Along the northern edge of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW) lies an invisible line. The international border stretches over 150 miles of water trail, following the shorelines of Quetico Provincial Park to the north and the BWCA to the south. Careful observers may notice the subtle demarcation of the international boundary as they paddle by. Short metal reference markers are punched firmly into hard granite rock. Flashes of metal gleam in the sunshine, indicating a clear line for visitors entering and exiting either country.

A shared passage

Under a mutual agreement between countries, people can share the portages and waterways directly along the border. Some visitors to the BWCA, a million-acre wilderness, paddle along the dividing line. If they hold a permit allowing it, they can venture further north. Quetico Provincial Park, also spanning over a million acres, is a coveted canoeing destination. It hardly appears any different from the BWCA, its wilderness neighbor to the south.

The Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842 defines the agreement for use. “It being understood that all the water communications, and all the usual portages along the line from Lake Superior to the Lake of the Woods; and also Grand Portage, from the shore of Lake Superior to the Pigeon River, as now actually used, shall be free and open to the use of the citizens and subjects of both countries,” the treaty declares.

History of the border

Starting in 1783 with the Treaty of Paris, both countries sought to define the border. By 1874, experts had surveyed most of the border as amended by later treaties. While some locations had markers like monuments, rock cairns, or mounds, there was a desire for more definitive methods.

In time, both countries established the International Boundary Commission (IBC) to complete a survey of the border, spanning from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean. In cooperation, each country appointed an expert geographer or surveyor as commissioner. As a result, they surveyed and established markers. According to Bryan Cloutier, IBC Engineering Technician, Central Regional Field Office in Minnesota, “Crews began installing metal markers starting in 1908.”

By 1925, the United States and Canada appointed the IBC as the permanent organization to maintain the boundary line. Therefore, the commission continues to be the managing agency responsible for documenting, maintaining and replacing the markers.

Boundary line and reference markers

The IBC oversees a swath of open land along the entire US border. The cut, extending ten feet on either side of the international boundary, is obvious from a bird’s eye view. Looking as though someone pushed a large lawnmower through, it’s intended to be visible. This passageway not only limits disputes but also defines a clear avenue for anyone who encounters it. The commission notes that “If you look along the international boundary between Canada and the United States in any forested area, it will appear simply as a 6 meter or 20 foot cleared swath stretching from horizon to horizon, dotted in a regular pattern with white markers. Over mountains, down cliffs, along waterways, and through prairie grasses, the line snakes 8,891 kilometers or 5,525 miles across North America.”

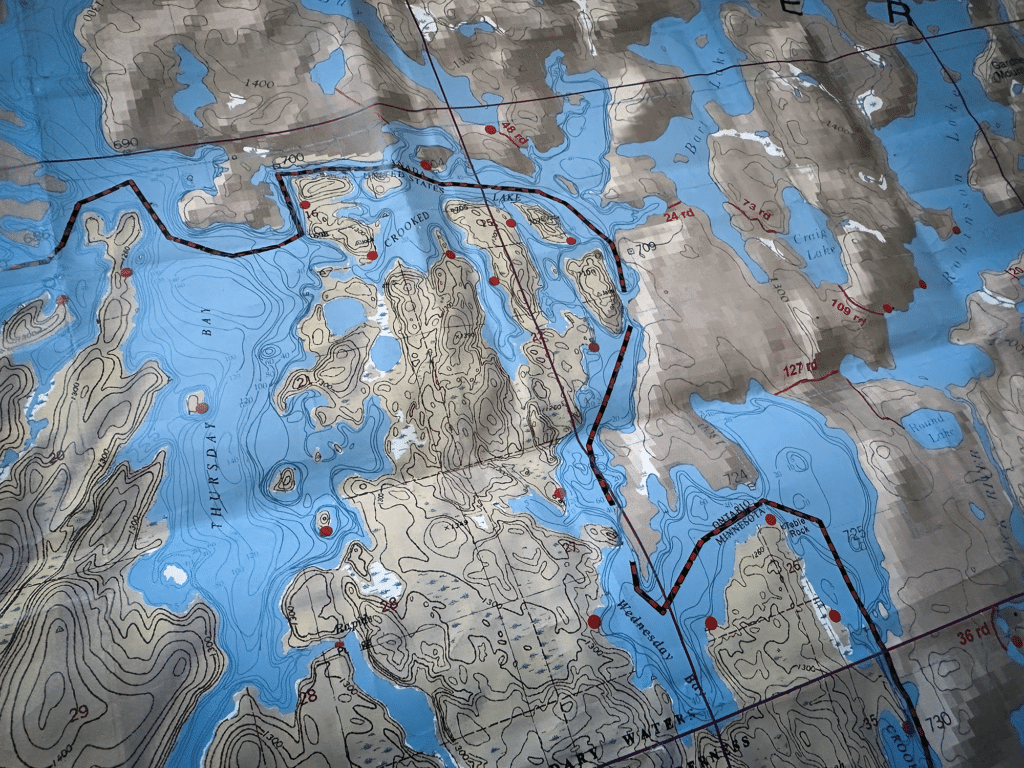

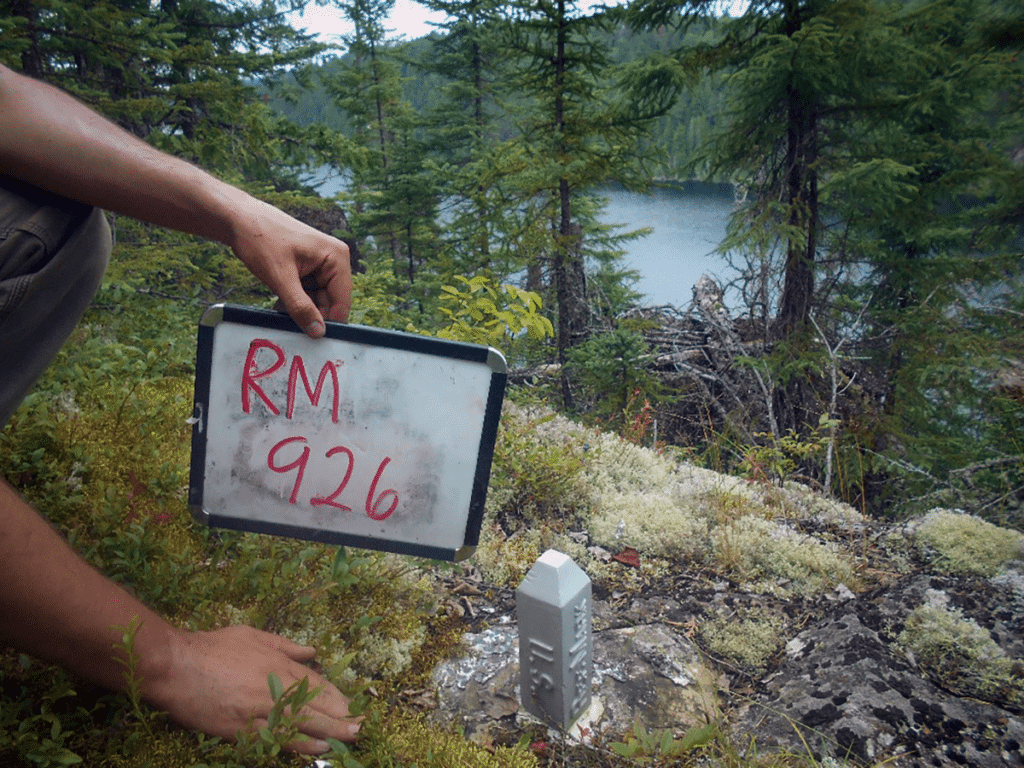

However, the boundary line along the northern edge of the BWCA is more subtle. A quick look at a map shows that the official border mostly bisects waterways. Along the imaginary line, eight-inch metal markers have been cemented into granite slabs near lakes. Where the reflecting landscapes come close together, similar markers may be seen on the Canadian side. “From Bottle Portage to South Fowl, there are about 700 reference monuments and 9 boundary monuments,” Coulter states. “Roughly half are on the Canadian side”. Some, he reports, are well hidden within the trees.

Looking closely one can see stamped letters on the facing sides of the marker. Identifying soil belonging to either the US or Canada, they often include the abbreviation “INT BDRY” for the international boundary. Additionally, most have reference marker numbers.

Separately, there are also small metal disks known as survey benchmarks containing data such as elevation. Those are in permanent locations throughout the region as well.

Monument markers

In a few key places, such as the Height of Land portage, the swath is wider. Along these portage trails are distinctive monument markers. Standing at shoulder height, they’re hard to miss. While some are conical in shape, others are obelisks. Built in segments, they are easily transported by canoe.

Furthermore, these markers are situated along historic portages that have been used for thousands of years. First by Indigenous people for canoe travel and later by European voyageurs who accessed them for the fur trade.

They not only delineate the international boundary but also highlight the Continental Divide. Waters here either flow north towards Hudson Bay or east towards Lake Superior.

Throughout the summer, IBC crews canoe into the wilderness with tools and materials needed to replace or repair the markers. The markers require ongoing care as falling debris, winter conditions, and storms can damage them.

Finally, with advancements in technology, surveys of markers and monuments within the BWCA are ongoing. Data is integrated into a Geographic Information System (GIS), enhancing the precision of the boundary line.

More info:

- International Boundary Commission

- Webster-Ashburton Treaty, 1842 – United States Department of State

- Links to additional treaties related to the establishment of the border

- Topographic maps of the BWCA and Quetico Provincial Park – McKenzie Maps

Wilderness guide and outdoorswoman Pam Wright has been exploring wild places since her youth. Remaining curious, she has navigated remote lakes in Canada by canoe, backpacked some of the highest mountains in the Sierra Nevada, and completed a thru-hike of the Superior Hiking Trail. Her professional roles include working as a wilderness guide in northern Minnesota and providing online education for outdoor enthusiasts.