By Alissa Johnson

In 1964, Fred Winston, Wilderness News editor, received an inquiry following the newsletter’s inaugural publication: “I can see that there are many sides to Minnesota’s wilderness problem. But which side are you on? What are you trying to prove?”

It was a reasonable question: wilderness had indeed become a problem in Minnesota. The inclusion of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area in the Wilderness Act of 1964 was so controversial that it was included with exceptions. Whereas the Act halted commercial development in the fifty-three other wilderness areas it created, development in the BWCA was left to the Secretary of Agriculture and a special committee to determine—emotional and contentious public meetings and public debate ensued. In such a climate, the idea of unbiased coverage from an organization vested in the region’s wilderness character was almost unfathomable; surely there was an ulterior motive.

There was, it turned out. But not the kind this reader might have expected. The editor responded to this “rather pointed, but natural, question” in the next edition: “The only way to arrive at an equitable solution of any problem is first to listen to all facts and all opinions of all sides. This, at least, is what we are trying to prove.” It was the conclusion to a half-page article that thoroughly outlined the history of the Quetico Superior Foundation and the editorial position of Wilderness News. This complete attention to detail and commitment to unbiased news coverage would come to characterize the publication—and would hardly come as a surprise to anyone familiar with the newsletter’s editor and sole writer, Fred Winston.

Fred was a mainstay of Wilderness News and the Quetico Superior Foundation, of which he served as a long-time president. How long? In his own words, “a long time.” One might expect a man so careful about detail to immediately recall the exact number of years he served at the organization’s helm, but there is one quality that Fred Winston possesses in excess of thoroughness: humility. For Fred, his tenure at QSF is less something to laud and simply a matter of fact.

To many, Fred’s involvement in the Quetico Superior Foundation might appear to be a natural succession in family history. During the 1940s, Fred’s father, the late Frederick Winston, was part of the “group of outdoor-minded Minnesotans,” as Fred called them in his 1964 article, to create “this tax-exempt, non-profit organization . . . for the general purpose of advancing science and education [in] that part of America defined by the watersheds of the Rainy and Pigeon rivers of the United States and Canada. In Canada the area embraces Ontario’s Quetico Provinical Park; in the U.S. Minnesota’s Superior National Forest.” It was a natural fit for Fred’s father, whose involvement in regional developments began during the 1920s; he joined activist Ernest Oberholtzer and the Quetico Superior Council in preventing the damming of the Rainy Lake watershed and working to create an international peace park in the border lakes region. (As Fred grew up, well-known and outspoken wilderness advocates like Oberholtzer and northwoods writer and activist Sigurd Olson were regular fixtures in family life). Oberholtzer even visited at Christmas, and the family made visits to his retreat on Mallard Island.

But for the younger Fred, taking the helm at the Quetico Superior Foundation and editing Wilderness News was not about family legacy or grand purpose. Today, reflecting back, he attributes his involvement to living in Minnesota, rather than moving away as his siblings did—as he puts it today, “the fact that I was here”—and a passion for canoeing that grew throughout his adult life. To Fred, it was simply a natural byproduct of engaging with the world around him. Or rather, engaging in the world around him with his family. For Fred is quite matter-of-fact when he attributes his continued interest in canoeing and the border lakes region to the fact that his wife, Eleanor, was passionate about canoeing as well.

Eleanor grew up hiking and horseback riding through the woods of Long Lake, Minnesota, just down the road from where the couple lives now. She loved noticing all the changes in the woods from season to season and year to year, including “every little tree that falls.” According to Eleanor, her first canoe trip in the Boundary Waters opened up a whole new world to explore. She and Fred returned annually, taking their kids from the time they were very young, and over the years continuing to visit family friends of old, like Frank Hubacheck, one of the Quetico Superior Council’s original members, at his place on Basswood Lake, stopping by Sigurd Olson’s writing shack after canoe trips, and visiting Mallard Island. The couple continues to

paddle the BWCAW nearly every September, and it is this family tradition that both Eleanor and Fred credit for their ongoing passion for the issues impacting the region.

“Because we continued [canoeing] it helped us stay interested . . . . If you’re not actively using the [wilderness] it’s harder to stay involved.” And issues there have been. Fred’s tenure at QSF and writing for Wilderness News gave him the opportunity to cover everything from the fallout from the 1964 Wilderness Act to the mining ban debates during the 1970s and the eventual passage of the Boundary Waters Wilderness Act of 1978 to the 1999 blowdown. Though he speaks lightly of his role, he strove to present all sides of a story and remain neutral, staying true to the words he wrote in 1964:

“It is the management of this unique strip of geography . . . which is now causing so much sound and fury. Some say it should be managed more intensely. Some say it should not be managed at all. Some favor logging and mining there. Others would permit more resorts, more roads, more mechanized transportation. Still others would block off the region to all but the paddling canoeist, the plodding hiker. We believe these voices crying in the wilderness should all have a fair hearing.”

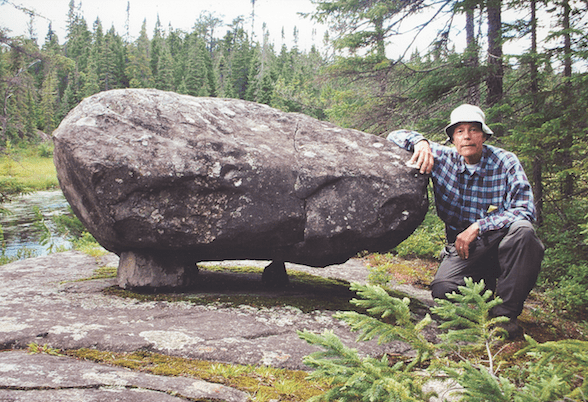

Like most interested groups, the Foundation wants to hear the testimony and weigh the evidence before passing judgment. He carried black and white film with him whenever he traveled to gather photographs for the newsletter, and through his careful attention to detail created the foundation for the publication that is Wilderness News today. Yet nowhere did Fred’s name appear in a byline, other than the masthead, and nowhere did he insert his opinion, other than, perhaps, to assert that Wilderness News should not have an opinion as his article did so eloquently. He strove to provide a trustworthy voice that shed light on the issues facing a region he happened to visit and care deeply about. To appreciate his example and imagine the possibilities if everyone stayed so active in the places they visited—well, that is a refreshing point indeed.

Read more in Wilderness News Summer 2009