[Part I of this story appeared in the Fall 2003 issue of Wilderness News]

The Big Resorts – Basswood Lake, Crooked Lake

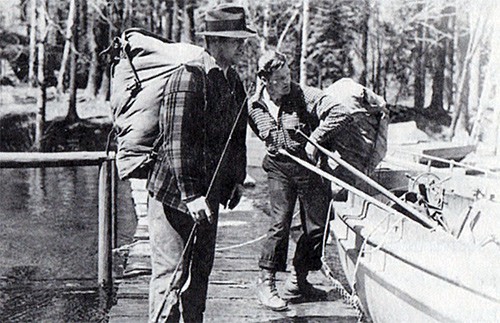

Throughout the 1930s, tourism spread rapidly into the roadless areas in the east from Grand Marais, and in the west from Ely, where Basswood Lake became a primary destination. It was reachable by seaplane, boat, or by a combination of rough roads and motorized portage. Basswood offered easy access to fishing on both sides of the Canada/MN border, and a network of islands and secluded bays. By the late 1950s there were more than 20 resorts on Basswood alone, and at least two successful resorts thrived on nearby Crooked Lake, overlooking the spectacular Curtain Falls. The Curtain Falls Fishing Camp was reached only by seaplane, and is rumored to have had a slot machine and a popular bar in the main lodge. One of the largest resorts of the era was the Basswood Lodge & Wilderness Outfitters. Begun in 1921 as a rustic fishing camp, not only did the lodge provide complete outfitting, it boasted one of the most majestic hand-crafted log lodges, accommodations for over 100 guests, and two seaplane flights daily into Ely. To further appeal to tourists, a few lodge owners installed motorized portages between lakes, facilitating larger groups and fishing boats, including 4-Mile Portage, connecting Ely to Basswood.

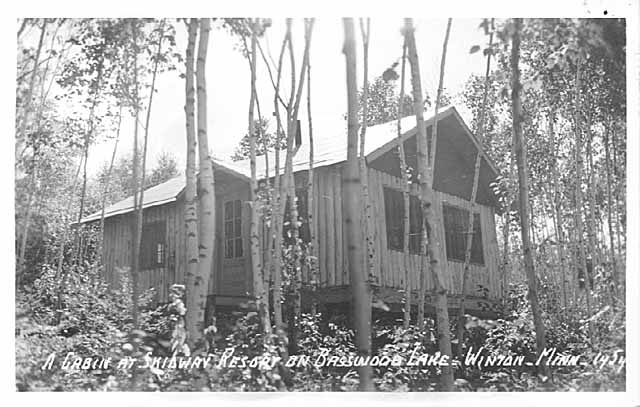

Other popular destinations on Basswood Lake included the Pipestone Falls Lodge, Skidway Borderline Lodge, Pinecliff Lodge, the Johnson Bros. Fishing Camp, and Evergreen Lodge.

They ranged from single-cabin establishments to multi-cabin resorts. In addition to numerous private cabins and resorts, several ‘corporate retreats’ were built as well. The lake bustled with activity from June to September, both on shore and on the water.

Remembering the Lodges

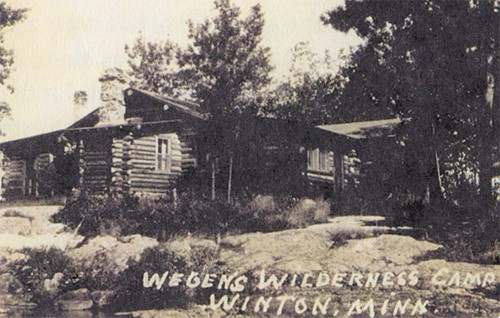

Doris Wegen Patton grew up exploring the Boundary Waters during summers spent at ‘Wegen’s Wilderness Camp’ on Newton Lake; begun by her parents in 1924. She remembers entertaining visitors from across the country and cherishes memories of living without telephones or running water, making ice cream with ice stored in sawdust from the previous winter, waiting eagerly for the boats full of guests, mail, library books, and supplies, and trading with Native Americans arriving by birch-bark canoe. The family eventually sold the camp and built a private home on Basswood, joining a close-knit community on the lake.

Closing ‘The Nation’s Playground’

After WWII, with a growing interest in preservation, conservationists put increased pressure on

Congress to protect certain wilderness areas– stressing that without intervention, the northwoods would be decimated by logging and commercial establishments. The conservationists emphasized preserving the natural state of the area, its land, waters, animal life, and solitude — which meant eliminating roads, airplanes, and eventually, motorized travel of all kinds. Congress passed the Thye-Blatnik Act in 1948, appropriating funds to buy resorts and private lands within the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. The Act was extended and funded two more times, in 1956 and 1961. The executive order, signed by President Truman in 1949, prohibited airplane landings within the BWCA. This order was enforced by U.S. Marshalls, thus closing all seaplane operations that served the lodges. The Izaak Walton League established private endowment funds to acquire 14 strategic properties, enlarging the properties already protected by the government. Further appropriations would follow, and in 1964, with the passage of the Wilderness Act, the area was declared free of roads, logging, motorized travel, and commercial businesses. As a result, all resorts and private cabins within the Act’s boundaries were purchased, condemned, or closed by the government. By the late 1960s, over 40 resorts and over 90 private homes had been purchased. The newly defined region would be officially designated as the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness later in 1978.

What Remains Today

As plans were drawn for the new wilderness area, the boundaries determined which resorts would close. Lodges that were on major roads or close to the towns of Ely, Winton, and Grand Marais were not within the new wilderness area, and spared from removal. One of the oldest, the Burntside Lodge, built in 1913, is still entertaining guests today, as are several other resorts from this period along the Echo Trail, Gunflint Trail, and Fernberg Corridor, including the Clearwater Lodge, the Nor’Wester Lodge, and the Gunflint Lodge.

Basswood Lake saw the greatest change. Over 20 resorts and numerous summer residences were closed or removed. The prominent main building at Basswood Lodge was purchased by the government in 1964, dismantled, and sold to a local entrepreneur. He hauled the pieces across the ice, making it the centerpiece of a new resort, Snowbank Lodge. Then, in 1978, with the official designation of the BWCAW, part of Snowbank Lake was declared within the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. The government purchased the same lodge for a second time, and planned to destroy it. In 1985, it was purchased for $1.00 by Burnett County, removed, and rebuilt. The building is now the visitor center at Forts Folle Avoine Historical Park, in Danbury, Wisconsin.

Other remnants live on as well. The original Wilderness Outfitters that began at Basswood Lodge still operates today out of Ely, and some of the dislocated businesses moved to Lac La Croix, Crane Lake, and other lakes just outside of the BWCAW.

Of those buildings that were sold, portions of the Pinecliff Lodge and the Evergreen Lodge were purchased by Wilderness Canoe Base (then run by the Plymouth Youth Center in Minneapolis) and moved to their camp on the Seagull Lake chain. Though one of the main buildings was later destroyed by fire, many of the cabins are still in use, sheltering campers amidst the wilderness experience. The resorts on Crooked Lake and other remote lakes were made inaccessible by the seaplane ban, and either removed or destroyed. Former residents recall hauling cabins out onto the ice and burning them down on cold winter nights.

Today, as you paddle the old route from Basswood to Curtain Falls, few would guess what a busy resort area this once was – nature has quickly reclaimed its shores, canoes have replaced fishing excursions, and an old stone foundation, a few postcards, and many fond memories are all that remain.

By Kari Finkler, Wilderness News Contributor

This article appeared in Wilderness News Spring 2004