“As I drive along, contemplating the intricacies of life, the car gives a gasless sigh. It is 15 degrees below zero, and it is midnight. I’ll cover the last three miles the old-fashioned way, by placing one foot ahead of the other.”

So begins Justine Kerfoot’s book Gunflint.

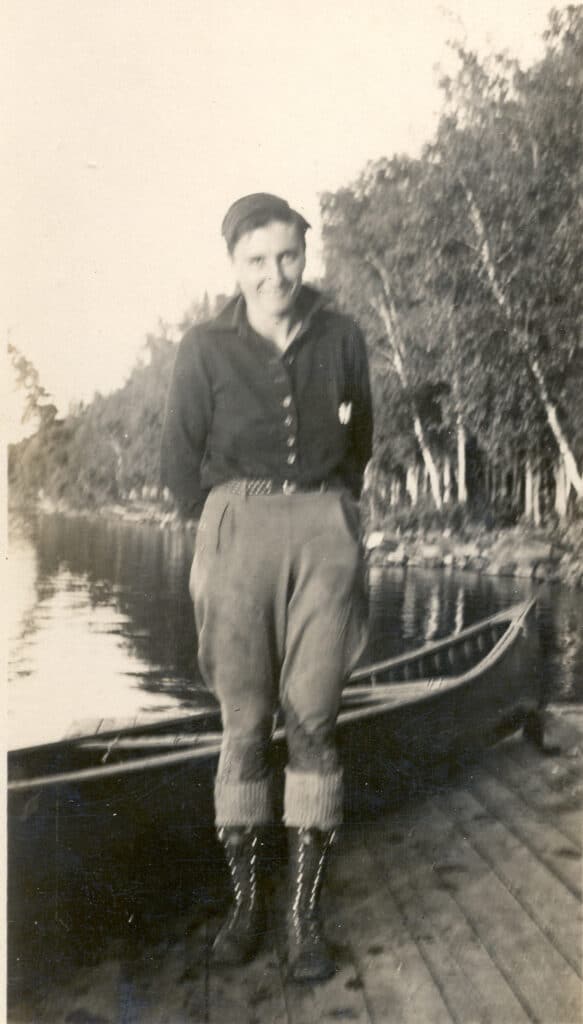

Justine Kerfoot spent most of her adult life on the Gunflint Trail, from just before the Great Depression until her death in May of 2001. During her time there, she accomplished many things and witnessed life in the region evolve and change. Her legacy lives on today, although not all know her story.

In 1927, Justine had received her undergraduate degree in Zoology from Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. Her goal was to continue on there, with graduate studies leading to becoming a doctor. Her parents had purchased a fishing camp way up in Northern Minnesota on the Gunflint Trail called the Gunflint Lodge. During that summer, her mother asked her to come up and help run the lodge. At the time, there were three cabins for rent, a main lodge with dining room and store, and a lot of work to be done.

Justine was raised in the city, with no real training in all the things that she quickly became proficient in. The lodge itself was reached by going about three quarters of the way down a gravel road from Grand Marais; just over forty miles of twisty, hill and valley driving through deep woods. Like most resorts in the region at the time, the Lodge was not served by plumbing, or electricity, or telephone service. Those amenities would come over time.

In August of 1929, their world changed with the beginning of the Great Depression. Justine’s parents lost their property in Barrington and their second home in Lake Zurich in Illinois, hanging onto the Lodge as their now primary residence. Medical school was no longer in the picture, and Justine quickly started to learn the ways of the woods. Simple things like using the trees and hills on the shore as guides while canoeing around the lakes. How to paddle a canoe, and portage that canoe from lake to lake over paths. It’s worth noting that canoes haven’t always been made from Kevlar or aluminum; in the 1930’s, canoes started the season weighing about seventy pounds, and by the end of the summer, topped out at over one hundred pounds as the cedar absorbed water. She learned how to guide guests of the lodge on fishing and hunting trips, make sure they were safe, and brought home fish and game. As she says in her book Woman of the Boundary Waters:

“I don’t know when, but the fact remains that I did fall in love. An infinitesimal speck in the cosmos, I stood on the shore of Gunflint Lake beneath a great white pine-matriarch of a fast vanishing tribe. And I knew I was home. I was twenty-one. The year was 1927.”

Over time, Justine became friends with members of the Ojibwe Tribe in the region, including Tempest Powell Benson, Lillian Ahbutch “Butchie” Plummer, and Charlie Cook. They furthered her education in living in the northwoods, in all the seasons, lessons that served her well.

She tells the story of a Native American from Grand Portage who stopped by the lodge one day to pick up supplies. He didn’t have money with him at the time, and agreed to leave some beaver pelts as collateral, a normal practice for many in the region. In this case, however, the U.S. Customs agency discovered them while searching for a smuggler, and the pelts were confiscated; Justine didn’t have a permit for trapping.

She was charged and brought to trial. She might have gotten off if she had explained the circumstances; by doing that, however, she would have betrayed her customer and tainted her reputation with Native Americans and other neighbors. She pled guilty to having the hides in her possession, and was fined $300 by the judge. It was a huge sum of money at the time; the judge gave her probation and suspended the fine.

Running a lodge in the woods required other skills as well. Daily life involved gathering firewood, building cabins, providing first aid, acting as a midwife, putting docks in and taking out, maintaining canoes and boats, and later plumbing, wiring, servicing telephone lines, small engine repair, and more. Justine did all of these things, and while she may have been nervous about it, she did what needed to be done, whatever the task. In reading her books, she was proud of what she had learned and accomplished, but not because of her gender. Rather, because she got each job done, and done well.

She had a reputation for being resourceful, if a bit ‘cantankerous’. A 2019 article of the Star Tribune quotes Justine: “If you had half a brain, you could sort stuff out”.

One lasting contribution that Justine and her neighbors made to the region was introducing new fish to the lakes in the region. According to Steve Persons, the Area Fisheries Supervisor for the Department of Natural Resources, the lakes in the Boundary Waters region were populated by Lake Trout and Northern Pike. During the 1930’s, Justine would pick up milk containers that had been shipped up to Grand Marais, filled with Walleye and Bass Fry, and distribute them to lakes and streams on the way back to the lodge. Since all of the lakes seem to be connected to one another, the introduction took hold and spread. Walleye and Bass are now part of the fish population.

Winter in the deep northwoods is not for the faint of heart. Justine learned how to travel by dog sled across the lakes and trails in the region. The Trail itself was difficult to travel during nice weather, and did not improve when snow started flying. She tells the story of getting stuck in deep snow and having to shovel her way out, moving the car twenty five feet at a time. As the years passed, snowmobiles replaced dog sleds and brought new challenges.

Lake ice was harvested and kept in ice houses for cooling food and beverages throughout the rest of the year. Sawdust was used to insulate the ice, and the neighbors all helped each other cut blocks from the lake and store it. Picture a grid on a lake in late December or early January, hand saws, pry bars and tongs, dog sleds moving loads to the ice house, and hard work for everyone.

During the Christmas celebrations held at the Lodge for the neighbors, she recounts watching guests cross the ice and snow covered lake from the warmth of the lodge. They were times of celebrating friends and the intangible gifts those friendships bring.

Over time, the region became increasingly popular with tourists. Amenities in one resort pressured other resorts to improve their facilities, and the road improved, along with improved telephone service, rural electrification, plumbing, and more. A spirit of collaboration with neighbors continued to evolve, so that the unique character of the area was maintained. The Gunflint Lodge burned down in the early 1950’s and through the assistance of friends and neighbors, was rebuilt in quick order. She tells the story of rebuilding the fireplace and learning how to split rocks. It will make your hands ache just reading about it.

Justine and her husband, Bill, raised a family at the lodge, sending the kids off to school in Grand Marais, and later to colleges around the country. Over time, the marriage ended, but Justine stayed on the Trail.

In 1958, Justine started writing a column for the Cook County News-Herald which detailed life on the Trail. A collection of those stories is assembled in her book Gunflint, which divides the book up by months. If you’re looking for a deeper understanding of what life was like for residents of the region, you’ll be enthralled with her books. Reading about the changes throughout the year is a lovely way to whet your appetite for a trip to the Trail.

“Sparsely located as we were, there developed within us an unspoken, hidden concern for a neighbor’s safety. This feeling, call it what you may, permeated the fiber of the people who lived in this remote area for a long time. We gave help with no thought of being repaid by trinkets—whether beads, shells, coins or some other means of exchange. Help was given as a mutual means of survival in a demanding and often uncompromising environment. It was an exchange where deep within one’s soul resided an element of trust in the other.”

– Justine Kerfoot, Woman of the Boundary Waters

More Information:

‘City girl’ Justine Kerfoot becomes a North Woods Icon, Star Tribune

Betty Powell Skoog and Justine Kerfoot, A Life in Two Worlds, Savage Press, Superior, Wisconsin, 2010

Justine Kerfoot, Woman of the Boundary Waters, University of Minnesota Press, 1986

Justine Kerfoot, Gunflint, Pfeifer-Hamilton Publishers, 1991

Anne Queenan is a writer/photographer/video producer who reports on natural heritage, watershed health and land stewardship. She and her dog Coda live on the Mississippi River in Minnesota where she enjoys paddling, birding and scenic hiking.