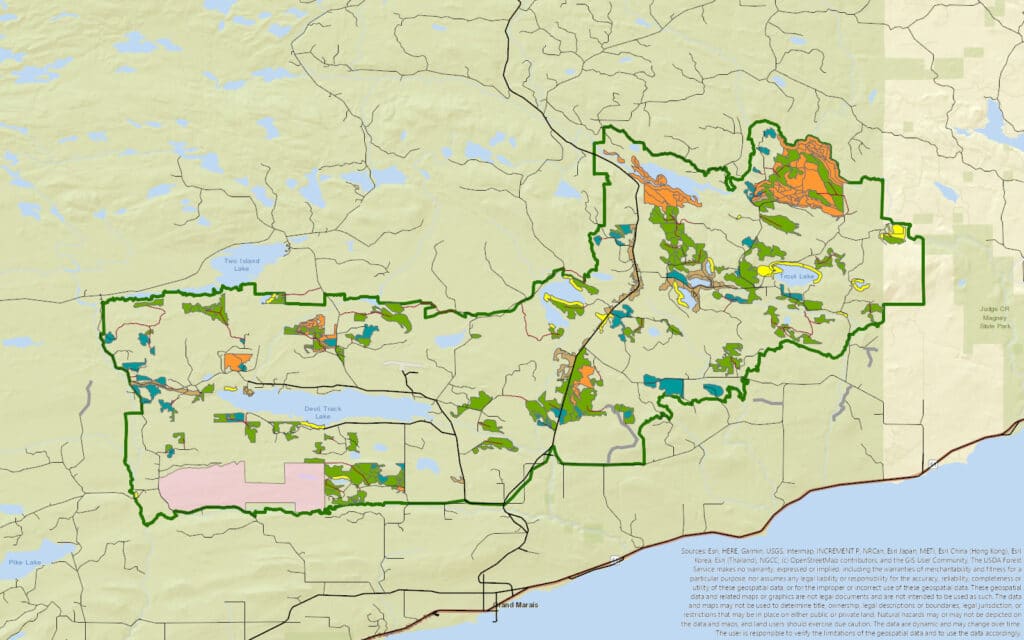

The Superior National Forest is proceeding with a management project on the southeast edge of the 3 million-acre Forest, including areas along the Gunflint Trail. The Kimball Project will include timber harvest, prescribed burning, tree planting, and other activities.

The project is intended to provide logging opportunities, reduce wildfire risks, increase wildlife habitat, improve forest health, and more. Management actions will be conducted on more than 45,000 acres of federal land. Implementation is scheduled to start already this year.

With significant logging, burning and other activities planned along the Gunflint Trail near Grand Marais, the Forest Service acknowledges the project “includes some of the highest use recreational areas in the Gunflint Ranger District.” In June, Gunflint District Ranger Michael Crotteau announced the agency had selected Alternative 2 from its Environmental Assessment.

“Alternative 2 will increase the long-term health and resiliency of the forest by moving toward landscape ecosystem objectives for age class, species, and diversity goals within the project area,” Crotteau wrote. “Wildfire risk will be reduced along the Gunflint Trail, improving both ingress and egress. Two prescribed fires near Northern Lights Lake and the Brule River will improve moose habitat and enhance mature upland patch dynamics. Harvest will provide a sustainable source of timber products, supporting local economies.”

A public comment period yielded several objections to cutting in some high-profile locations.

Plans to conduct logging along the Gunflint Trail and in the adjacent George Washington Pines Trail area, which is popular for skiing and snowshoeing, were a source of particular concern. While the project still includes clear cutting and thinning, the Forest Service says it took several steps to minimize the visual impact for visitors. But they say that some very visible stands will still have to be cut for the future health of the forest.

“Treatments along the Gunflint Trail are designed to meet long-term scenery objectives, realizing that scenic values may decrease in the short-term,” Crotteau wrote.

While the agency might normally include plans for visual buffers along the scenic byway, with strips of trees left between the road and logging areas, much of the forest along the Gunflint Trail in this area is not suitable because it is comprised of aspen, birch and balsam fir that would not survive long in that scenario.

The Gunflint Trail Scenic Byway Committee submitted extensive comments on the plan, asking to protect the historic route’s scenic qualities. They expressed concerns that the highway’s iconic stands of white pines will be reduced, while more stands of aspen will be present.

“All naturally occurring white pine should be retained for scenic, wildlife and local seed source purposes,” the committee wrote. “Activity in previously planted white pine stands should be aimed at correcting species imbalances so that they can retain the designation of white pine stands.”

Just six miles up the Gunflint Trail from Grand Marais, the popular George Washington Pines area includes a 3.3 kilometer cross-country ski and snowshoeing trail. The large red and white pines were planted by Boy Scouts in 1932 in what was then a recently-burned area.

Now, many of the pines are reaching the end of their lifespans, and the understory has become thick with balsam fir.

“It is important to me to ensure that healthy, regenerating forest following treatment will be visible from the ski trails,” Crotteau wrote in his decision letter.

Environmental advocates also said the plan for the George Washington Pines area was unacceptable, as it would maintain a planted and unnatural stand of pines, possibly for future timber harvest.

“Maintenance for continuation of pine plantations should not be part of vegetation management projects within the Superior National Forest,” wrote the Sierra Club. “The focus on prioritizing for current and future merchantability of forest stands needs to end. Rather, attention needs to be concentrated on restoring forest conditions that better represent the historical native vegetation communities.”

One common concern among commenters on the plan was the potential that more snow will drift across the ski tracks during the first few years after logging, as wind breaks are missing. In response, the Forest Service pledged to do extra grooming to compensate.

Across the Gunflint Trail, a large area of primarily quaking aspen will be clear cut, with six to 12 trees per acre left standing.

Other significant impacts include a small area of thinning that will take place along the Brule River, in an area deemed eligible for Wild, Scenic and Recreational River designation. There will also be some clear-cutting up to the edge of the Blueberry Lake Candidate Natural Research Area, another special site deemed worthy of protection, but no activity in the area itself.

The project will also include logging of aspen forests on two trails used primarily by ruffed grouse hunters. The logging is intended to provide the younger aspen forest that the birds prefer.

Approximately 32 miles of temporary roads will be constructed for project activities. Typically, the roads would be blocked off and decommissioned after work is done, but Native American officials with the 1854 Treaty Authority requested they be left open for 10 years to allow for increased hunting and gathering on lands they have legal rights to access.