By Alissa Johnson

The Quetico-Superior region of Minnesota and Canada bring to mind lake country—a landscape characterized by glacier carved lakes filled with clear, cold and clean water. Yet the list of possible impacts on northern Minnesota water quality is long: proposed mining, climate change, invasive species, nutrient loading, and algal blooms to name just a few. In some places, like Lake of the Woods, evidence suggests that changes are already under way. The open water season is 28 days longer than it was during the 1960s, and public concern over algal blooms helped prompt water experts to rethink how issues are monitored. Yet even where water quality remains unimpaired, studies are underway, forming what some scientists call a defensible baseline—an understanding of what’s currently happening in the region so water can be protected in the future. Here’s a look at three studies underway:

Algal Blooms Help Spark Plan of Study

Algal blooms on Lake of the Woods have been getting a lot of media attention in recent summers. Area residents and visitors seem to disagree on whether the severity of the thick green slime is getting worse, but the 2014 Rainy-Lake of the Woods State of the Basin Report identifies the blooms as a significant concern. And Nick Heisler, Senior Advisor with the International Joint Commission (IJC)—an international organization charged with protecting waters along the Canadian and United States border—says that public unease helped drive the creation of a Plan of Study for the area.

“Basically, the public became aware that water quality is not as good as it used to be and said, ‘We want it restored,’” Heisler said. As public concern grew, the premiers of Manitoba and Ontario asked the Canadian government to get involved, which in turn asked the IJC to evaluate the governance of water quality in the Lake of the Woods basin and prioritize water quality issues. Of course, that wasn’t a simple task. Factors like climate change, the presence of heavy metals, and aquatic invasive species all factor into the state of the basin, not to mention the fact that several different government and non-governmental entities have a stake in the watershed. Lake of the Woods occupies parts of Minnesota, Ontario, and Manitoba, which mean that one state, two provinces, and two national governments are involved. And until recently, two different IJC governing boards monitored water quality and water levels in Lake of the Woods.

According to Heisler, the IJC combined the boards and expanded its physical geography to include the entire basin, which is nearly 27,000 square miles. This new board began meeting in 2013, made up of an equal number of Canadians and Americans and, for the first time, an equal number of government and non-government individuals. In order to prioritize issues, the board updated the State of the Basin Report and identified several key concerns: algal blooms and algal toxins; climate change; nutrient loading; surface and ground water contamination; water levels and erosion; and aquatic invasive species. The knowledge gaps—the information they didn’t have—formed the basis for an International Lake of the Woods basin Water Quality Plan of Study.

“It creates a blueprint for a study that would then identify specific causes, solutions and remediation,” Heisler said. The IJC released a draft of the plan in July of this year. It recommends 32 different projects with a total estimated cost of $7,228,000 to address five major areas: water quality monitoring and information gathering; nutrient enrichment and algal blooms; aquatic invasive species; surface and groundwater contamination; and international water quality management. The Study Team has recommended three options to fund the study, which fund varying degrees of the study. The IJC is collecting public comment on the plan of study’s funding options through mid-December, after which the IJC will make recommendations to the governments of the United States and Canada to restore the quality of the water in the Lake of the Woods Basin.

“The big goal is identifying the knowledge gaps and helping both jurisdictions know what the other jurisdictions are doing. There is no point in one setting a whole section of parameters while the other jurisdiction does nothing,” Heisler said. (Review the study at http://www.ijc.org/en_/LOWWQPOS).

The Envy of the Nation in Watershed Monitoring

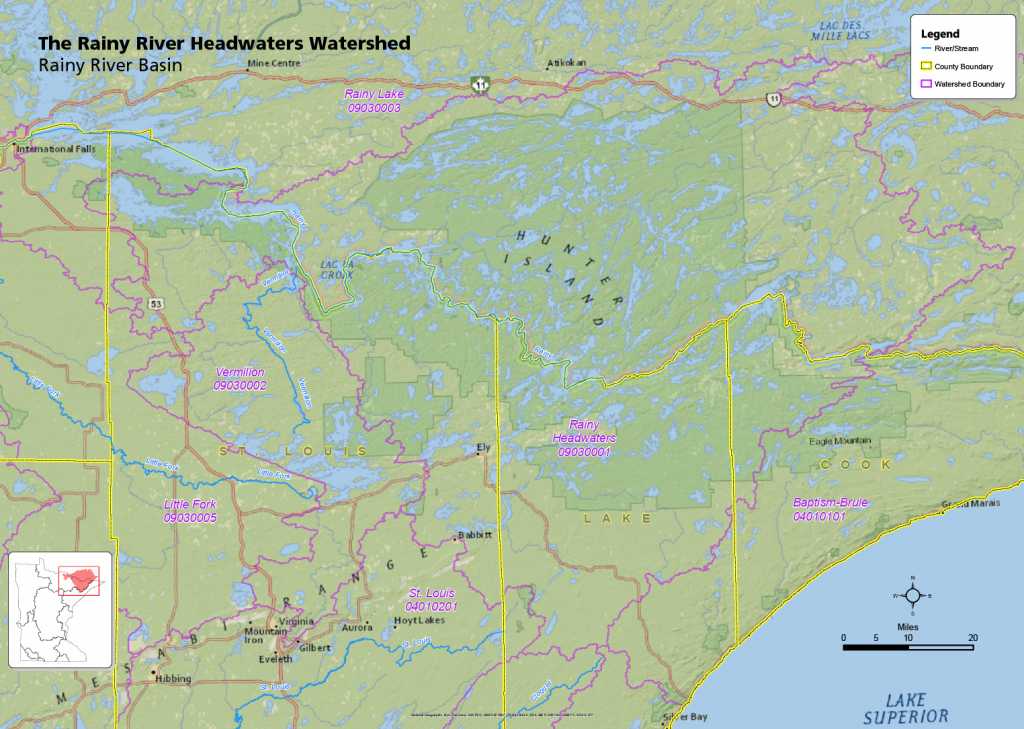

This sumer the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) completed the first of two years of intensive watershed monitoring in the Rainy River Headwaters Watershed—a tall order considering that the necessary equipment includes batteries weighing 50 pounds apiece and much of the watershed lies beyond the reach of motorboats. It includes most of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, almost all of Voyageurs National Park, and all of Quetico Provincial Park.

“We know that overall the water quality is very good,” said Joel Peterson, MPCA Watershed Ecologist. “But there are a lots of things to look at.” He explained that the MPCA was looking at water flows, contaminant loads at different rates of flow, and the variation between different parts of the watershed among other data. The information will help the MPCA model the impacts of potential contaminants and development in the area.

“We’ll get a very defensible base line—the general understanding of what’s going on,” Peterson said. “And if we do develop around a lake and start seeing changes in that baseline, and we can attribute it to what we’re doing on land then we can fix it. We’re obligated to fix it by federal and state law.”

Funding for the project comes from the Clean Water, Land and Legacy Amendment passed by voters in 2008. The Amendment increased Minnesota sales tax for 25 years, and the “Legacy Dollars” directed toward water quality make it possible for the MPCA to up the ante when it comes to water monitoring across the state. In the past, the agency surveyed about 1% of the state’s 81 watersheds each year and used a narrower approach to monitoring. If there was a problem with turbidity, Peterson says, scientists studied turbidity—even though there might be other factors at play.

“We started calling it the 100-year plan because it was not effective,” Peterson said. Now, the MPCA surveys about 10% of watersheds each year and uses a more holistic approach. Teams survey the water for the biota present, and if it doesn’t match expectations, they conduct a stressor identification process to determine the cause. It’s a more holistic approach to monitoring that has made Minnesota the envy of the country among water monitoring experts and agencies. It’s an exciting time for watershed ecologists, made even more exceptional because of inter-agency partnerships.

“We’re actually talking to each other across federal and state agencies. Part of it is because (with the wilderness area, a provincial park, and a national park) it’s such an exciting watershed to work in that people are more willing to share and want to protect it,” Peterson said. A water quality report is expected this winter.

Provincial Park, and almost all of Voyageurs National Park. Map courtesy of the the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency.

Understanding the Impacts of Mining

The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) is about a third of the way through a three-year study designed to understand metal concentrations in areas that could be mined. According to Perry Jones, USGS Hydrologist, the USGS set aside funds to look into the impacts of potential mining.

“We decided that if we’re going to look at the impact of future mining, we have to understand what the background concentrations are in the watersheds,” Jones said. To do that, the agency is assessing the influence of natural copper-nickel bedrocks in the Duluth Complex on water quality. The team has been collecting water samples and monitoring stream flow in Filson Creek and Keeley Creek near Babbitt, and on the headwaters of the St. Louis River near Hoyt Lakes.

“The objectives of our study are to assess copper, nickel, and other metal concentrations in surface water, rocks, streambed sediments, and soils in watersheds where the basal part of the Duluth Complex is present, and to determine if these concentrations are currently influencing regional water quality in areas of potential base-metal mining,” Jones explained.

A geochemist is also collecting bedrock samples and soils in the parent glacial material to understand how the composition of the glacial material and the rock relates to the chemistry of the water. The goal is to provide information that regulators and mining companies can use in development and assessing mining proposals. Jones said the study’s findings should provide valuable information for both mining companies and regulators.

“From our standpoint, we’re collecting scientific data,” Jones said. “That gives an unbiased credibility to our data because we don’t have objectives. I think that will help the mining companies as well as the regulators in their evaluations.”

Read more in Wilderness News Fall-Winter 2014