Black ash trees, one of the most common deciduous trees in the Quetico-Superior region, are a key part of the region’s ecosystem. New research explains how the ripple effects of the invasive emerald ash borer, which kills ash trees, could change habitat for other wildlife.

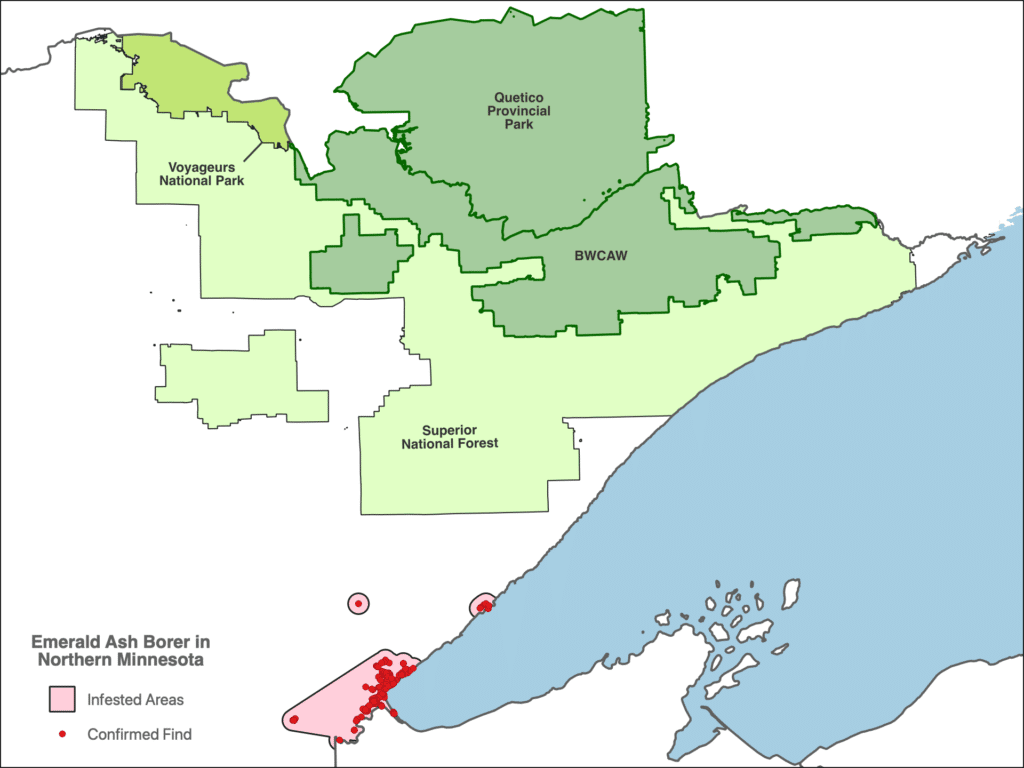

Emerald ash borer (EAB) was first found in Minnesota in 2009, and has slowly but steadily spread through the state. In 2015, it was first found in the Duluth area, on the edge of the Superior National Forest. Last April, the Minnesota Department of Agriculture reported the insect had been found along the Superior Hiking Trail in Two Harbors.

The invasive species only expands its range by people transporting wood.

In the latest study, scientists provide data showing how black ash wetlands are home to many unique species that are not found in the surrounding landscape. Loss of the trees could ultimately reduce the number of bird species in northern forests, while perhaps benefiting frogs. That’s because the amphibians like sunnier spots, while many bird species depend on complex forest structure for food, nesting, and other needs.

“If EAB invades these systems, expected increases in ponding and canopy openness may be beneficial for some anuran species during the breeding season, but loss of the forest canopy could result in significant changes in bird community composition,” the authors wrote.

The study was led by Dr. Alexis Grinde of the University of Minnesota’s Natural Resources Research Institute. Also involved were experts from the U.S. Forest Service, Chicago’s Shedd Aquarium, and the University of Vermont.

The researchers compared the species that are found in black ash wetlands to nearby uplands, which were primarily forested by aspen trees. They found that, as is often the case, the wetlands had more biodiversity than the uplands. One reason is more water means more insects and other invertebrates that birds particularly depend on during breeding and nesting seasons. But if the vegetation in those wetlands shifts away from black ash, there could be significant impacts throughout the food web.

Wetland wildlife

Winter wrens are often found in black ash swamps, and require dense undergrowth and down wood for nesting and foraging during the breeding season. Lake County, Minn.

If the ash trees disappear and boggy areas become more open, it could provide some advantages for frogs. The researchers found more specimens and more species in open wetlands than in black ash swamps. The open wetlands generally were wetter and stayed that way more of the year, while the black ash swamps tended to dry out more quickly. A species like the wood frog might breed and lay eggs in the open wetlands, but then spend much of their adults lives in the nearby forests.

Two years ago, a Forest Service study described the broad threats to the region’s black ash wetlands as a serious concern, because the trees dominate the swamps where they grow, and few other native trees can replace them. The wet, acidic soils of the wetlands are generally only habitable by black ash, tamarack, and white cedar. But tamarack are currently being decimated by infestations of the eastern larch beetle, probably helped by global warming, and white cedars are being suppressed by increased whitetail deer numbers.

While loss of ash may be impactful in mixed-species forests, these impacts may pale in comparison to the potential impacts when a single ash species makes up the majority of overstory trees, as in black ash (Fraxinus nigra

Marsh.) wetlands of the western Great Lakes region of North America,” the authors wrote.

Forests of the future

The 2021 study and the latest paper also touch on possible management activities that could mitigate the damage from EAB and the loss of black ash wetlands. The previous research indicated several potential species that could be planted, including swamp white oak (Quercus bicolor Willd.), hackberry (Celtis occidentalis L.) and a Dutch elm disease tolerant variety of American elm. Neither swamp white oak and hackberry are considered native to northern Minnesota, but are found farther south in the state. Elms are native to the entire state.

The most recent study suggested that species should also be chosen based on the type of forest structure they provide in wetlands.

“Management strategies that focus on emulating structural complexity of black ash wetlands while establishing non-host alternative native trees species that will maintain long-term forest cover are necessary to conserve critical habitat that supports wildlife diversity,” the paper says.

In 2007, the Superior National Forest introduced new rules for firewood in part to prevent Emerald Ash Borer from reaching the region. It is now illegal to transport firewood into the National Forest from outside Minnesota, or from any county under an emerald ash borer quarantine.

References

- Grinde, Alexis R.; Youngquist, Melissa B.; Slesak, Robert A.; Palik, Brian J.; D’Amato, Anthony W. 2022. Evaluating At-Risk Black Ash Wetlands as Biodiversity Hotspots in Northern Forests. Wetlands. 42(8): 122. 16 p. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-022-01632-9.

- Brian J Palik, Anthony W D’Amato, Robert A Slesak, Wide-spread vulnerability of black ash (Fraxinus nigra Marsh.) wetlands in Minnesota USA to loss of tree dominance from invasive emerald ash borer, Forestry: An International Journal of Forest Research, Volume 94, Issue 3, July 2021, Pages 455–463, https://doi.org/10.1093/forestry/cpaa047

- Youngquist, Melissa B.; Eggert, Sue L.; D’Amato, Anthony W.; Palik, Brian J.; Slesak, Robert A. 2017. Potential effects of foundation species loss on wetland communities: A case study of black ash wetlands threatened by emerald ash borer. Wetlands. 37(4): 787-799. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-017-0908-2.