The Pagami Creek Fire burns 93,000 acres, blazes into the largest naturally occurring wildfire in a century.

By Charlie Mahler

In the heat of summer, with the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness peppered with campers, U.S. Forest Service officials charged with managing the million-acre wilderness and the surrounding Superior National Forest faced a decision. A lightning-caused fire was burning to the southwest of Lakes One, Two, and Three near Ely, MN. Should they put it out or should they allow it to burn?

On the one hand, the forest in the path of the fire was ready for burning. The last major fire in the area had flamed nearly a century before and the regrowth of trees after much of the area was logged in the middle of the last century provided a rich source of fuels. In an ecosystem where wildfire has always played a vital role in forest succession and health, the burgeoning fire could be seen as a welcome event.

On the other hand, the fire had the potential to char acres of the forest decorating some of the most popular camping destinations in the BWCAW and close down the busy ‘Number Lakes’ travel corridor during the height of the canoe/camping season. If the fire ran, there was also the possibility that it would leave the wilderness area and threaten property and lives. Or, the fire might reach the trees toppled in the July 4, 1999 blowdown, creating a conflagration in the wilderness that could spread into the populated areas along the Gunflint Trail.

If the needs of the forest were for a fire, the wants of the people argued for fire suppression.

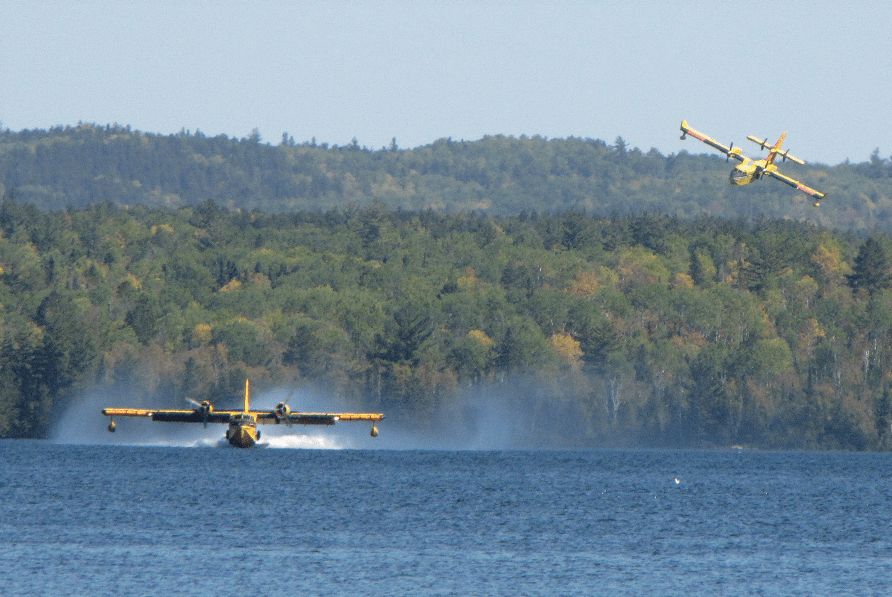

In the end, the Forest Service chose to put out that fire – the Turtle Lake Fire of 2006. Aircraft doused its flames with water, firefighters met it on the ground, and the blaze was contained to just 2,085 acres. The fire only blackened the area east of Turtle Lake and the fingers of land between Clearwater, Pietro, and Gull Lakes.

Computer projections of what the fire might have done had it not been stopped in its tracks suggest

it would have burned north to the shore of Lake Three, east to Pose and Fallen Arch lakes on the Pow Wow Hiking Trail, south to the Isabella River and Quadga Lake near the wilderness boundary, and west to the shores of Bald Eagle Lake.

In 2006, fire suppression around Turtle Lake kept the forest green, kept the Number Lakes route open for the season, and assured that neither lives nor property were lost to those flames. South of Lakes One, Two, and Three, however, and south of a little waterway flowing out of Clearwater Lake, listed on maps as Pagami Creek, the forest fuels that might have burned in 2006 remained in place.

Five summers later, a lightning strike to one of the trees lining Pagami Creek would initiate what ultimately grew into the largest wildfire in Minnesota in more than a century – one that grew, in part, thanks to the fuel-rich forests that remained unburned in the summer of 2006.

For a fire that ended up burning nearly 93,000 acres of forest to the south and east of its ignition point, the Pagami Creek Fire initially prompted concern over what lay to its north, and, that, only after the fire burned slowly and largely in place more than a week. Soil conditions and forecast weather suggested to Forest Service officials that the fire, like many in 2011, posed little threat to the wilderness.

“All of those factors pretty much told us that there wasn’t any indication that this fire was going to get real large,” Mark Van Every, the Superior National Forest’s Kawishiwi District Ranger, told Wilderness News in October. “It showed that the fire would grow over time, but not that it would get anywhere close to what it did. We had a number of fires that we handled similarly to this one, starting as early as May and June, that we managed as a natural fire.”

On August 26, however, as conditions on the ground got drier and predicted rains failed to fall, the fire made a run that expanded its footprint to the southeast. Concern for what lay to the north prompted Van Every and the Forest Service to mobilize a team to contain the fire.

“From August 26, when the fire made its first run to 130 acres, we took immediate action to suppress the fire and had been doing so ever since,” Van Every emphasized.

Pagami Creek, located southeast of the South Kawishiwi River, is a mere three miles, as the crow flies, from the Fernberg Trail which connects Ely with a constellation of BWCAW entry points on the west side of the wilderness and which is populated with resorts and vacation homes. Concern mounted that prevailing autumn winds could drive the fire north, putting property and lives at risk.

On Labor Day weekend, September 3, 4, and 5, firefighters took the bold – and ultimately controversial step – of burning approximately 2,000 acres of forest mostly to the northeast of the Pagami Creek ignition point, in an effort to protect the Fernberg Road corridor. Using planes that dropped jellied gasoline on the wilderness forest, the ‘burn out’ operation torched the forest southwest of Lake One and west of Lake Two.

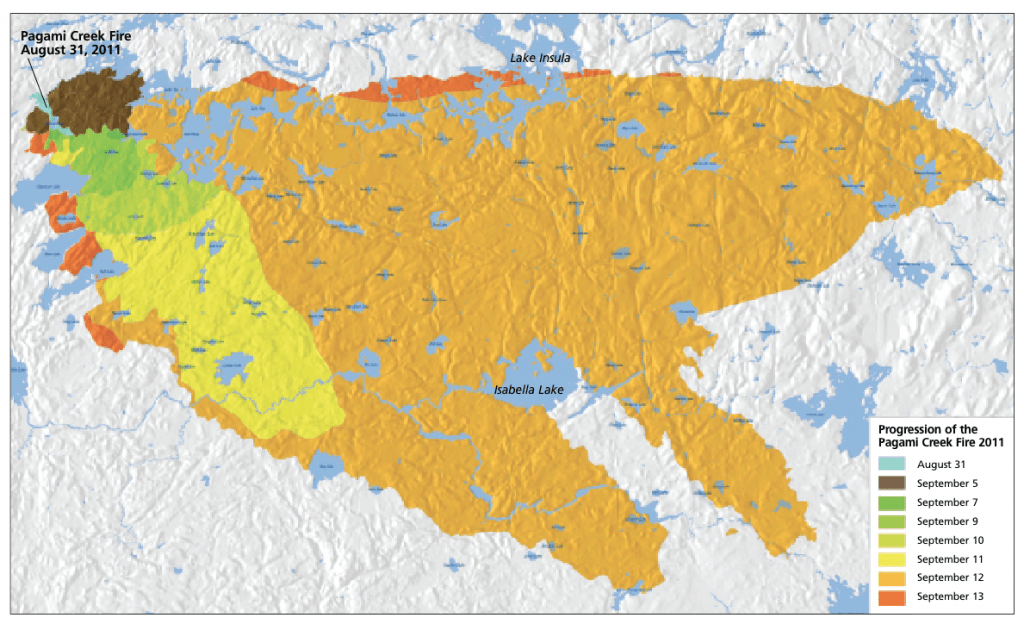

On September 9, however, from the southern edge of the original fire and the burn out operation, the fire nearly doubled in size, pushing southeast of the paddle-and-portage route between Clearwater Lake and Lake Two. The next day the fire front pushed further south, consuming nearly 4,000 acres as it blazed through the forest between Lake Three and Pietro Lake.

Van Every acknowledges that the burn-out operation to protect against a northward run by the fire may have contributed to the southern advance.

“We’re looking at a lot of that,” he said in October. There’s probably no question that some of the fire spread that came [south] came out of [the burn-out area], but as near as we can tell most of it came out of this original 130-acre burn.”

The southern advances on September 9 and 10 consumed forest that was spared in 2006 when the officials decided to snuff out the Turtle Lake Fire. When the flames of the Pagami Creek Fire met the forest burned in 2006 – in the fingers of land between Clearwater, Pietro, and Gull Lakes – the fire was stopped dead.

Fire suppression five years ago helped set the stage for the Pagami Creek Fire’s two signature days – September 11 and 12 – when the fire tore south and then exploded east, torching a grand total of 92,682 acres of forest inside and outside the wilderness, threatening lives and property, and making Pagami Creek synonymous with a raging wildfire rather than a sleepy little creek meandering through the Boundary Waters.

September 10th

When the sun set on the northwoods on Saturday, September 10, the Pagami Creek Fire had left a black footprint of charred forest from Lake One in the north to an arc running from Pietro Lake to Horseshoe Lake in the south. Twenty-two days into the fire, 4,500 acres had burned, and an active fire front on the south edge of the fire had firefighters increasingly nervous.

The fire had burned 1,750 acres during the day on that Saturday. Surface moisture values, which firefighters use to forecast the likelihood of fire spread, were nearing the peak of a month-long climb from levels below the seasonal average (and well below those needed to propagate a wildfire) to near-record levels for early fall.

On the first of what would be the two defining days for the Pagami Creek Fire, the fire front burned a tongue of forest for six miles to the south, advancing from north of Gull Lake, over the western section of the Pow Wow Hiking Trails, through Quadga Lake, across the Isabella River, to within a mile of the wilderness’ southern boundary.

The flames consumed more than 10,000 acres, nearly quadrupling the size of the fire in a single day. Disconcertingly, the fire’s dash to the south opened wide fire fronts to the east and west, ominous developments, if wind direction changed. Firefighters continued attempts to clear endangered people from within a widening circle of forest.

“Every day we would sit and draw a line around the fire and say, how far do we think it could get tomorrow, based on the predicted weather, the current fire indicators, and all that,” Van Every recalled. “We’d double that, and then go out that far and move people out of the way. [After September 11], we thought it might, possibly, make Insula Lake in two days. It did it in less than two hours.”

September 12th

Fanned by strong southwesterly winds, on Monday morning, September 12, the newly-opened eastern front to the fire sprinted to the east at a pace unprecedented for a Boundary Waters fire, according to Van Every. Pushing from a fireline that extended from below Horseshoe Lake to Diana Lake on the Pow Wow Hiking Trail, the front advanced five miles in one hour. Landsat satellite imagery taken at 11:45 a.m. that day showed winds blowing huge orange flames and smoke toward the northeast. At noon, six wilderness rangers, who were clearing campers from Insula Lake, were forced to deploy their fire shelters as hot embers rained on them.

“No one ever expected the fire to go that far in a single day, let alone as fast as it did in a single day,” Van Every said. “We’ve never seen that happen before, ever. The Ham Lake Fire and the Cavity Lake Fire, which moved pretty rapidly, I think the most that either of those fires moved in a single day was five miles. This was 16 miles in basically a matter of hours.”

The raging fire caused smoke to billow high into the atmosphere, producing its own weather that included thunder, lightning, hail, and high winds. Residents of homes north of Isabella were evacuated, while residents of Isabella proper were told to be ready to evacuate on short notice. By the end of that fateful day, the footprint of the fire had marked its chicken-shaped burn on the landscape.

The area blackened on September 12 ran on a farily straight line from above Hudson Lake, across half of Insula Lake, and to the southern shore of Lake Polly to the north. Its southeastern edge ran from Lake Polly, through Kawasachong Lake to Ferne Lake. Two long legs of burned area scarred the forest starting at Isabella Lake and running to the Island River, west of Perent Lake in one case, and to Section 29 Lake in the other. From Section 29 Lake, the southwestern edge of the burn ran south of the Island River to Bog Lake and to the west of Quadga, Superstition, and Phospor Lakes.

More than 80% of the fire’s total acreage burned on September 12 alone. A total of 114 campsites were affected by the fire, 51 of which received “severe” effects, according to the Forest Service. Van Every was quick to note that only 5% of the campsites in the wilderness were impacted by the fire. Still, 20% of the campsites in the Lake One to Insula Lake travel corridor did receive severe damage. Recreational travel in the area remains closed until spring.

The frontiers of the fire advanced only slightly after September 12, thanks to helpful weather and the firefighting efforts that mobilized nearly 900 firefighters to the area at the height of the effort and ultimately ended up costing more than $22 million.

In the weeks after September 12, as cooler, wetter autumn weather came to the Boundary Waters region, firefighters slowly tightened the fire containment noose around the Pagami Creek Fire. By September 19, the fire was described as 23% contained. By October 2, the fire was deemed 71% contained, and on October 22, as firefighting efforts wound down, the fire was deemed 94% contained.

In the aftermath of the fire, critics have questioned Forest Service decision-making at critical stages in the incident. Should the fire have been snuffed immediately? Did the “burn-out” operation, designed to protect the Fernberg Road corridor to the north of the original fire, contribute significantly to the ultimate advance of the fire to the south? Why were fire behavior projections so far off the mark? Was the balance between the ecological and human values related to the fire tipped in the wrong direction?

“Do we have it wrong, do we need to put every fire out?” Van Every asked himself during the interview for this story. He pointed to a map on his computer screen. “This is the Turtle Lake Fire; we stopped it right here. We used aircraft, we used firefighters. Based on the actual weather we had during that 10-day period in 2006, this is what that fire would have done if we hadn’t stopped it.”

Van Every’s map of the projected fire showed a burned area running through the land between Clearwater, Pietro, and Gull Lakes, up to Lake Three and down to Bald Eagle Lake and the Isabella River in the south, and spreading west into the Pow Wow Hiking Trail country to Pose Lake – the forest where the Pagami Creek Fire began to run in early September of 2011.

“It would have provided an effective barrier to this fire,” Van Every contended. “So the decisions that we make today – not that that was a wrong decision in 2006 – affect what happens in the future. If we had put Pagami Creek out, sooner or later we’d have had a large fire.”

“Our whole reason for allowing fires to burn in the wilderness,” Van Every continued, “is to create that mosaic pattern so, if we did get a fire, there are some things for that fire to work around, and there’s the opportunity for us to have some suppression where needed.”

This article appeared in Wilderness News Fall-Winter 2011 >