Marshall, Minnesota

(2000, 128 pages, $50.00-Hardcover)

Reviewed by David Pelly, author of six books about Canada’s Arctic, including Thelon: A River Sanctuary. Note: This review by David Pelly was originally published in Nastawgan, Spring 2001.

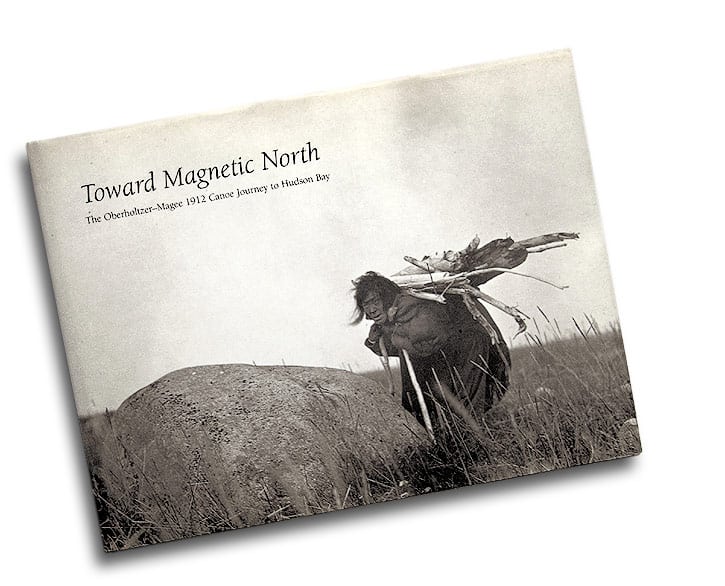

When a group of dedicated volunteers undertakes a project, and succeeds, the result typically rises above anything that simple commercial enterprise is capable of achieving. Such is the case with the book Toward Magnetic North, published by the Oberholtzer Foundation in Minnesota. This volume fairly sparkles.

In 1912, Ernest Oberholtzer and Billy Magee canoed from Lake Winnipeg north into the southern part of the Keewatin (now Kivalliq, Nunavut), east to Hudson Bay, and then south again (upriver) to Lake Winnipeg. The original plan was to follow J. B. Tyrrell’s route down the Kazan and out to Chesterfield Inlet on the Bay, but wisely the men decided to turn east when, in early August, they were only just crossing the 60th parallel. The journey of 3200 kilometers–some of it through country hitherto unmapped by white men–took them 133 days, and ended amid early November snow squalls. Oberholtzer was a 28-year-old Harvard graduate with a newly acquired penchant for wilderness travel by canoe. Magee, whose proper name was Titapeshwewitan, was a 50-year-old Ojibwa befriended by Oberholtzer three years earlier in the Rainy Lake district. For the people behind this book project, Oberholtzer is clearly a hero, his journey an epic. But it is implicitly evident that they are celebrating something more: his love for the land and dedication to wilderness preservation. According to the book, Oberholtzer was a founder of the Wilderness Society, and “the central figure in the seemingly endless struggle to preserve the wilderness areas on the Minnesota-Ontario border.” One gets the feeling that this life-long campaign had it roots in the 1912 journey.

The book offers several short and interesting essays, each from a different perspective, about the man himself, who died in 1977 at age 93. Brief excerpts from his trip journal are used to lay the foundation for the book’s main purpose, to present a selection of 70 of Oberholtzer’s black-and-white photographs, taken in 1912 with a large-format 3A Graflex camera weighing almost three kilograms. Some are better than others, of course, but taken together they provide a memorable sense of the man and the journey through unknown country. The most striking of all the images were captured in an Inuit camp at the mouth of the Thlewiaza River on Hudson Bay.

The forward to this book puts Oberholtzer in a league with Eric Morse and Sigurd Olson. Judging the man revealed in these pages, it seems apt, insofar as his love for the wilderness was obviously profound. One difference is that his legacy, as witnessed here, is photographic. As the book says: “Only a few years after Ober and Billy paddled to Hudson Bay, the north country became the domain of airplanes and gasoline engines. York boats became antique curiosities. Paddles were replaced by outboard motors, and dog teams gave way to snowmobiles. Ober’s photographs remind us that things change, but the wilderness he captured in them remains eternal.”

It is books such as this, which celebrate the wilderness, that give it even a fighting chance of being eternal.

This article appeared in Wilderness News Summer 2004