By Alissa Johnson

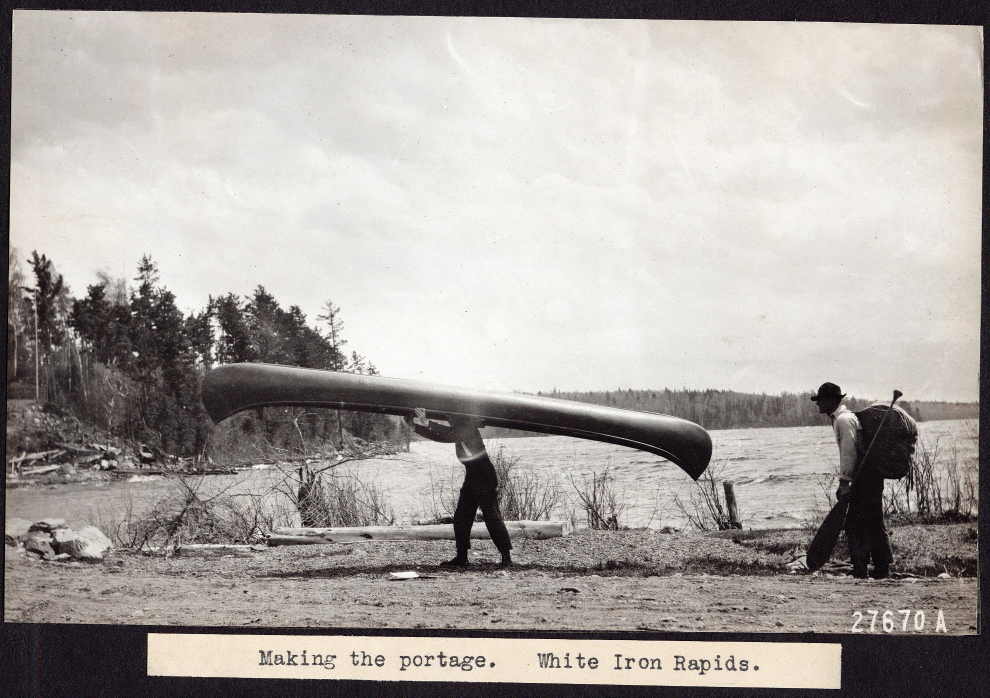

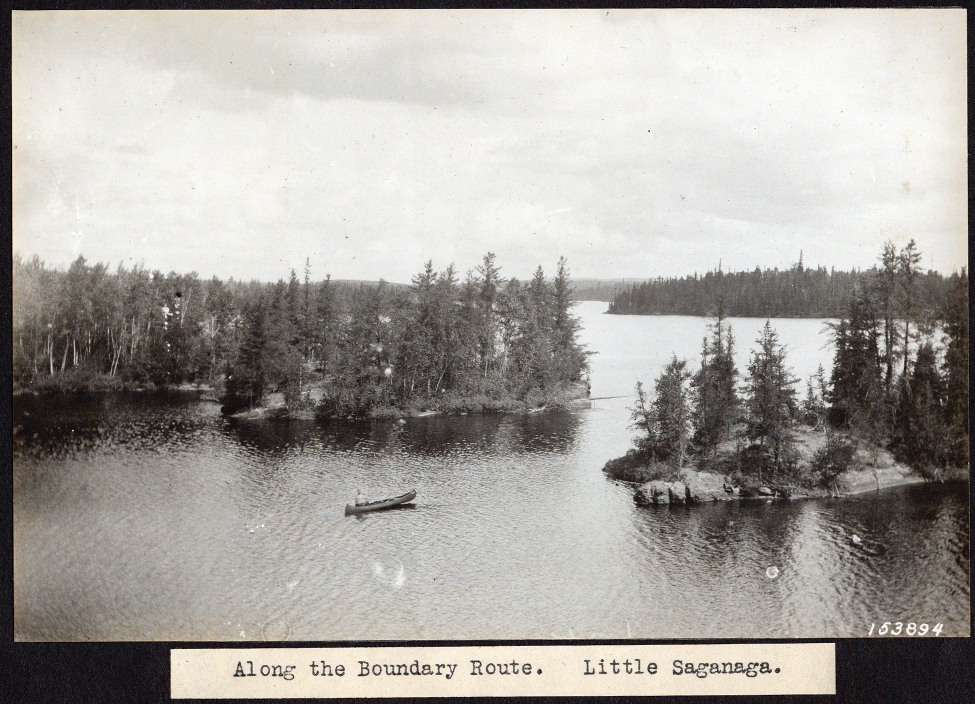

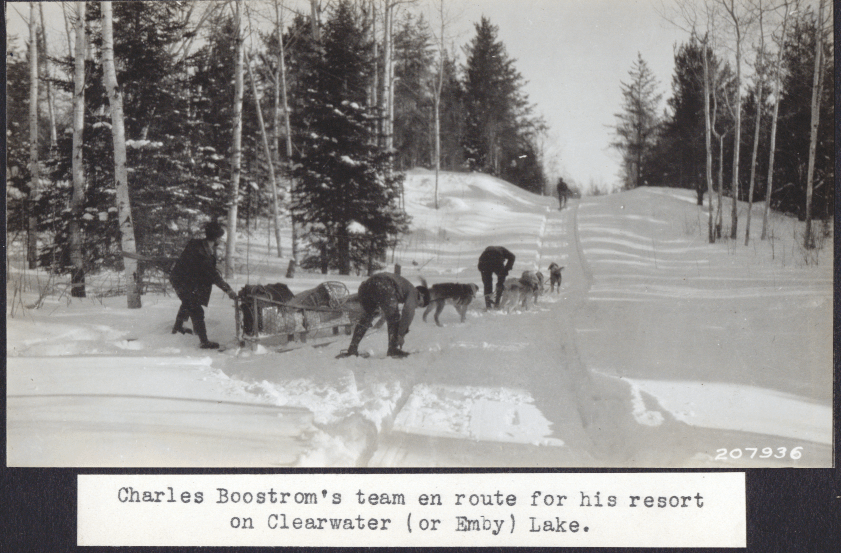

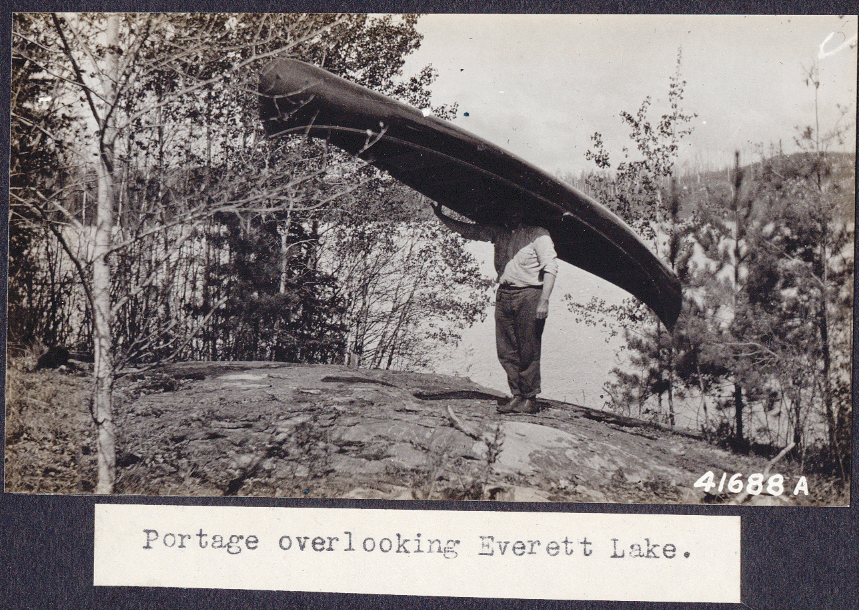

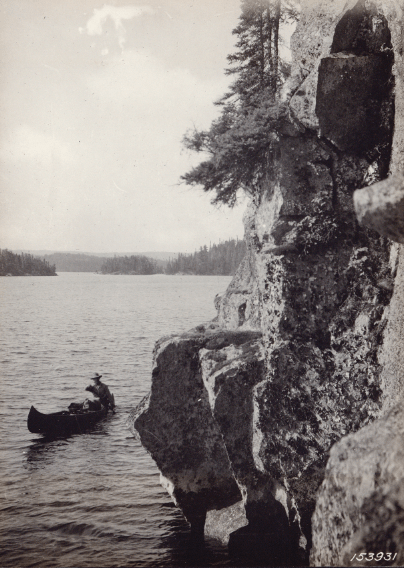

In our last issue, Wilderness News published photos from an album uncovered in an attic trunk. They once belonged to Big Bill Wenstrom, who was the last private landowner to leave the Boundary Waters Canoe Area when it became a wilderness in 1964. His family guessed that the photos of canoeists dated back to the 1940s. But thanks to Wilderness News reader Lee Johnson, Forest Archaeologist for the Superior National Forest, we now know the pictures date back to the 1920s. Wenstrom was a Forest Service employee at the time, as was landscape architect Arthur Carhart, who took the pictures. The Forest Service hired Carhart to survey canoe country just as the agency was beginning to grapple with the best way to balance ‘quiet’ sports and timber interests. His report would be instrumental in the region’s protection as a roadless area.

“I was surprised that those photos had the five to six digit numbers [on the bottom],” Johnson told Wilderness News. “I thought we had the only copies.”

The numbers told Johnson that the photographs had been archived at the regional Forest Service office. They’re now housed at the Iron Range Research Center, which stores about 120 bankers boxes of archival matter for the Superior National Forest Service—maps, letters and photographs, some of which date back to the early 1900s. They catalog the creation of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness and include fifty to sixty photographs taken by Arthur Carhart.

Carhart was hired as a Forest Service employee in 1918, and while his service was brief—just a few years—his contribution to wilderness management in northern Minnesota is irrefutable. Together with forest Ranger Matt Soderbeck, he undertook took two 24-day canoe trips through Northeastern Minnesota in 1919 and 1921, with the intent of making a management recommendation to the agency.

Established in 1905, the Forest Service was still young, and new to outdoor recreation. As told in Saving Quetico Superior: A Land Set Apart, by Newell Searle, in 1915 Congress appropriated money for the agency to create a forest recreation program to keep up with the increasingly popular National Parks system. The Forest Service hired landscape architect Frank A. Waugh to recommend just how to do that, and he made three recommendations: “protect natural beauty and scenery; make recreation and forest use equal to timber production and grazing; hire a landscape architect to plan the use of human resources.”

That landscape architect was Carhart. Employed out of the Denver, Colorado office, he first left his mark near Trappers Lake, where the Forest Service was contemplating building summer homes and cabins. But at Carhart’s recommendation, the agency reserved what is now known as the Flat Tops Wilderness Area for recreation and quiet sports.

Carhart’s recommendations for canoe country were similar, suggesting the area be left for canoe recreation with a “reasonable belt of timber along the edge of the water” to maintain scenic beauty. Carhart submitted his report to the Forest Service in 1922, just as the region’s development interests came to a head.

And it’s true. Carhart didn’t stick around for what became the great roads debate. Funding for his position dried up, and he left the Forest Service. But according to Saving Quetico-Superior, his report and departure coincided with a nation-wide movement to build national highways. That movement resulted in money being set aside for the forest service to build roads in northern Minnesota, and cities across the north clamored to get in on the action. Three roads were proposed for the Boundary Waters to serve tourism and recreation: Ely to Buyck (what is now the Echo Trail) including a spur to Lac La Croix; an extension of the Gunflint Trail to Seagull Lake, and most controversial, a road to the north of the Boundary Waters that would connect Ely and the Gunflint Trail. But Carhart didn’t leave the scene without ensuring a successor of sorts to take up the fight for a roadless area in northeastern Minnesota.

According to Saving Quetico-Superior, he wrote a letter to Illinois landscape architect Paul B. Riis, urging him “to champion the cause because a fresh face could ‘use my lines of argument to a much better advantage than I can myself.’”

Riis accepted that charge, and became president of the Superior National Forest Recreation Association, modeled after Carhart’s San Isobel Recreation Association of Colorado, which had worked for the protection of Colorado’s Trappers Lake area. Lacking its own landscape architect, the Forest Service agreed to consult with Riis and the Superior National Forest Recreation Association as it developed roads and a management plan. But progress was impeded by public debate over the roads and a subsequent movement to increase the size of the National Forest. Finally, in 1926, after four years without any recommendation from the Recreation Association, the agency developed its own policy modeled largely after Carhart’s 1922 report.

U.S. Secretary of Agriculture William Jardine established 640,000 acres of wilderness area eventually called Superior Roadless Area. It divided the Boundary Waters into zones for automobiles, boats and canoes. Most of the area would be set aside for canoe travel, but motorized boats would be allowed on larger lakes along the international border. Cars would be restricted to areas with fewer lakes and streams, and homes and resorts would be built only where roads connected to the area. The road between Ely and the Gunflint Trail would not be built, and the only allowed developments would be waterway and portage improvements.

In many ways, the public debate over land management was far from over. Riis objected to the management of the plan, favoring fewer roads. A 1925 proposal by lumberman Edward Backus to dam parts of the Rainy Lake Watershed threatened to dramatically alter water levels in the Boundary Waters. New activists like Ernest Oberholtzer took up the fight until the passage of the Shipstead Newton Nolan act of 1930, which also echoed some of Carhart’s original recommendations. The Act withdrew all federal lands in the region from homesteading, prevented the alteration of natural water levels and prohibited logging within 400 feet of shorelines in the Superior National Forest—effectively putting an end to Backus’ plan. But the 1926 roadless policy signaled an important shift in land management—social and human uses became just as important as timber production. And as Johnson notes, Carhart’s recommendations led to “some of the first policy coming not from outside but from inside [the Forest Service], promoting the benefit of roadless areas for recreation. Knowing your readership I think it’s really important that the story of Carhart gets out there. Those photos are significant in what is now the Boundary Waters.”

Wilderness News can only agree.

The Iron Range Research Center in Chisolm, Minnesota curates archival matter for the Forest Service. According to Lee Johnson, Forest Archaeologist, that includes about 120 boxes of maps, letters and photographs. There are six or seven boxes alone of photographs dating from the 1900s to the 1960s, and all that information is public.

“There are a lot of books in there yet to be written,” as Johnson says. To find yours, visit http://www.ironrangeresearchcenter.org

For More Information about Arthur Carhart and the creation of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, the following resources are a good start:

Arthur Carhart: Wilderness Prophet by Tom Wolf

Saving Quetico Superior: A Land Apart by Newell Searle