By Laura Puckett, Wilderness News Contributor

As iconic as the tall pines or the swaths of exposed granite in Quetico-Superior is the image of a canoe cutting a delicate wake across smooth water. The canoe fits in the landscape, an organic product of the Native American’s efforts to take advantage of the area’s unique aquatic ecosystem. Today, the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness and Quetico Provincial Park exist in large part because of this vessel. Canoeists campaigned loudly to create the parks, and the fleets that flock to them each summer demonstrate that they are important pieces of natural, and national, heritage.

Part of this heritage is the wood-canvas canoe which replaced the Voyageur birch-bark style canoe around 1875, and became the workhorse for modern explorers until the advent of aluminum, Kevlar and plastic after World War II. Today, those that seek out wood-canvas canoes are not looking for what is lightest or most rock-resistant. They are looking for a vessel that is functional, but also beautiful, and the purveyor of tradition.

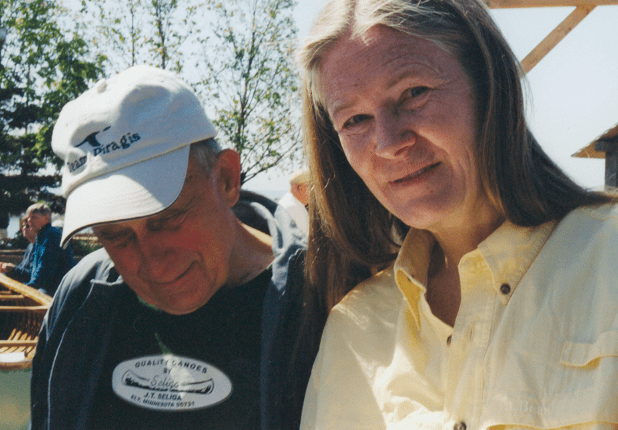

These canoes are hand-made by individuals scattered across the country. Joe Seliga was such a builder for over 60 years in Ely, Minnesota. He produced 621 canoes, many of which were used by YMCA Camps Widjiwagan and Menogyn, and were thus paddled each summer by hundreds of youths, instead of single owners. With this exposure, Joe gained a reputation unknown by any other individual builder. Thankfully, though, Joe was not the only builder out there, for he passed away last December, leaving behind him a long waiting list.

In his stead remain three established, if not necessarily famous, wood-canvas canoe builders in the Quetico-Superior region. Jeanne Bourquin is another resident of Ely, working just down the road from Camp Widjiwagan. On Lake Superior, Alex Comb is building canoes in the town of Knife River. Fletcher Canoes are built by Thelma Cameron in Atikokan, north of the Quetico. These builders each have their own techniques and their own style, producing canoes that are all a bit different. What binds them is their commitment to the process: the meticulous attention to details, the ability to work on their own terms, and the alchemy of using their hands and simple

materials to craft a beautiful product.

Jeanne Bourquin

Originally a Widjiwagan camper, Jeanne Bourquin paddled aluminum canoes while working for Outward Bound, but “got tired of that black stuff” on her hands, so she started learning to repair and build wood-canvas boats at Widji in between Outward Bound courses. She worked with Jerry Stelmock, a renowned Maine canoe builder, who helped her make her first form (the model on which new canoes are built), but she credits a lot of what she knows now to trial and error.

Eventually she designed her own model, the Otter, a tandem canoe for smaller people, inspired by the Widji trips that take 12-year-old campers into the BWCAW. She also produces the Lutre (a wider Otter), the classic Atkinson Traveler, as well as many other models with the high, upswept bow and deck profiles of the Chestnut Indian Maiden. She does a lot of repairs and sells yoke pads; she teaches classes at the North House Folk School; for new canoes, she averages about three a year, and is happy with that. Seliga’s legacy is admirable, she says, “he is an inspiration for how to be dedicated to something,” and how when you are, “it can give you lots of life,” but for her, building canoes is equally about constructing a way of life as it is about canoes.

Bourquin’s craft has enabled her to live in Ely, to be accessible to her family, and to work on her own terms—with people and by herself, for however much time she desires. Jeanne acknowledges that she doesn’t “have a wide-range, with other kinds of boats or wood-working skills,” but she is good at building canoes and explaining the process to others. She is grateful that with her husband’s income she doesn’t have to depend solely on her work to sustain her family, so she is able to enjoy building canoes, but also pursue other activities and go on paddling trips of her own.

Alex Comb

In contrast, Alex is proud that he is able to provide for his wife, older son, and new baby with his work. Like Bourquin, he does not just build new boats. He does some repairs, he works as a building inspector for a non-profit in Duluth, and he does a lot of private teaching. He would build more if he could, but hiring help hasn’t worked, and he does all he can now, popping into the shop connected to his house at odd hours to make a little progress. In the end, he doesn’t keep track of how many canoes he builds, “the number kind of weighs me down,” he says, “all those boats, it makes me tired.”

Comb is as much a boat designer as a builder—as evidenced by his 8 original models. He had a helpful background as a professional carpenter, though when he first started, all he had to go on was an Old Town displayed in a store and what advice he could wrestle from Joe Seliga, who was reluctant to share the techniques he had spent so many years acquiring. Today Comb has responded to the continuing demand for Seliga-style tripping canoes with his own model, the Stillwater, based on a canoe built by Geo. Muller Boatworks, in Stillwater, Minnesota, around 1935. Canoe design is not radical, Comb says. He stresses that “the true success is not the extreme, the something that’s way out there;” rather, it is “the something that is right in the middle, but everyone missed it.” For him, this creative process is the most fulfilling aspect of his work, when he is able to see things he’s been mulling over become realities.

Thelma Cameron – Fletcher Canoes, Atikokan Ontario.

Thelma Cameron

On the other side of the Quetico, Thelma Cameron is building the canoes her uncle, Paul Fletcher, designed: the Bill Mason Heavy Duty, a large tripping canoe, and the Fletcher Fancy, a smaller boat with high, upswept ends. Paul Fletcher started to build canoes in 1985, but wanted to retire about the same time Thelma and her husband visited him to pick up a canoe for themselves. In 1993 the Camerons bought the business and moved the canoe form and tools to Atikokan, where Randy and their son built the canoes for 4 years. When their son decided to move away in 1997, Thelma didn’t want to see the business end, so she learned all she could before he left, and today continues the Fletcher tradition.

Although she never could have predicted she would be doing this work, Fletcher feels like she has fallen into the perfect job. She has no prior wood-working experience and has never been much of a paddler, but building the canoes is an extension of the rest of her life. “My most important feature is my hands,” she says, “I build the canoes, I’m an artist—I quilt and sew—everything I do, I do with my hands.” She speaks in glowing tones about how “every single canoe is different” because the wood has a mind of its own, and it is up to her to work with it, to select the most compatible pieces and to marry them for their beauty. She doesn’t teach, so she can keep her own hours and be there for her grandchildren, and she doesn’t design canoes, because she doesn’t feel she has the mechanical expertise for it. Cameron is just abundantly happy to be building, producing up to 12 new boats a year, and she is proud her work is good enough to please her uncle and her clients.

Each of these builders acknowledged that theirs is a labor of love. If they were in it for the money, they would have abandoned it years ago. They persist because of the way the work enables them to live and because of the reward in producing a thing of beauty with their own two hands. Comb always knew he would be a craftsman, Cameron never could have guessed it. Bourquin and Comb grew up paddling in the Northwoods and sought out wood-canvas canoes, while Cameron inherited the family business. However they came by their craft, whether they produce 2 boats a year or 12, they build canoes because it fits with something inside of them.

This “fitting” is at the core of the wood-canvas canoe. From the pieces of wood that are carefully selected to create a hull, to the way a loaded canoe moves easily across the Quetico-Superior waterways, the wood-canvas canoe is about finely fitting components together.

E. B. White once described how the beauty of a boat is in how well-suited it is to its function: “I do not recall ever seeing a properly designed boat that was not also a beautiful boat. Purity of line, loveliness, symmetry—these arrive mysteriously whenever someone who knows and cares creates something that is perfectly fitted to do its work.”

The wood-canvas canoe is such a carefully designed vessel, but White only alludes to what is essential for Jeanne Bourquin, Alex Comb, and Thelma Cameron—the way the builder contributes to this beauty. As much as the wood fits the canoe, the canoe fits the

landscape, and the form fits its function, so does the craft fit the craftsperson—every piece coming together perfectly.

This article appeared in Wilderness News Fall 2006