By Laura Puckett, Wilderness News Contributor

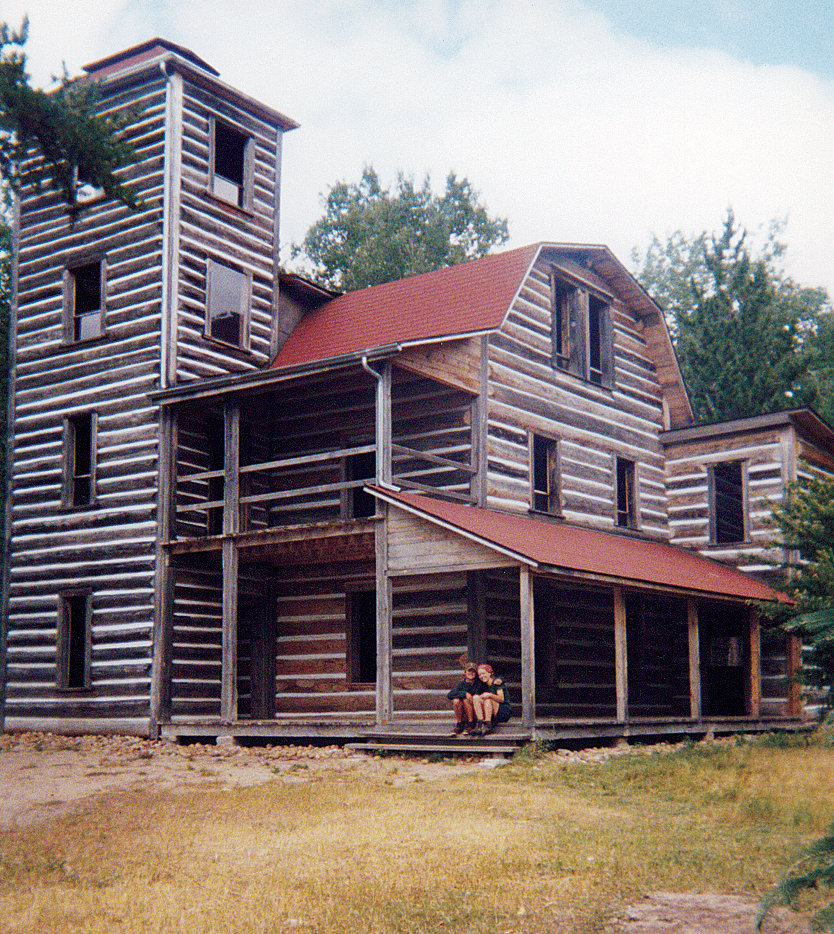

Paddling through the Crown lands of western Ontario the last thing a traveler expects to see is a castle, but there it sits on the shores of White Otter Lake, sixty-four kilometers north of Atikokan. White Otter Castle’s four-story tower rises amid the trees, adjoining a three-story main section and a two-story kitchen in back. The bright red roof and cavernous, sun-filled rooms are spectacular, but out of place, demanding the question: Why? Why such a grand effort, in the middle of nowhere, and by whom?

Jimmy McOuat was born in 1855 to Scottish immigrant farmers in the Ottawa valley. As the seventh child, he realized his chances of inheriting land were slim, so in 1886 he set out west on the new transcontinental railway and landed at Rainy River. By 1898 he had a successful farm, but like many at the time, he was lured into disaster by the few traces of gold found in western Ontario. Only two years later he was broke, trapping and looking for land.

Ever a homesteader, McOuat “hung up his hat” on White Otter Lake in 1903. He soon started work on his masterpiece: cutting, hauling, hewing, raising, and trimming more than a hundred logs weighing nearly a ton each, all by himself.

It is rumored that he even personally carried the windows, all twenty-six in their sashes, over the fifteen portages from Ignace. The walls were up and the roof was on in 1914, but Jimmy still

didn’t own the land. He tried to buy it from the Crown in 1917, and though they kept his money, they also kept the title deed. In 1918 he applied more strenuously, but before a decision was made he drowned netting fish; the proud builder of a monument, but not its possessor.

Perhaps it is because of McOuat’s unexpected death that White Otter Castle retains such an air of mystery. Myth maintains he built the castle to welcome a love who never arrived. Although he did once inquire after a mail-order bride, it was his refusal to go meet her family before she came west that led her to marry another. In Jimmy’s recollections, an angry blacksmith made a bigger impression. “Jimmy McOuat, ye’ll never do no good! Ye’ll die in a shack!” the blacksmith scolded, after being hit by a projectile corncob. It was in fact Jimmy’s friend who was the prankster, but the words rankled, and Jimmy swore to defy the blacksmith’s prediction. Clearly he did, but whether it was this grudge, the fundamental quest for a home, or the ambition to make his mark, McOuat’s motivations have been buried along with his body on the shores of White Otter Lake.

In the end it was a blessing the land remained property of the Crown. It was thus protected from mining in the 1930s. The castle received haphazard repairs by the Department of Lands and Forests in the 1950s, and in 1989 was protected again as part of a new park, Turtle River Waterway. The Friends of White Otter Castle Inc. was formed in 1986, and instigated a major restoration of the Castle from 1992 to 1994.

The detailed history is from “White Otter Castle,” by Elinor Barr (Thunder Bay: Singing Shield Publications, 2003). For more information about the Castle, The Friends of White Otter Castle can be contacted at P.O. Box 88, Atikokan, Ontario, POT 1CO.

This article appeared in Wilderness News Fall 2006