By Alissa Johnson

Meet the Wolf Lake Citizen’s Monitoring Group. Together with the Forest Service, they’re proving that private landowners and the government can work together to care for land.

The relationship between the Wolf Lake Citizen’s Monitoring Group and the U.S. Forest Service started in an all too familiar way: in court. In 1997, the Forest Service issued a permit to build a four and half mile road into a stretch of forest on the edge of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness without conducting an Environmental Assessment or an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). Area landowners gathered more than 100 signatures in protest, beginning a decade of challenges that ended up in court on more than one occasion. And it might have continued that way if a new district ranger hadn’t suggested an alternative in 2007.

The Wolf Lake citizen’s group had just contested the latest EIS for the Echo Trail. According to Doug Wallace, who spearheads the monitoring group with his wife Peggy, the EIS gave four reasons that the inventoried roadless area did not qualify for elevated protection: it was regularly used by snowmobilers; it had recently been logged; there was high potential for future development by other ownership; and people used it to reach private lands. Based on research the homeowners had conducted themselves, they knew each claim to be false. But district ranger Nancy Larsen did something unusual: she asked them to withdraw their contention, and in exchange, promised the Forest Service would reexamine the record. The group agreed, and in the end the Forest Service amended the EIS and the Forest’s management plan to side with the landowners. Then Larsen had another idea.

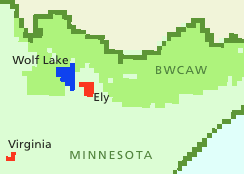

“She said, ‘You know more about this area than our staff, so why don’t you consider the possibility of doing a demonstration project of what a citizen’s monitoring group could do?’ ” says Wallace. The group gave Larsen’s suggestion a shot, and in the nearly five years since the landowners have taken on an ever-expanding role in monitoring the Wolf Lake roadless area, adjacent to the Trout Lake area of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW).

A group of about 18 families monitor plant and animal species as well as human use of the area. They provide the Forest Service with an annual report, allowing the agency to form a clearer picture of what’s happening across the forest. The group’s monitoring has already confirmed the presence of invasive earth worms, which eat through the duff on the forest floor, and they have confirmed the presence of about 13 bird species that are “species of special need.” Among them is the Canada Warbler, which is listed as a bird of concern by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

“The outcomes are improved data for the Superior National Forest, but this effort also provides a good two-way communication between the Forest Service and landowners,” says Bruce Anderson, Superior Forest Monitoring Coordinator. He works with the group to select annual training and monitoring projects.

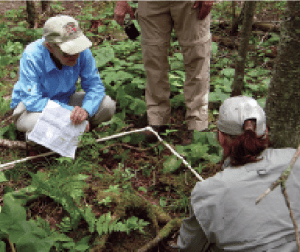

The Forest Service has provided the group with training on surveying techniques, forest classification, and identification of basic plant, aquatic and terrestrial species. Recently, the monitoring group also joined a climate change study, working with the lead scientist to collect data on a plot in the Wolf Lake roadless area. The group recorded dead and down timber, the size of remaining timber, plant life, regeneration of the forest floor and a variety of other data that will, over time, form a picture of how the forest is changing over time. Looking ahead to next summer, Anderson says, the Forest Service and the monitoring group are considering a partnership with a rare bird expert. But as the group’s role continues to evolve every year, it’s no longer limited to simply monitoring.

“They are also looking at helping us create more recreational opportunities for the public,” says Tim Sexton, Larsen’s successor. “One of the projects we’re working on now, in infancy stage, is a birding trail…. They have offered to do most of the work associated with creating and maintaining the trail as well as develop the informational media that would support it.”

The idea for the trail—proposed at the end of the portage into Wolf Lake—came from birders, Alan and Karen Orr. They got involved with the monitoring group after Wallace noticed them walking around with binoculars. He asked them to help with bird monitoring, and initially, they performed line transect surveys. By walking an established line and recording bird sightings by sight and sound, they established a formal record of the species present in the area.

“We’re in the process now of establishing point count observations, which go into a specific locale on a frequency two or three times a year over a period of years,” says Allen Orr. “We simply stay in that area for a specified time and record what we see and hear, and that has more value for the Forest Service, and it also has value in terms of being able to apply statistical analysis.”

Their data has confirmed the region as one of rich avian diversity, and the Orrs suggested a nature trail as a way to draw people to the region. Orr believes recreational birding could have some economic impact on the area.

“There are indications that birding might have some economic impact on the state of Minnesota, but it needs to be pushed up the hill. Of course, that’s not my goal. We’re involved with the group because we enjoy birding,” says Orr. It’s that passion, he believes, that drives involvement in groups like the Wolf Lake Citizen’s Monitoring Group.

“It stems from a long history of citizen involvement, citizen conservationists who have an interest in nature and who want to assist agencies, government or private, in terms of helping preserve environmental conditions in a particular locale.”

But what Orr sees as tradition, others see as unique. Anderson has seen partnerships between the agency and environmental organizations, and collaborative groups that include several entities. But the direct relationship between landowners and the agency is something else altogether.

“It’s a two-way street right now, there is information going both ways, what we contribute is training labor and what the Wolf Lake group contributes is labor to do inventory and monitoring,” Anderson says. Both he and Sexton see a great deal of value in the partnership.

This article appeared in the Summer 2012 edition of Wilderness News >