guides helped us differentiate and soon we knew the distinctive calls of the Chestnut-sided Warbler, the Northern Waterthrush and the ubiquitous White-throated Sparrow. I flushed a Ruffed Grouse from the brush and upon further exploring we found its nest. Another amazing moment was the observation of the uncommon Black-backed Woodpecker. Not only did we observe this bird, we also learned its distinctive feeding behavior of flaking bark in its search for insects. On the way back to camp, a Merganser swooped down in front of my canoe close enough to touch; the Sawbills had become my friends.

We spent the evening fireside with our cocoa discussing the birds we saw during the day, who was in the lead for spotting AND correctly identifying the most birds (our final grade depended on this – not really, class atmosphere was casual and friendly, but we teased a lot). We looked at our field guides and listened on the ipod to different bird calls that helped us remember the distinct calls of the birds we had observed that day. In the midst of our discussion we heard some of the wild warblers answer back to our recordings. That would never happen in a mortar and brick classroom!

Later in the summer I returned to the BWCA with my husband and children and discovered that my greater appreciation for the life and sounds of the forest canopy had persisted. I now hear individual songs instead of random chirps and tweets. I know to look deeper on the limbs and to identify different species by their flight pattern or feather markings. Although I pack ultralight I will never travel the Boundary Waters again without my bird guide. I’ve also concluded that what my co-instructor in the bird ecology class, Rob Kesselring, said is true: that preservation of the wilderness depends on knowledge and experience, “You’ve got to know it and to live it!” Discovering the birds of the northern forest has enriched my wilderness experience and has drawn me closer to nature, which is really my purpose of going to the BWCA.

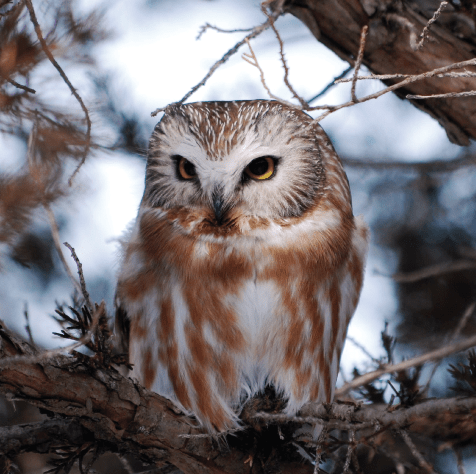

One last nature note: At the conclusion of our June class while coming out of the BWCA at Sawbill Campground we overheard campers complaining about the beep, beep, beep, of trucks backing up during the night. Those were not trucks! They were the breeding calls of Saw-whet Owls. I never would have known this prior to the class and I will be forever richer for that knowledge.

Uncommon Seminars LLC leads classes every summer in the BWCA e-mail info@uncommonseminars.com for more information.

This article first appeared in Wilderness News Spring 2012