What the insect could mean for the Quetico Superior Region

By Charlie Mahler

When emerald ash borers, the bright green invasive insects that have decimated ash trees across the southern Great Lakes region, were discovered in Houston County and St. Paul, Minnesota this spring, resource managers and tree owners in southern Minnesota shifted into high gear in attempt to contain the formidable pest. In northern Minnesota, too, far from current infestations, foresters and land managers are bracing for the seemingly inevitable spread of the insect to their part of the state, where the vast majority of Minnesota ash trees grow.

To slow the spread of emerald ash borers into the Superior and Chippewa National Forests, U.S. Forest Service officials have announced rules restricting the transport of firewood from other states and from infested regions of Minnesota. Any firewood brought into the forests must be purchased from certified firewood vendors. In Canada, authorities discourage the transport of firewood, but have not imposed mandatory restrictions outside of the quarantine areas where outbreaks have occurred. Infestations in Canada have so far occurred well to the east of the Quetico Superior region.

The insects, first noticed in Michigan in 2002, have destroyed ash trees from Maryland to Wisconsin. Once established, the insect—originally native to eastern Russia, northern China, Korea, and Japan—can cause 100% mortality to ash trees. A female ash borer lays eggs on the bark of an ash tree in summer. A white-colored larva emerges and burrows into the bark, where it eats the living wood and cuts off the vessels that carry water and nutrients between the roots and the leaves. After the larva morphs into a pupa and exits the tree through a signature D-shaped hole, the damage is done. Trees typically succumb to the damage in two to three years.

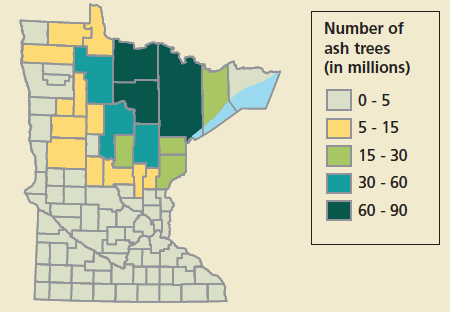

The Ash of the North

Black ash, the primary ash species in the Quetico Superior area, inhabits wet, lowland areas with mucky, mineral soils. While not particularly abundant in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness or Quetico Provincial Park, black ash forests account for 540,200 acres of Minnesota’s forests – roughly half the acreage of the BWCAW, by comparison. The tree comprises 50% of the state’s lowland hardwood forests, with a range extending from the Mason-Dixon Line north to western Ontario and east to Canada’s Maritime Provinces. Black ash typically grows in wet areas, near streams or poorly drained, often seasonally flooded areas. St. Louis, Itasca, and Koochiching Counties boast the thickest ash forests in Minnesota—each county has more than 60 million ash trees.

“Ash is a minor component of a lot of our native forest communities,” Minnesota DNR forest

ecologist John Almendinger told Wilderness News. “It’s not like you’re going to drive up to your cabin and see 20 miles of dead ash trees. These communities on the average occur in fairly small inclusions in other forest types.”

“[The damage] is going to be very dispersed through the forests,” he continued. “There’s no huge landform or place where it’s almost all ash trees. So it’s going to be holes here and there in the forest canopy where ash trees are gone. If you add up the acreage of all those little holes, it’s about a half-million acres.”

The Minnesota DNR identifies two ash-dominated forest types in its native forest classification system—the Northern Wet Ash Swamp and the Northern Very Wet Ash Swamp.

“These are places on the land where, if this critter is as virulent as advertised, all the trees are going to die,” Almendinger predicted. “In one of those communities, the wet ash swamp, other trees will come in, almost certainly. The very wet ash swamps, to be honest, right now we can’t generate ash on them very successfully.”

Almendinger expects balsam poplar to populate the wet ash swamps likely to be decimated by emerald ash borer. In very wet locales—places with standing water in spring and summer, rather than seasonally—he expects alder or cattail swamps to replace ash.

“Ash has been suffering from natural decline in northern Minnesota in the past few years,” Almendinger said, attributed to climatic and environmental factors. “And, it’s all in that one community – the very wet ash swamps. My best guess as an ecologist is that, whether its emerald ash borer or you cut them all down with a chain-saw, it’s not going to be forest anymore.”

Forests Without Ash, Swamps without Forests?

The advent of emerald ash borer offers a lot to ponder. Almendinger wonders, on one hand, if the insect will survive Minnesota’s harsh winters. “They haven’t lived through a Minnesota winter yet,” he noted. “I know we’ve got global warming and all this other stuff, but you know what, Minnesota winter is pretty nasty. And if these things have to over-winter as adults, they may not make it.”

Noting that the spread of emerald ash borer seems more aggressive to the east, west, and south, he also wonders if the placement of black ash within a boreal matrix of tree species will slow the insect. He wonders, too, if some part of the black ash genome might offer resistance—just as some elm trees resist Dutch elm disease. Almendinger also questions what effect the potential loss of a quarter-million acres of very wet ash forest will have on biodiversity.

“A great deal of the biodiversity in northern forests really focuses on these wet ash holes,” he noted. “Almost all the amphibians in upland habits are linked to them. All these ash swamps in the spring are a constant succession of frogs. You can take a quart jar out there in the spring and get half-water, half-polliwogs. There may be some species that will totally abandon [the sites], if the trees aren’t there.”

Only time will tell just how devastating emerald ash borers will be in the northern forest. Likewise, what effects the projected loss of ash trees will have on the ecology of the small wetlands where ash now make their home is something only the advance of time—and a small green insect—can answer.

Read more in Wilderness News Summer 2009