By Charlie Mahler, Wilderness News Contributor

In the Gunflint Trail region, which has seen its share of calamity in recent years in the form of blow-downs and forest fires, geologist Mark Jirsa thinks he has found evidence of a catastrophe so massive that the natural disasters we know today appear miniscule in comparison.

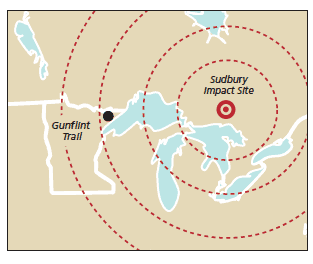

Off the north shore of Gunflint Lake, Jirsa, a geologist for the Minnesota Geological Survey, has found evidence of a massive meteorite impact that devastated a vast area of what is now North America and which may have radically changed the course of the planet 1.8 billion years ago. Although the mountain-sized meteorite slammed into the earth 480 miles away from the Gunflint, near what is now Sudbury, Ontario, Jirsa and others are finding evidence of the event in the rock of northern Minnesota, as well as near Thunder Bay, Ontario and in Upper Michigan.

What Jirsa and others believe happened millions of years ago is mind-boggling. Huge, hurtling meteorites seem more the stuff of science fiction and Hollywood than the usually placid Quetico Superior. But evidence shows that, like the Chicxulub Impact that caused the extinction of the dinosaurs, the Sudbury Impact likely changed the course of life on earth.

The Collision:

At ground zero, the collision of the meteorite and the earth’s surface caused an explosion so immense that the meteorite itself is thought to have vaporized on impact, leaving a crater more than 150 miles in diameter. Still

discernable today, it is the second largest crater known on earth. The seismic shock at the point of impact would have created a 10.6 magnitude earthquake, something unprecedented in

modern times.

Jirsa and other scientists believe that the impact felt along what is now the Gunflint – a shallow ocean at the time – shook the earth’s surface fiercely enough to break rock into a chaotic jumble. The area weathered a fireball and a blast of air that gusted to over 1,400 miles per hour, suffered a rain of semi-solid mineral hail falling from the sky, and endured tsunamis rolling across the land.

Across the whole planet, the meteorite’s collision with the earth is thought to have had life-altering consequences. Debris thrown into the atmosphere is thought to have obscured the sunlight across the entire planet, choking the fledgling life evolving at the time of its photosynthetic energy. The blue-green algae, called cyanobacteria, that was creating the earth’s first oxygenated atmosphere and depositing iron on the sea floor through its metabolism, suffered an extinction, ending the formation of iron on the planet save for a single blip in the geologic record millions of years later.

Across the whole planet, the meteorite’s collision with the earth is thought to have had life-altering consequences. Debris thrown into the atmosphere is thought to have obscured the sunlight across the entire planet, choking the fledgling life evolving at the time of its photosynthetic energy. The blue-green algae, called cyanobacteria, that was creating the earth’s first oxygenated atmosphere and depositing iron on the sea floor through its metabolism, suffered an extinction, ending the formation of iron on the planet save for a single blip in the geologic record millions of years later.

The Discovery:

Jirsa found his rocky evidence of the calamity during the modest modern-day catastrophe know as last spring’s Ham Lake Fire. In search of field trip sites outside the burn zone for a geological conference taking place in Duluth, he stumbled upon a rock outcrop off Gunflint Lake that looked familiar.

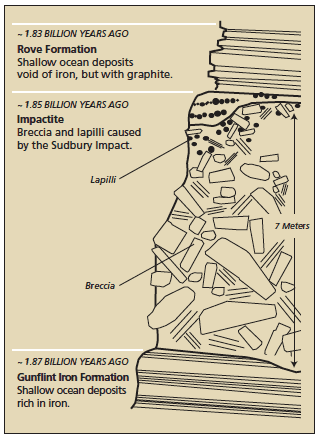

Jirsa noticed solid rock that appeared to be composed of small, pea-sized spheres and larger chunks of broken rock, called breccia, fused together in a single rock layer. Jirsa knew of similar rock, found by two high school teachers near Thunder Bay, which had been linked to the Sudbury Impact.

“I knew what this material might be,” Jirsa said. “It was at the right stratographic horizon and it had at least two of the attributes – it had the spheres and it had the broken rock fragments.” The spheres, called lapilli, are considered

evidence of the rocky hail that fell from the sky following the impact; the broken rock is thought to be the result of the seismic shock waves that rippled through the crust of the earth.

Further investigation of the rock showed diagnostic signs of deformation from a violent impact. Microscopic study showed quartz grains with fractures in a variety of orientations. “In order to cause this kind of deformation in a quartz gain,” Jirsa explained, “it takes pressures we can’t get on earth without invoking an extra-terrestrial impact.”

The Consequences:

The rock record shows that after the Sudbury Impact, the formation of iron on the planet soon ceased. The rock strata formed prior to the impact, the Gunflint Iron Formation, contains bands of iron formed in shallow ocean sediments. The layer of rock that Jirsa is continuing to discover on the Gunflint, which lies on top of the iron formation and is therefore younger, features the breccia, lapilli, and shocked quartz of the impact event. The rock layer above Jirsa’s “impactite,” which is even younger, shows sediments again accumulating in a shallow ocean, but without the iron bands.

The rock record shows that after the Sudbury Impact, the formation of iron on the planet soon ceased. The rock strata formed prior to the impact, the Gunflint Iron Formation, contains bands of iron formed in shallow ocean sediments. The layer of rock that Jirsa is continuing to discover on the Gunflint, which lies on top of the iron formation and is therefore younger, features the breccia, lapilli, and shocked quartz of the impact event. The rock layer above Jirsa’s “impactite,” which is even younger, shows sediments again accumulating in a shallow ocean, but without the iron bands.

“So, you had nice, quiet-water deposition of iron formation,” Jirsa describes, “and then, all hell breaks loose. Then it goes back to nice quiet-water deposition, but this time with no iron. There is a lot of graphite, though, graphitic mudstones. The graphite might be a product of an extinction event if those cyanobacteria that were forming the oxygen in the atmosphere that was causing the iron to precipitate out of sea-water, they probably were killed. They were carbon-bearing.”

As with most discoveries in science, the new answers discovered along the Gunflint Trail prompt additional questions about the nature of the earth before, during, and after the Sudbury event. Jirsa would like to know just how far the material ejected by the impact traveled and exactly what the meteorite hit when it cannonballed into the earth – did it impact hard rock or an ocean. It seems clear, however, that in the long geologic history of the Quetico Superior, a catastrophic event helped form the sometimes placid, sometimes chaotic, always wild region.

This article appeared in Wilderness News Summer 2008