Fire brings life in many ways to the boreal forest, and shapes the ecosystem as much as climate, the water, and bedrock. From helping sow jackpine seeds to providing the young aspen that grouse and moose like, fires create as much as they destroy.

The black-backed woodpecker (Picoides arcticus) is a prime example. This is a bird of the burned boreal forest, and rarely breeds outside areas recently subjected to fires. Primarily eating the beetles that thrive on dead trees, one study showed that, in a burned jack pine and black spruce forest in the Great Lakes region, black-backed woodpeckers “foraged almost exclusively on severely burned, mostly dead, jack pines that contained an abundance of wood-boring insects.”

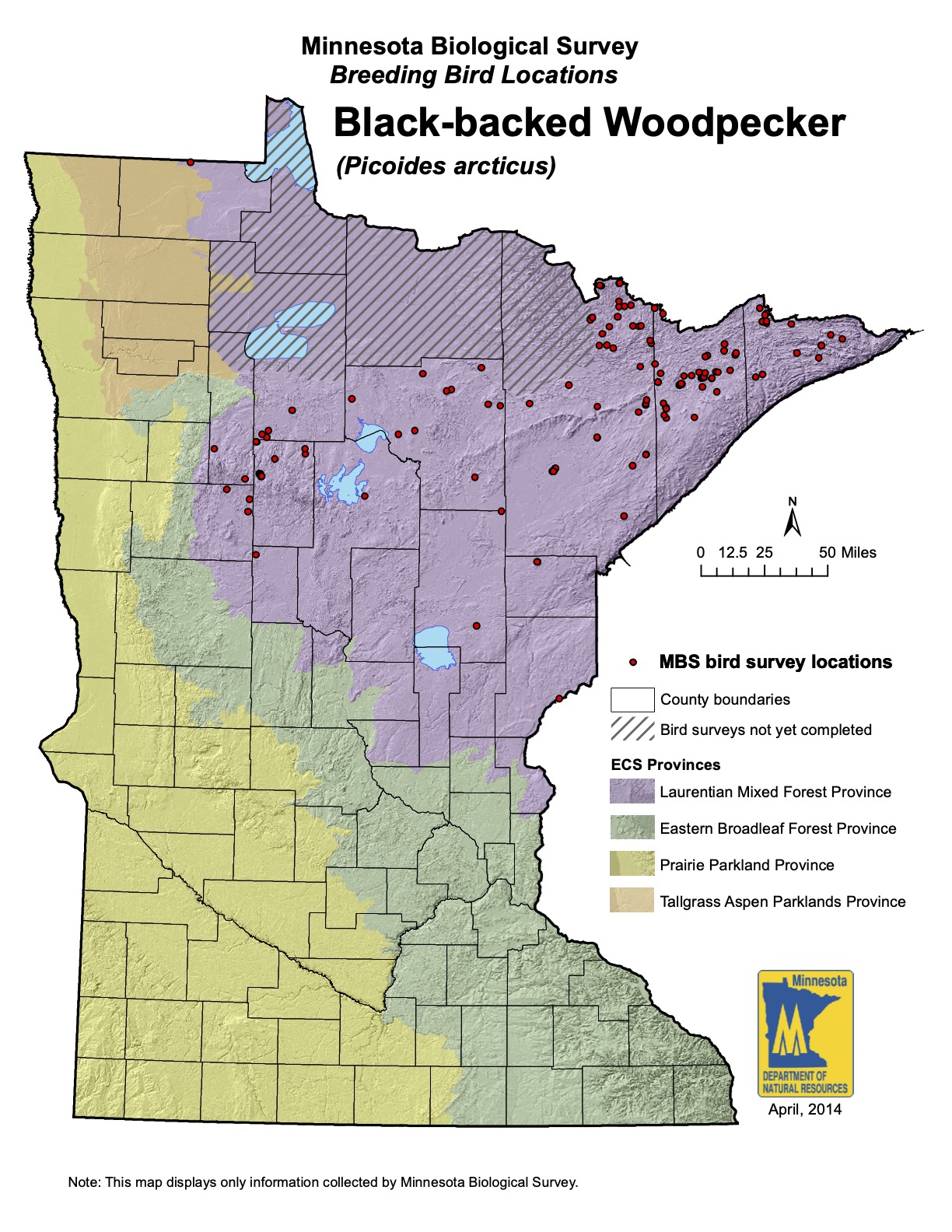

But, while its range spans much of Canada and northern Minnesota, its population is low and spread sparsely across the vast landscape. That’s because of its dependence on post-fire forest habitat, which is usually widely scattered.

The study in the post-fire Great Lakes jack pine and black spruce forest found that black-backed woodpecker, which were not present at the site before the wildfire, established territories within the first year after a fire. It then became one of the three most influential bird species in the area.

But, then, within a few years, the habitat is no longer suitable, and the birds disappear. It’s a testament to the species’ sensitive needs. A study in Quebec showed that, for three years after a severe wildfire, nest density was among the highest recorded for the species. Scientists also observed nest density decrease rapidly; by the second year post-fire, nest density was around half what it was the first year after fire.

Because of its small population, disjunct locations, and tendency to move great distances, the black-backed woodpecker is not frequently seen by people. This also means many questions remain about the bird’s life cycle, breeding, habitat, and more.

What is known is that the species is a medium-sized woodpecker nine inches long, weighing two to three ounces, with a wingspan of about 10 inches. Adults have solid black upperparts, while their underparts are white and heavily barred with black on the sides and flanks. Males have a prominent yellow patch on the center of the crown.

It is unique among woodpeckers, except for its close relation, the even rarer three-toed woodpecker, in having three, not four toes. It has two toes pointing forward and one in the back.

And it is inextricably linked to forest fires. Not just any forest fires, either, but it clearly prefers recently burned mature forests over any other age. The study in Quebec found that nest density in burned mature forest was almost double that in burned young forest.

The black-backed woodpecker looks different than any other woodpecker in Minnesota, except for the related three-toed woodpecker. The black-backed can be distinguished by its entirely black back, a stripe behind the eye which does not extend down neck, and entirely white outer tail feathers.

The species nests in tree cavities it extracts, with both male and female working on the nest. They usually lay three to four eggs in June, only producing one brood per season. The adults feed the chicks for about 25 days before they fly the nest, and the parents continue providing food for several weeks after fledging. The young follow the adults around, learning from their techniques of finding larval and adult insects.

“Black-backed Woodpeckers are not known to migrate, but do, on occasion, irrupt from their resident range,” the U.S. Forest Service says. “This sometimes results in remarkable flights of abundant proportions over extended distances.”

In 1987, ornithologist Robert Janssen reported that black-backed woodpeckers were more abundant in northern Minnesota in winter rather than summer, likely because of a short fall migration and an “exodus” to breeding grounds in spring.

The Minnesota Biological Survey has recorded 139 breeding season locations of the Black-backed Woodpecker, distributed from northeastern Becker County, Clearwater County, and northwestern Todd County to Cook County. Most were in Cook County and northern Lake and St. Louis Counties. In 1932’s “Birds of Minnesota,” ornithologist Robert Thomas reported that the bird was common in Carlton County — perhaps the massive wildfires of 1918 around Cloquet, and many more in the intervening years, contributed to the birds finding suitable habitat.

Their diet is relatively restricted to a few family of beetles commonly found in burned forest and dead trees: mountain pine beetles, wood-boring beetles (Cerambycidae and Buprestidae), and engraver beetles (Scolytidae).

While the black-backed woodpecker’s population across the continent is believed to be stable, it is cause for some concern. One of the biggest threats to the bird is the suppression of fires. Long-standing policies of putting out wildfires has reduced its available habitat, while post-fire logging to remove burned trees can also remove valuable resources.

The black-backed woodpecker’s population along the Pacific Coast is under consideration for Endangered Species Act protection. In Minnesota, the Department of Natural Resources considers it a “species of greatest conservation need,” largely because of habitat loss due to wildfire suppression.

More information:

- Conservation Assessment for Black-backed Woodpecker (Picoides arcticus) – U.S. Forest Service (PDF)

- Picoides arcticus – Fire Effects Information System – U.S. Forest Service

- Black-backed Woodpecker (Picoides arcticus) – Minnesota Breeding Bird Atlas

- Black-backed Woodpecker – Audubon