His canoes are used as part of a wilderness experience that teaches respect and integrity to young adults.

By Timothy Eaton

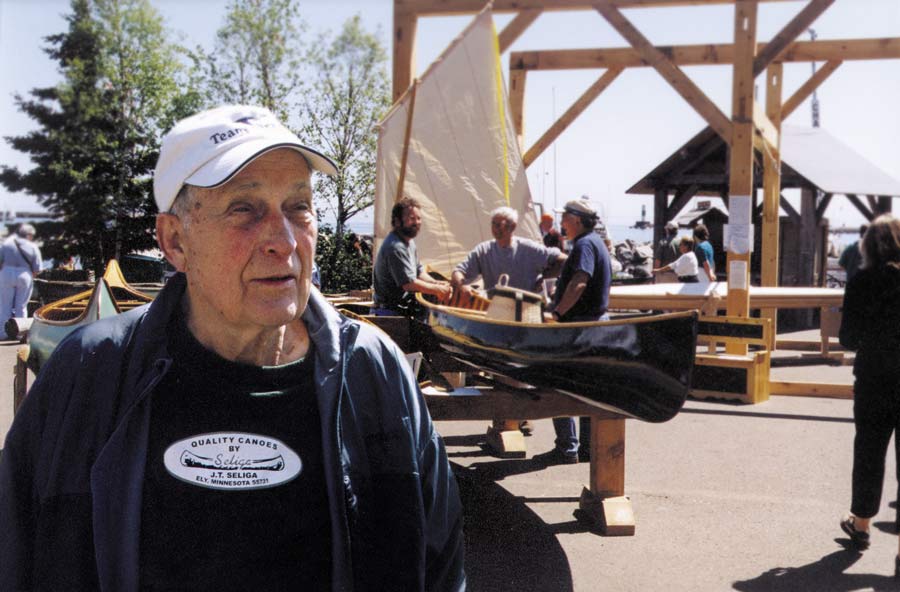

I had the pleasure of visiting with Joe on numerous occasions in the summer of 2003; first at the Wooden Boat Show and Summer Solstice in Grand Marais, again at the 5th Annual Canoe Rendezvous in Duluth, and at his canoe shop in Ely, Minnesota. Collectively, my visits attracted my soul to this delightful man— his humility, his love for his family, his interest in the occasional stranger, like myself, who wandered into his canoe shop and life. Most of all, I was attracted to his passion for life and the purpose for which he lived life—building wood-canvas canoes.

Joe Seliga grew up in the pristine Quetico Superior wilderness in the small mining town of Ely, Minnesota. When Joe was born in 1911, Ely was 25 miles from the nearest road. For the first thirteen years of his life the only way in or out of town was by train or canoe. The Seligas (mom, dad, Joe, and 11 brothers and sisters) were fortunate, they owned two Morris canoes. The canoes provided transportation, recreation, and their mobility to explore their wilderness surroundings, where they subsidized their lifestyle with fresh fish, game and wild berries. Later, these same canoes would inspire Joe to self-learn a trade— the art and craft of wood-canvas canoe building. Today, Joe Seliga is known and recognized around the world as the master canoe builder from Ely, Minnesota.

Their canoes

The Seliga family owned two canoes, a 15-foot and an 18-foot, both built by B.N. Morris. At the turn of the 19th century, B.N. Morris was the most respected canoe builder of the time. And his canoe company was located in Veazie, Maine. The Seliga family affectionately referred to the 18-footer as their “Veazie”.

Ely, Minnesota–1934

One of Joe’s favorite stories about canoeing with the “Veazie” took place in on an early spring lake trout fishing trip with his father, Steven. The water levels were high that spring. As they approached the lower rapids between Big Moose and Nina Moose Lakes all they could see was the wild spray of white water. Steven directed Joe to portage the gear around the rapids—he would run the canoe empty down the rapids. Joe recalled and remembered vividly the sound of ‘wood cracking’ over the roar of the river, when the canoe hit a deadfall on the way down the torrid and turbulent rapids with his father aboard. Joe dropped the packs and ran to the icy river’s edge where he pulled both his father and the canoe to shore. The “Veazie” would need repair—21 broken ribs. They were a long way from home!

Working together, Steven and Joe cut birch saplings. Using copper fishing line, they lashed the canoe back together and somehow managed to paddle the broken canoe back to town. Distraught by their misfortune, Joe lay awake at night thinking about the canoe and how to make permanent repairs. He studied the canoe’s construction. He experimented with bending wood and stretching canvas. Finally, after eighteen months the 21 broken ribs had been replaced and a new canvas cover had been applied. Their “Veazie” was as good as new and the family again had their beloved canoe. But most importantly, Joe and the family again had access to the wilderness experiences they loved and enjoyed.

A part-time business was born

Word got around of Joe’s success and soon he had a part-time business repairing wood-canvas canoes for others. By now the road into Ely had been built and with it came the fishermen, wooden boats and motors. In 1938, using their 15-foot Morris canoe, Joe designed a canoe form, and built his first canoe—a 16-foot square stern fishing canoe. He sold that first canoe the day it was finished. He built another, and another, and another. His part-time business turned full-time. But no sooner had Joe started than the U.S. entered the war in Europe. Suddenly, there was little time for recreation and little demand for his canoe boat. Materials ran scarce, and Joe returned to the local mine where he worked double shifts to support his young family. Consequently, he built no canoes between 1942-1945.

Building canoes for the camps

In 1948 Joe modified his 16-foot square stern canoe form and built his first double-ended canoe, which he called the ‘Scout’. He sold this canoe to the St. Paul, YMCA boys camp—Camp Widjiwagan. Upon delivery, the camp ordered five additional canoes. Then in 1949, Camp Northland, the girls YMCA camp, ordered 8 canoes which Joe delivered that year for a mere $36 dollars a piece—the cost of materials. He was back once again building canoes full-time.

From 1938 until the December 2005 day he passed away Joe Seliga built canoes—621 wood-canvas canoes. 237 of those canoes were built for the YMCA and church camps using the BWCAW and Quetico Provincial Parks. Joe Seliga is known around the world for his canoe building craft, but what many people don’t realize is how his love and respect for the canoe has touched so many young people’s lives.

The Widji Way

Camp Widjiwagan has a fleet of 100 wood-canvas canoes, and is one of just a few camps today that maintains the tradition of using wood-canvas canoes as an integral part of the wilderness experience. Teaching respect for the canoe, respect for one’s fellow traveler, and respect the wilderness, have been the hallmarks at Camp Widjiwagan since 1929.

“I have watched groups from Widjiwagan approach a portage. The canoe is unloaded while it floats, never touching land, the youth standing up to their knees in water, passing the packs to shore. When unloaded, the canoe is lifted from the lake, carried through the forest, and set down gently in the water. There is no noise, no grating of aluminum or fiberglass on rock, no telltale bits of ground up canoe on boulders to mark their passing. Even when one of the canoes is not wood, its treated with equal care. If all visitors to the wilderness took such care, it would be better for it.”

So writes author Michael Furtman in his book A Season for Wilderness (Northword Press, 1989) in the chapter entitled “The Widji Way.”

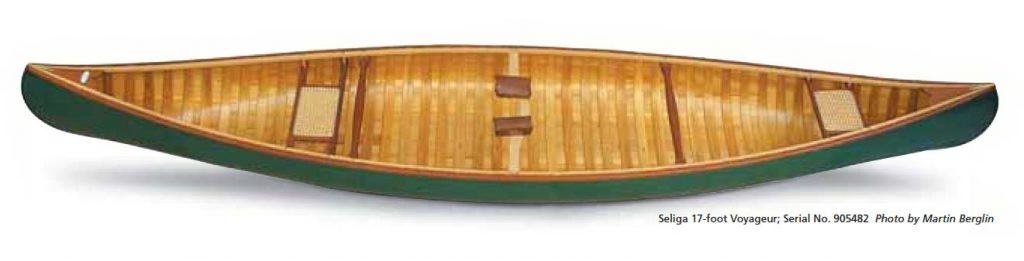

Widji was special for Joe

The camp used the Joe’s canoes as the experiential icon for teaching human and wilderness values. Joe cherished this notion and held a special place in his heart for Camp Widjiwagan. Before his death, Joe willed his two canoe forms and the Seliga canoe legacy to the camp. And, with the help of and generous gifts from individuals and friends close to Joe the camp created a one million dollar endowment to build a canoe shop, and fund the employment of a full-time craftsman to maintain the camp’s fleet of ‘Scout’ and ‘Voyageur’ wood-canvas canoes.

Widji makes a difference

“Widji is everything” Joe would exclaim.” If Widji makes a difference in one kid’s life it is worth every minute (of my time).” There was a permanent place set at the banquet table in the Widji dining hall for Joe. It was on Tuesday evenings, that campers returning from trail, would assemble in the banquet hall to share their stories and experiences of wilderness exploration and camaraderie. Joe rarely missed the opportunity to be present at those gatherings. At 92, when I interviewed Joe, he was very proud of the fact that two of his great-grandchildren had shared their Widji experiences with him on a Tuesday evening in the banquet hall.

Joe remembering his past

Joe loved to fish for lake trout. A boyhood experience he shared was the sight of his dad portaging their 18-foot ‘Veazie’ through the town of Ely with a pack on his back and their fishing poles in hand; Joe followed in toe. They were headed for Burntside Lake and a full day of lake trout fishing. “Dad would carry that canoe two miles through town to the shore of Lake Shagawa. From there, we had two more portages into Burntside Lake, which had the best tasting lake trout anywhere, short of my favorite fishing hole in the Quetico.”

Joe never did reveal this Quetico lake but at his memorial service one of his daughters filled me in on where it might be—along with a few of his ashes.

Embracing change

Over his 93 years, Joe Seliga saw many changes—to Burntside Lake, to the town of Ely, and to the BWCAW and Quetico Parks. “Of course I can see it now,” Joe acknowledged, “because so many people come here. You have to put on restrictions to preserve what’s here. And, I have been in favor of almost every change to protect this wilderness area. I was happy the day they banned the airplanes—they were too noisy. And, they should not have allowed the use of chain saws to clear the portages after the 1999 blow down—that was wrong.”

Joe Seliga, like Sigurd Olson, may have experienced the best of what we know today as the Quetico Superior—the BWCAW and Quetico Provincial Parks.

Joe’s book

On my last visit to Joe, I asked him about the notoriety that had come with the publishing of his book The Art of the Canoe with Joe Seliga by Jerry Stelmok. Joe’s reply— “I don’t know what all this fuss is about, I’m just Joe Seliga from Ely, Minnesota”.

Respect for canoes, respect for our fellow man and respect for the wilderness—these values epitomize Joe Seliga.

This article was published in Wilderness News Fall 2003