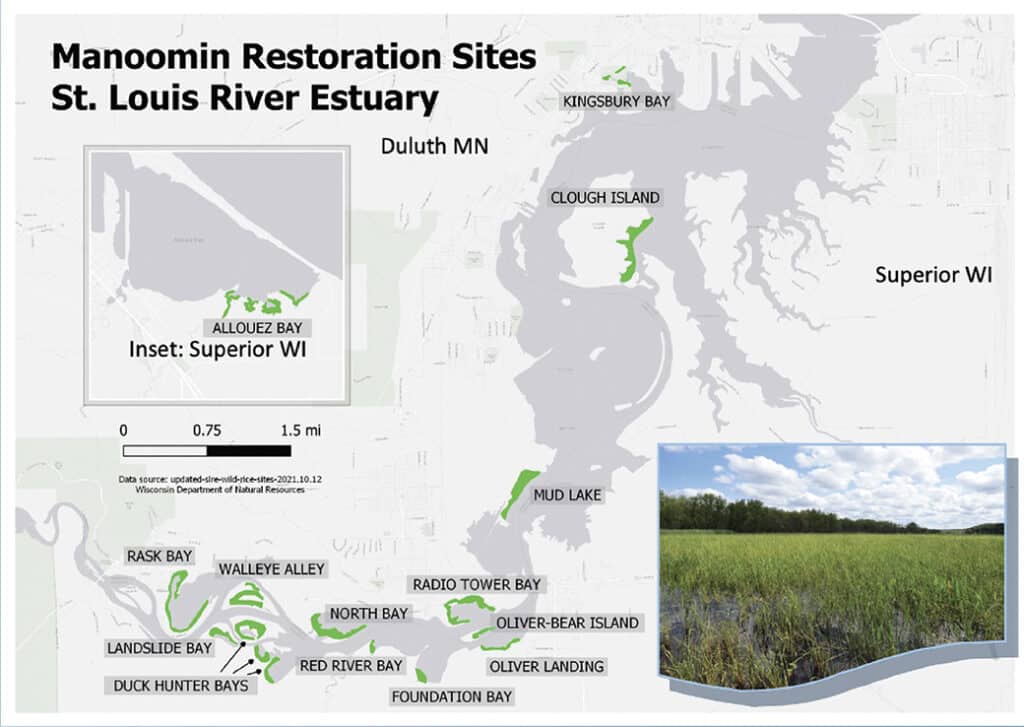

Canoes recently launched into calm waters along the St. Louis River Estuary, just south of Duluth, Minnesota. Their hulls carried 4,200 pounds of wild rice seeds. Between Allouez Bay and Kingsbury Bay, volunteers cast the seeds into the air. The seeds will settle into the soft, muddy bottom of the watershed and germinate in the spring. This work marks part of a long-term, multi-partner effort to bring back this once-thriving plant.

Restoring native wild rice

Last week, on a cool September day, groups of volunteers from the St. Louis River Alliance, along with partnering agencies, Tribal nations, and organizations, paddled into multiple areas near the port of Duluth, Minnesota. Their goal: to distribute 4,200 pounds of wild rice seeds across 275 acres of the St. Louis River Estuary. Before they began, Miranda Pacheco, a member of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe, gave a blessing over the rice and shared a story of resilience.

Over an area of twelve miles, they paddled, casting handfuls of seed in quiet bays and shallow waters along the way. Come spring, many of the seeds will sprout, starting another lifecycle.

Estuary held highest concentrations of rice

The estuary once offered an abundant supply of wild rice, known as manoomin, or “the good berry,” in Ojibwe. The Alliance reports that the watershed once supported up to 3,000 acres of wild rice, one of the highest concentrations in the region. Since then, industrial development, logging, and pollution have drastically reduced that footprint. Additionally, environmental groups and local Tribes have also argued that mining releases sulfates, which pollute the water and, in turn, impact wild rice reproduction and harvest.

The Anishinaabe people, also known as the Chippewa, rely on annual wild rice harvests. Wild rice, which is native to the Great Lakes, serves as both a vital food source and a sacred plant for them. In the Anishinaabe worldview, the health of the people is inextricably connected to the health of manoomin.

In his writings, Ojibwe elder Edward Benton-Banai (1985) explains that manoomin plays a central role in the Ojibwe migration story, noting that the historic manoomin beds in the estuary are especially significant as part of “the land where food grows on water.”

Still, according to the Minnesota DNR, Minnesota holds more acres of wild rice than any other state in the country.

Harvest done by canoe

Wild rice thrives in shallow water and slow-moving streams. The grains ripen late in the summer and are traditionally harvested by canoe. As the canoe weaves through the plants, harvesters bend the stalks using poles or sticks called “knockers.” One person brushes the seeds into the canoe while the other paddles slowly forward.

This annual grass reproduces each year from seed it drops in the fall. It grows between three and ten feet tall and produces clusters of ribbon-like leaves. By late August, yellow and reddish grains emerge at the tips of its stalks. In Minnesota, harvesters collect the rice from mid-August through the end of September. Rice beds also support a variety of wildlife and attract migrating waterfowl.

Fluctuations in precipitation and water levels make it necessary to seed wild rice for at least 3–5 years to establish it successfully. As a result, the Alliance has treated this as a long-term project. For the past ten years, they have led annual plantings to support the effort, and they plan to continue reseeding about 200 acres each year. In 2024, they updated their plan to identify areas in the estuary with the greatest potential for positive outcomes.

Partners in preservation

The Great Lakes Restoration Initiative has funded this project. Partners include the 1854 Treaty Authority, Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission, St. Croix Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, St. Louis River Alliance, Douglas County, Ducks Unlimited, Lake Superior Research Institute, Minnesota Land Trust, Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, and Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Further information can be found at the Alliance’s website.

More info:

- 4,200 pounds of manoomin planted – St. Louis River Alliance

- Manoomin Restoration Partnership – St. Louis River Alliance

- Wild rice management – Minnesota Department of Natural Resources