Originally published by the St. Croix Watershed Research Station, part of the Science Museum of Minnesota. Reprinted with permission.

You wouldn’t want to drink the water in some wild lakes on the largest island in the largest lake in the world.

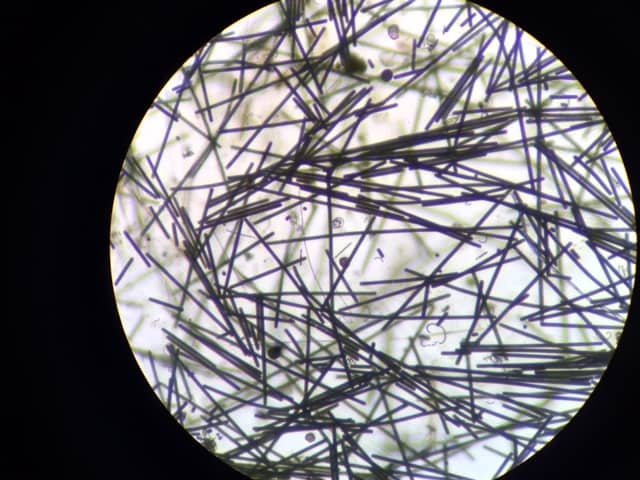

On Isle Royale during late summer, certain types of native algae (actually a kind of bacteria that converts sunlight to energy like plants) are potentially producing toxic chemicals that can sicken people and kill animals at high levels. While the toxins are diluted or not even produced at the algae’s typical low levels, big blooms have been known to fill a lake with poison.

Those blooms happen when the algae get more nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen, or something else changes in their environment.

But that shouldn’t happen on Isle Royale — the landscape is basically the same as it’s ever been. Or at least it doesn’t fit with what science understands about the connections between land, water, and these harmful organisms.

Confounding contamination

Isle Royale is a designated wilderness area and a national park, among America’s most pristine and protected places. It has not been logged recently, there have been no crops planted, no cabins built, and no wastewater discharged into the lakes.

Lakes respond to what happens in their watersheds, so the untouched waters of Isle Royale should be clean and pristine. But they are not. Research Station scientists and others have reconstructed the history of algae in northern lakes by looking at cores of sediment taken from their bottoms.

They have seen that the cyanobacteria blooms are becoming more common.

But they don’t know why.

Paddling, portaging, and probing for clues

In August, Research Station scientist Mark Edlund and colleagues launched a study on Isle Royale to help answer the question. It will build on previous work he and others have done on the ecological history and connections of these protected waters. They will analyze the history of eight lakes on the island, and continuosly monitor conditions.

The team successfully deployed an array of sensors and sampling tools during a two-week visit, which will provide hourly data about lake temperature, oxygen content, and more. Devices fashioned out of PVC pipes will collect samples of material in the water.

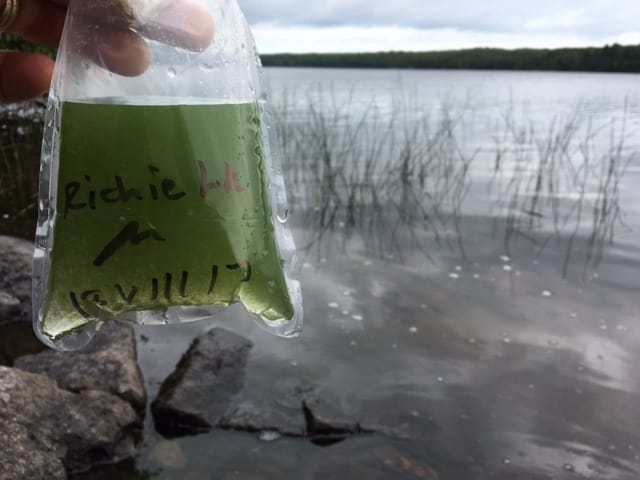

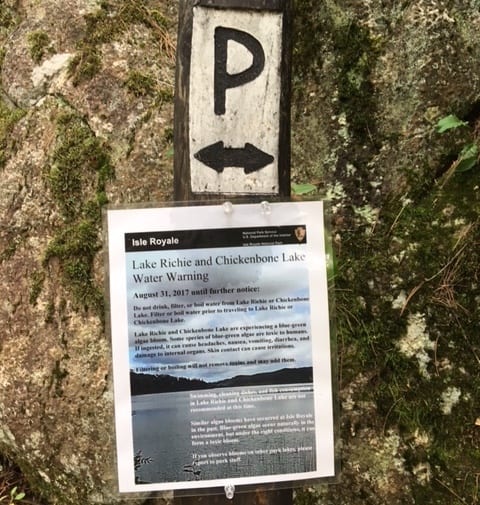

They also discovered two active blooms on Lake Richie and Chickenbone Lake. Partners at the National Park Service quickly posted warnings for park visitors to avoid drinking the water, swimming, or fishing in the lakes.

“It was the fastest I’ve ever seen our work affect federal policy,” Edlund says.

Weather and water

Warning people to stay out of the lakes and not to drink the water is one thing. Preventing such blooms is another.

It appears one reason Isle Royale’s lakes are getting more green is connected to climate change. Global warming can cause changes in temperature, wind, and precipitation, and lead to longer ice-free season and many inter-connected impacts.

But how and why climate change is driving the problem is a complex question, which must be answered before scientists and park managers can try to slow or even reverse the effects.

One theory is that warmer temperatures mean the lakes are staying stratified longer than before, with low-oxygen waters at the bottom absorbing more nutrients from the sediment. Or windier weather might mean the lakes are mixing together more frequently, bringing all those nutrients closer to the surface, where algae can absorb them, soak up sunlight, and reproduce.

The study Edlund and his team launched last month is part of the process of picking apart this problem. We’ll follow along with what they find. Subscribe here.

References: