By Alissa Johnson

“I have never had a car or driver but have lived on a big wide-open stage and seen a whole pioneer period pass—probably the last.”– Ober, 1957

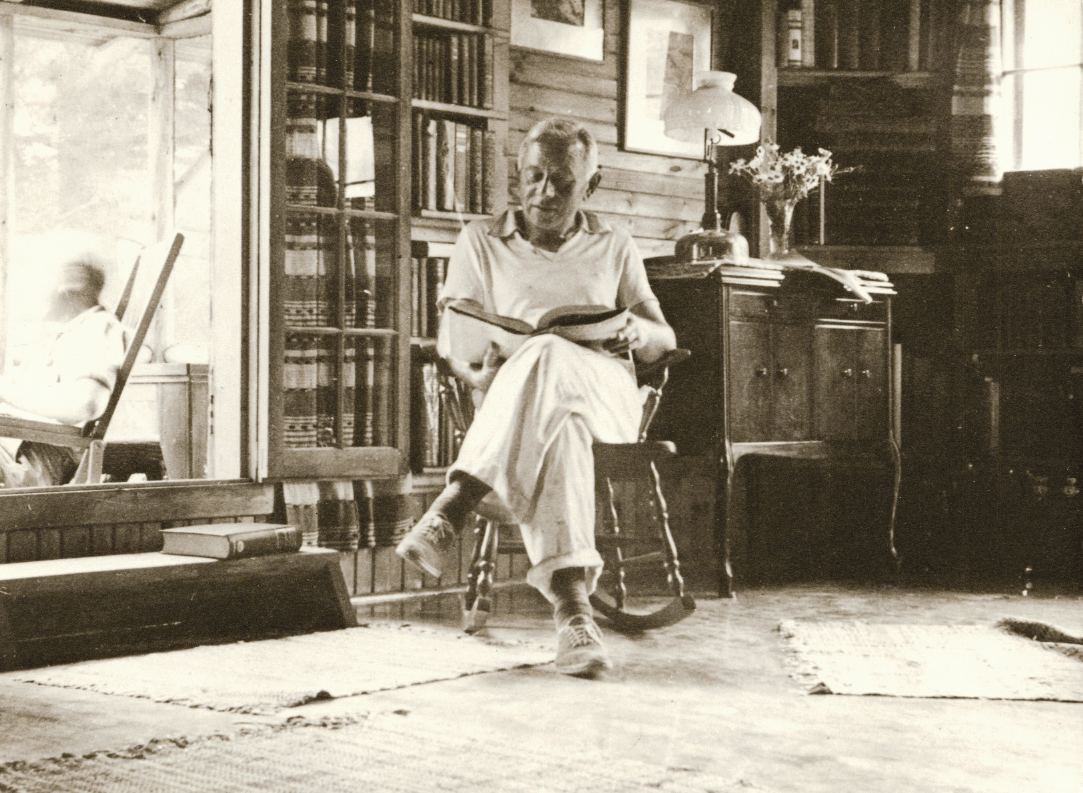

As a Harvard graduate, Ernest C. Oberholtzer wanted to write. At the age of 25, he paddled 3,000 miles in the Rainy Lake Watershed in one summer, selling his notes and photographs to the Canadian Northern Railroad. Three years later, in 1912, he paddled to Hudson Bay and back, thinking he would write about his trip and it would become his legacy.

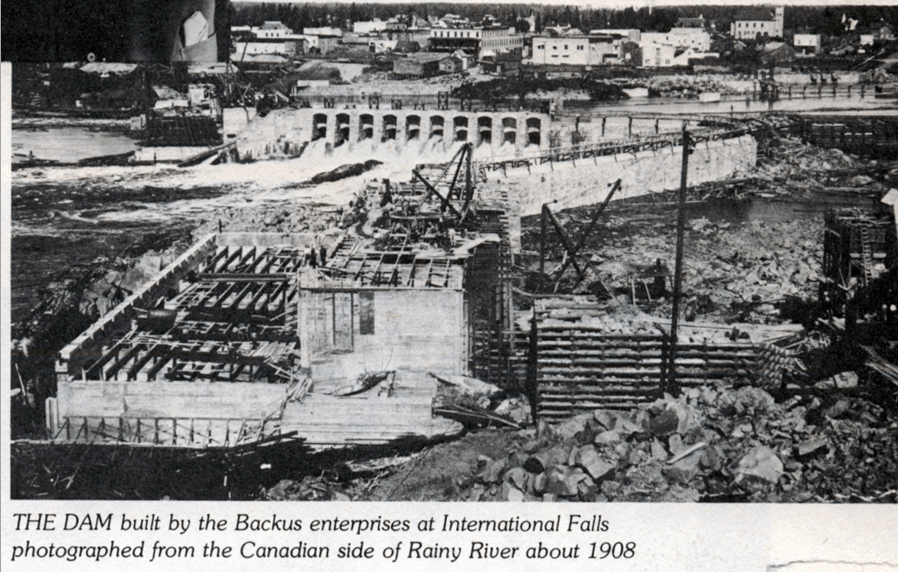

But in 1925, lumberman Edward Backus proposed building seven dams on the international border. The dams would have raised water levels 80 feet, submerging Lac la Croix’s islands. At Basswood Falls, the water would have been so high there would be no waterfall. The plan didn’t sit well with Ober (as Oberholtzer was called). He testified before the International Joint Commission, the Canadian and American review body considering Backus’ proposal. With his friend, attorney Sewell Tyng, Ober filed a brief arguing that power development was not the region’s only asset. The men had an alternate plan based on the belief that the public’s interest in the land lay in canoe trips and building summer homes.

“When you destroy the beauty of that region, you destroy its utility,” Ober said.

A New Voice

Ober’s vision came at a time when much of the public conscience was still rooted in development. President Theodore Roosevelt established the Superior National Forest in 1909, and in 1922, Forest Service ranger Arthur Carhart proposed the first management plan based on recreation. But the power of development and Backus’ influence were so widespread that a group of Minneapolis men met in secret to strategize opposition to Backus. A dozen strong, they convened in a basement until they learned of Ober’s idea—an international peace park. They saw in Ober the public face of a campaign to preserve the watershed. Three men in particular convinced Ober to lead an organization they would call the Quetico Superior Council: Charles S. Kelly, Frank B. Hubacheck and Frederick S. Winston. Ober was reluctant at best; he believed it would be a “thankless job with some danger of failure.”

But the Minneapolis men were persuasive, and in 1927, Ober began traveling to Washington D.C. and Canada to develop his plan and lobby for its creation. He divided the watershed into three zones: a primitive inner zone; a middle zone open to camps and trails; and a perimeter open to railways, highways, private homes, resorts and businesses compatible with wilderness. Ober believed recreation and modern forestry could work together, leaving shorelines intact and restricting logging to areas the public never saw.

“Destroy the beauty of the visible shores and islands of these lakes and rivers and you destroy the whole charm and pleasurable utility of the region for the public,” Ober wrote to President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

But Ober did more than meet with politicians and public officials; he reached out to citizen groups like the Izaak Walton League and even many women’s groups forming at the time. He persuaded the latter to write and call their representatives, and whenever possible, brought decision makers to Rainy Lake, hosting them at his Mallard Island home and taking them on canoe trips. With the backing of the Council, he brought a new voice to the debate over the north country.

Victories Versus a Vision

During the late 1920s and 1930s, Ober and the Council helped pass legislation key in ending Backus’ plan. In 1930, the Shipstead-Newton-Nolan Act prohibited homesteading, the alteration of water levels, and logging within 400 feet of shorelines. It was perhaps Ober’s greatest contribution to the cause. In 1933, Minnesota extended similar protections to state lands. In 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt established the President’s Quetico-Superior Committee—Ober was an original member. And in 1936, he helped found the Wilderness Society. His work unarguably laid the foundation for protecting the border lakes region. But for Ober, legislation was merely “a protective measure, primarily aimed at the Backus Project.” He still pursued his larger vision: a formal treaty creating an international peace park.

It was a political and often tiring fight. Time and again, Ober’s journal entries and letters to friends showed frustration and a desire to walk away. He wanted to return to Rainy Lake, paddling and spending time with the Ojibwe. He still wanted to write. But time and again, particularly through the support of long-time friend and financial supporter Frances Andrews, he reentered the debate. At one point, he is known to have said, “Common sense counsels me to drop the whole struggle… Common sense is a very small part of my make-up.”

During the late 1940s, however, Ober yielded the spotlight to Sigurd Olson. Public discourse had shifted from the broader vision of a peace park to details like fly-ins. Olsen and the Council helped pass legislation that prevented flights below 4,000 feet, but for Ober efforts that helped canoeists and recreationists often overlooked the needs of the native population. He returned to Mallard Island to preserve the Ojibwe culture, returning to the spotlight only on occasion. In 1955, he, Olsen, Kelly and Hubacheck (the Minneapolis men) hosted an international meeting to revive international treaty negotiations. In 1960, the United States and Canada exchanged letters declaring their intent to protect the region’s wilderness character and establishing an international advisory committee.

Ober’s vision of an international park never fully came to pass, and he died at 93, just one year short of the creation of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. But his vision fueled a century of public debate and wilderness protection, and it remains a vision from which we can draw inspiration. In the words of Mary Holmes, long-time board member of the Oberholtzer Foundation, “So often, as environmentalists or people trying to make change, we focus too small. We want to save that marsh, that 25 acres. Ober was trying to save a whole watershed. He had an enormous guiding vision.”

![The Shipstead-Nolan Act was a measure of national significance. It was the first statute in which Congress explicitly ordered federal land to be retained in its wilderness state, a precedent “giving legislative sanction to a new conception of land service, for the purpose of preserving the inspirational, spiritual, and recreational potentialities of [national forest] lands.”](https://queticosuperior.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Map-Shipstead-Nolan-Act-1024x647.jpg)

Sources: In addition to research in Saving Quetico Superior: A Land Set Apart by Newell Searle, the following long-time Oberholtzer Foundation board members shared freely of their knowledge to inform this article: Mary Holmes, Jean Replinger and Beth Waterhouse.

This article first appeared in Wilderness News Spring 2012