By Anne Queenan, Contributor

The sun casts its auburn spell on the red osier dogwood of a sedge meadow on County Road 7. In an open field, three white-tail deer gather by bales of hay partially covered in snow. As we make our way north, I am reminded how living in Minnesota can be a welcoming embrace of all of its seasons and natural wonders. During the months of December through early March, it’s an opportunity to witness the rhythms of wildlife burrowing, hunting and storing food between the frosted layers of a boreal terrain. This particular February day, we head to a bog that attracts many boreal winter birds to the area, particularly in Cook, Minnesota. Why do they come to the bog? How do they live here? What attracts birds to this habitat in northern Minnesota?

Definition of boreal (Merriam-Webster)

1: of, relating to, or located in northern regions boreal waters

2: of, relating to, or comprising the northern biotic area characterized especially by dominance of coniferous forests

Birding in Sax-Zim Bog

Our first stop is in the Sax-Zim Bog, a 300-square mile area consisting of a variety of habitat: bogs, fens, black spruce swamp, sedge meadows, open farm fields, private homes, county roads, the St. Louis and Whiteface Rivers, and upland deciduous forests. In a rural stretch adjacent to the small town of Meadowlands, birdwatchers and photographers from all parts of the world are returning in busses after a day in the field, including trips to Duluth and the North Shore of Lake Superior. They are here attending the thirteenth annual Sax-Zim Bog Winter Birding Festival.

We arrive at the Meadowlands Community Center just in time to join a room full of local neighbors taking delight in the tales of live raptors typically found in the bog. Three of these birds sit on the arm of an engaging presenter, Chris Tolman, from the Nature Connection of Bemidji, Minnesota. The faces of young children and adults alike light up as they learn about the predator habits of the Great Horned Owl, the Saw-whet Owl and the Rough-Legged Hawk.

Equipped with a checklist of local and visiting birds, a well-designed map of the area, and access to current sightings reported online, we find it’s easy to head out in search of these boreal birds who’ve been hanging out here at local feeders, landmarks and specific bogs. As many of these places are accessible from the road, it is not uncommon to find a few cars parked roadside with a line of birdwatchers nearby and their tripods mounted with scopes and long lenses. They’re hoping to get a glimpse of one of its year-long residents, the Great Gray Owl, who nests in the forested peatlands here, or perhaps another uncommon visitor, the Northern Hawk Owl.

Dusk is an active hour for these avian residents to hunt and we made our way to the Winterberry Bog as the sun was rapidly setting. Here we found new signage and a snow-trodden path through the forest. Our evening was brief, and without signs of the Boreal Owl who had been spotted earlier.

Little did we know that we would strike it rich with the Crabapple berries on a farm in Cook, Minnesota the very next day.

Since my last visit to the Sax-Zim Bog ten years ago, the number of people taking advantage of this opportunity to see boreal birds has increased substantially. As pleasing as it is to see more people learning about these birds and photographing them, another reality is that these birds have travelled long distances and may need to only focus on hunting, protecting their breeding territory and simply surviving. I was curious whether these same types of birds could be viewed in similar habitat in other parts of northern Minnesota. The answer is a resounding, “yes!”

Birding in Cook

To our good fortune, Julie Grahn, a resident of the area, spent the next morning with us in Cook, Minnesota. Through her guidance as a Master Naturalist, we were able to enjoy a scenic bog-like landscape on Johnson Road, enhanced with sunny, blue skies and fresh air. As the sole visitors, we listened and walked along the snowy road richly lined with dense spires of older black spruce, tamarack trees and occasional towering Jack Pines. Who was living deep within these trees and forested bogs?

Question: How would a reader know whether this would be a good winter for better birding success and expect to see certain birds coming south from Canada during the upcoming winter season?

Answer: One way is to follow Ron Pittaway’s Winter Finch Forecast. He’ll survey and gather data from naturalists and birders to see what the seed crops are like that year in Canada and make predictions based on this.

Remembering the boreal Grey Jays (also called Canada Jay) from my last trip, I inquired if they were breeding here as well. Indeed! In fact, at the moment they were busy building nests for their offspring. They depend on the black spruce in the bog to act as mini-refrigerators to keep the food cold, Julie explained. In the summer, they’re busy storing food in the crevices of many of these black spruce trees. Their palate is wide and varied, yet meat is the preference, so the coolness of the bog is important to prevent their stock from spoiling. When you’re building a new home in the winter, who has time to hunt for a whole new cache of food from venison roadkill or other hunted mammals?

Their sharp memories aid in tracking back to each of the cached stock locations, explains Julie. How will this bird fare as the temperatures rise? It is a fair question. ”If things warm up too quickly, the survival of their offspring is reduced,” said Julie. Currently, the Grey Jay is not listed as a species of concern, yet, the southern edge of the boreal forest in Canada and northern Minnesota may see this change in the future. Long-term 40-year studies in Algonquin Provincial Park of Ontario, Canada currently point to a decrease in nesting Grey Jays.

While slowly driving down the road, scanning the tree tops and branches, windows cracked, Julie received a text from a fellow birder. “Looks like we’re not the only ones birding here today. A flock of Bohemian Waxwings are visiting a nearby farm, would you like to see them?” I was delighted. This bird has been rare this season, and the tree of Crabapple berries where they were feasting was just behind us a half mile. Three or five-point turns are critical on this road, as a very wet and swampy ditch or waterway below the snowy surface awaits any significant weight on either side. My friend had us there in no time.

There, at the base of the driveway, stood a Winterberry tree, loaded to the gills with bright red berries, shiny, waxy and ripe. For a Bohemian Waxwing, this must be like walking past the fresh baked goods section at the farmer’s market. How do you resist? I eagerly walked closer to the tree, scanning, scanning. Nothing. No movement. Retreating back to the car, we sat and waited. Moments later, the entire flock descended from the pine tree down onto this fruit tree. Gorging and jumping from branch to branch, it was a true berry festival in full display. This grey bird is strikingly beautiful, commanding reverence with its pronounced crown, and pirate stripe across the eyes, slicing between intonations of red and orange on its face. Its bright yellow band on the tip of the tail and a stripe on the wings, as if an artist just applied its final touches and set it free. Fruiting trees near open bogs are favorite locations, and this one seemed to fit the bill.

As we moved away from the farm to return to the bog, a stand of Aspen trees stood up on the edge of the field. These are the Aspen Uplands, advised Julie, where more hardwood trees can survive on a sandier soil. The smattering of farms, in general, were also located in the more elevated parts of this mosaic of habitats.

Some of these higher grounds with deciduous trees stood on sand deposits from ancient beach ridges of glacial lakes. This area specifically was located on Glacial Lake Upham.

A dominating presence of tamarack trees took over as we explored lower areas of the bog. Despite the spindliness of these grey trees with what looks like peeling bark, they are a deciduous conifer that provides life for lowland conifer-dependent species. Two of these boreal specialists, the Black-backed Woodpecker and the American Three-Toed Woodpecker, had drilled cavities into the trunks. In addition, they had stripped off all of the bark of several dying tamaracks in order to eat the insects underneath, exposing the bare red wood underneath.

As we listened to a Black-backed Woodpecker tapping at a tree, we were assured it’s not the birds that are killing these trees. The insects underneath have been too much of a good thing for conifer-dependent birds. Specifically, the native pest known as the Eastern Larch Beetle. This beetle infests and kills tamarack trees. I wanted to learn more, so later asked a researcher who studies the ecology of this habitat, Dr. Alexis Grinde. “Since it’s warm enough now, the larch beetle is having two breeding cycles instead of one each year. As a result, vast amounts of tamaracks in northern Minnesota forests have been killed. We’ve seen spikes of increase in the Black-backed Woodpecker where known increases of larch beetle infestations have been documented,” she reported. Grinde is the Wildlife Ecologist and Research Program Manager at the Avian Ecology Lab of the University of Minnesota, Duluth, Natural Resources Research Institute (NRRI). She studies lowland conifer-dependent birds in these forested peatlands and conducts research to inform land management practices to preserve the species diversity in Minnesota’s birds.

I asked her why these birds generally come to the bog and breed here. “They have evolved to be a part of this lowland-conifer system,” she explained. “Because it’s so unique, they are habitat specialists to breed in this type of forest; the uniqueness of the mosses, plus the older trees, and the cavities, plus the water, and a lot of bugs available.”

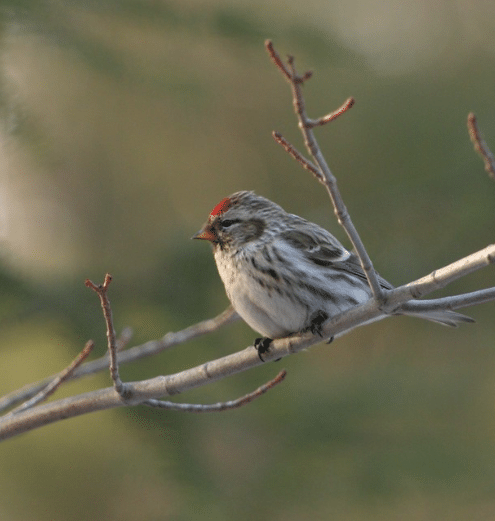

Speaking of evolving, as my toes thawed in the car that day, Julie Grahn pointed out boreal birds who have developed unique body parts and methods to survive in these frigid conditions. Both the roughed grouse and the common redpoll regularly roost in the snow. They go under the snow to escape the harsh elements, like the wind. “It’s warmer down there, perhaps 30 degrees compared to -30 degrees above the snow. They’ll survive a couple of days down there.” In addition, the Redpolls have special pouches in their throat for food storage and can keep their body temperature up at night by regurgitating and swallowing that food. “It’s kind of like having snacks all night long to keep their body temps up.” Whereas the black-capped and boreal chickadees, who can quickly put on fat, roost in the tree cavities and lower their body temperatures at night. At dawn, they start shivering and using their brown fat to warm themselves up so they are ready to look for food in the morning.

Less commonly seen in recent years, Spruce Grouse are also well designed for winter survival in these coniferous forests. They grow extensions in their intestines where substances are produced to help them digest their primary menu items in the winter, jack pine and spruce needles. “They also grow pectinations alongside their toes to help them grip better on icy branches and to give them more surface area, like a snowshoe would for your foot,” explains Julie, “to stay on top of the snow when they’re walking around.” These fringe-like growths are shed in the spring when they’re no longer needed.

Our time in the forested peatlands of Cook, Minnesota was packed with colorful insights into the lives of these boreal birds. The tour of birds was capped off just as we headed into town for a delicious veggie bean wrap and pasty with sweet potato fries. Poised on the distant top of an aspen tree sat one of the visiting jewels of the bog, the Northern Hawk Owl, surveying the scene. He sat just far enough, calmly returning my stare, towering over the bog. It was as if he knew I truly needed a better set of binoculars and longer lens to see and capture him in all of his glory. Maybe he would be here when I return in the spring to hopefully find a Connecticut warbler. We headed back with full hearts and plenty of reasons to keep learning and experiencing this joy of birding in northern Minnesota on a winter’s day.