Quetico Provincial Park, which adjoins the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness across the Canadian border, has been designated an International Dark Sky Park. The announcement this week cited the canoe country’s absence of almost any light pollution.

The designation is part of a regional initiative coordinated by the Heart of the Continent Partnership to promote and protect the region’s cherished starry skies. It is bestowed by the International Dark Sky Association after an extensive application process.

“A starry sky free of light pollution is a source of wonder and inspiration for visitors to Quetico Provincial Park and an important part of the park’s natural environment,” said park superintendent Trevor Gibbs. “Receiving this designation from the IDA will help us to promote the preservation of night skies in our region and maintain the ecological integrity of the park.”

Quetico joins Voyageurs National Park and the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness in the recent Dark Sky designation. Voyageurs was designated in December 2020, and the BWCAW was the first last September. Two other Ontario Provincial Parks, Killarney and Lake Superior Provincial Parks, were designated Dark Sky parks by the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada in 2018.

Achieving Dark Sky Designation takes about two years, when applicants must measure the current quality of the night sky and commit to reducing light pollution. When designated, parks must implement a plan to convert their outdoor lighting to dark sky friendly fixtures, monitor night sky quality each year, and develop educational materials to promote dark sky protections. Dark Sky designation does not include any restrictions or regulations, but asks communities to consider night skies when making decisions about outdoor lighting. The city of Atikokan sent a letter fully supporting the application.

“We are very pleased with today’s announcement,” said Ruskin Hartley, executive director of the International Dark Sky Association. “Quetico Provincial Park is a great addition to the International Dark Sky Places Program. This designation underscores the park’s commitment to maintaining the integrity of the environment.”.

Starting in 2019, Quetico rangers began waking up in the middle of the short summer nights while in the park, and going outside to measure the darkness. It was a challenge, because half the sites required multi-day canoe trips to reach, and could only be visited during a new moon, the weather needed to cooperate with cloudless conditions, and complete darkness was only a few hours long each night.

But, at six sites spread across the park, the rangers found measurements that were about as purely dark as possible.

International Dark Sky Parks must have a darkness level measured at 21.2 magnitudes per square arc second or above. Twenty-two is as high as the scale goes. All of Quetico’s measurements significantly exceeded the threshold.

Also included was a map of light sources and pollution provided by an online service. It showed Quetico has few nearby sources of artificial light. “The majority of Quetico Provincial Park falls into the darkest range of Zenith Sky Brightness (21.9-22.0 magnitude/arc second squared) with a small intrusion from the town of Atikokan’s light dome on the north central edge of the park,” the application reported.

Quetico’s only developed campground and visitor center, Dawson Trail, is in the northeast part of the park, which was one of the areas least affected by light. As the most accessible site in the park for public events, it makes an excellent site for interpretive programs.

Surrounded by wilderness, Quetico has few immediate threats to its dark skies, park staff say. The application does not exclude the possibility of new industrial developments, such as mines, or the conversion of outdoor lighting to LED fixtures that are much worse sources of light pollution.

In the event of such a proposal, “the park would leverage its designation as a dark sky park, approach the development in question in order to educate and advocate for the minimization of light pollution, and seek the voluntary adoption of dark sky friendly measures.”

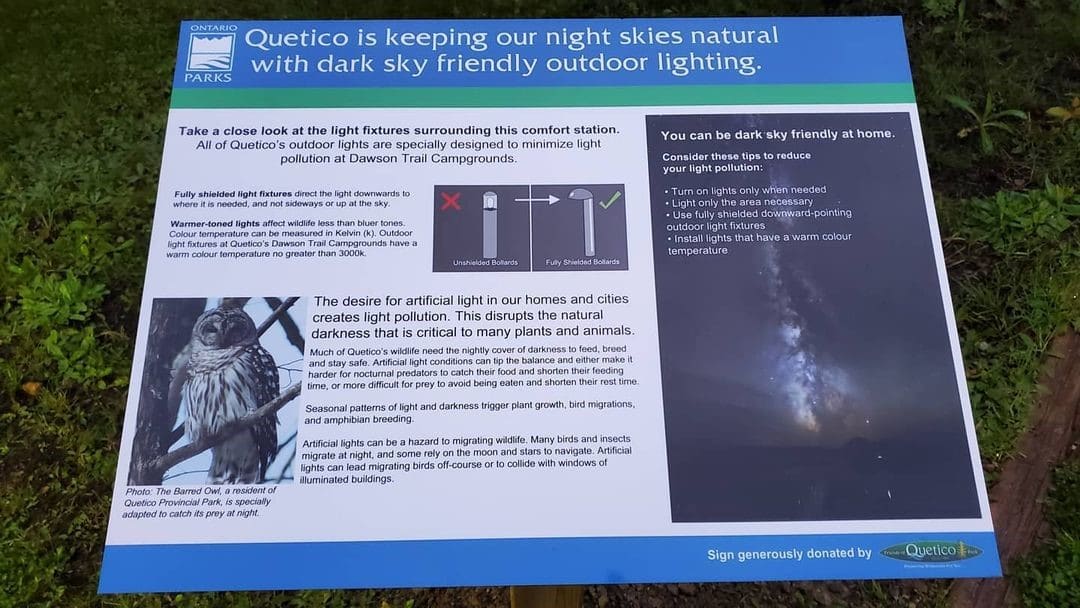

Quetico has already begun converting its lighting to night-sky fixtures, and plans to complete the process this year. The park has also installed signs explaining the lighting and the value of the region’s dark night skies.

The park will also start providing information to visitors about reducing their light impact while at the park. Last year, Quetico began a voluntary “dark sky friendly camper program” at Dawson Trail Campground, discouraging campers from leaving lights on at their sites overnight.

Quetico also plans to continue offering night sky programs every year, including working with the Lac La Croix First Nation on interpreting Anishinaabe star stories.

All of the efforts are part of trying to preserve an essential human experience: staring up in wonderment at a dark and starry night sky. In addition to amazing views of the Milky Way, the region is also known for the northern lights. People travel from around the world to see the aurora borealis.

Studies have shown in recent decades that light pollution negatively affects mental health and has other harmful effects on humans. But, almost all people on Earth live somewhere affected by artificial light. Many species of wildlife, from fireflies to bats to owls, depend on dark nights to survive.

At least in Quetico, this dark corner of the continent continues to provide a place to see natural night skies.

“When gazing skyward from one of Quetico’s campsites today, you can see a night sky similar in quality to what someone would have seen 100 or 1,000 years ago camped at that very same spot,” said superintendent Trevor Gibbs. “I hope that 100 years in the future, the same will hold true.”

More information:

- Quetico Provincial Park Awarded International Dark Sky Park Designation – IDA

- Quetico: an International Dark Sky Park – Ontario Parks

- Quetico Provincial Park (Canada) – Dark Sky Park