PolyMet Mining Corp. has been given the green light to move into the final phase of approval for its proposed project in the St. Louis River watershed. The state’s Department of Natural Resources and Governor, in charge of determining its fate, declared the proposal’s Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) “adequate” today, and said that the company can now apply for the permits it would need to mine.

The decision is a significant moment in the proposal’s long, difficult march, which began 12 years ago. The FEIS will guide upcoming decisions about whether or not the mine can legally and safely operate.

“The environmental review process is about describing the potential environmental effects of the proposed NorthMet project,” DNR commissioner Tom Landwehr said. “We are confident this document has thoroughly examined the important environmental topics and has addressed them.”

As the first potential copper-nickel mine in Minnesota, presenting much different challenges than the state’s traditional iron mining, the project has received intense, and often critical, scrutiny. While the waste from iron mining is relatively benign, copper ore is full of chemicals that cause toxic drainage. The environmental review process is intended to determine if a proposal can meet state standards.

Since 2004, Landwehr told a press conference today that government staff and contractors have put 90,000 hours of work has been put into the project. That about the same as one person working a full-time job for 45 years. He said it is the largest environmental review process ever undertaken by the agency. (PolyMet reimburses the state for all costs.)

“The state’s decision validates both the Final EIS and the exhaustive process supporting the final document. This is an historic event for Minnesota, the Iron Range, and for PolyMet, clearing the path for permit applications required for construction,” stated Jon Cherry, the company’s president and CEO.

Associated Press reporter Steve Karnowski provided a thorough article tracing the history of the environmental review. The company started the process in 2004 and released a draft in 2009 that was blasted by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and issued a new 3,500-page version in 2013.

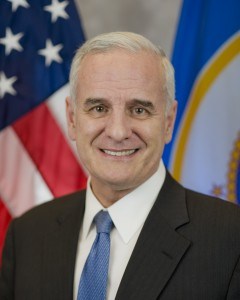

Governor Dayton said he remains “genuinely undecided” on the project at a project. “I don’t know what the permitting process is going to determine. I don’t know what changes the company is willing to make to satisfy those concerns.”

The permitting phase has long been when the company and regulators have said big issues like financial assurance will be determined. Opponents asked for detailed information about this “damage deposit” during the environmental review phase, but were rebuffed.

Financial assurance promises to be one of the most contentious decisions ahead. While everyone seems to agree that ensuring taxpayers aren’t stuck with clean-up costs is not acceptable, big questions remain about how much, when, and in what form such fund would be required. The amount will also change over time – from if and when permits are issued and PolyMet officially inherits legacy pollution at the old LTV site is has acquired, to when the first ground is broken, and through the life of the mine’s expansion and closure.

Other issues, like the wastewater treatment that is expected to be necessary for centuries, will also be examined in much closer detail now.

The company needs more than 20 different permits to begin operating, Landwehr said. Sixteen of those are from state agencies, including a permit to mine and dam safety permit from the DNR and water quality and air quality permits from the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency.

The permit to mine process evaluates many details of the proposed mine plan, including financial assurance. Financial assurance is the money a company must set aside to ensure essential environmental protections are funded in the event the company is unable or unwilling to implement those measures.

The completion of environmental review could also trigger legal challenges from opponents. Landwehr said lawsuits are “entirely possible,” while Dayton said he expected “whichever side is not satisfied with the outcome will sue.”

Because the state has decided that PolyMet can meet its standards, and because decisions to issue permits are based on those same standards, Landwher pulled out what he called an old analogy to explain why declaring the FEIS “adequate” is not the same thing as approving the project.

“The EIS is not unlike if you’re going to buy a house. You have to decide what neighborhood, how much can I afford, pull in contractor to make sure its up to standards. That is still not a decision,” he said. “Then you have to apply for mortgage, figuring out moving, et cetera.”

Landwehr said PolyMet has begun working on some of its permit applications. Until they are received and reviewed, there is no way to predict how long it will take to consider them.