One of the wolves from a 2018 relocation project escaped Isle Royale crossing the ice to Canada, and was tracked by GPS as she wandered thousands of miles across Ontario and northern Minnesota.

In 2018, the National Park Service and partners began capturing wolves on the mainland, in Minnesota, Ontario, and Michigan, and releasing them on the island to start rebuilding the population. The wolf population on Isle Royale in Lake Superior started shrinking in 2006 and, over the next decade, the animals nearly disappeared. The National Park faced a rapidly growing moose population, which threatened to overrun the island ecologically without natural predators.

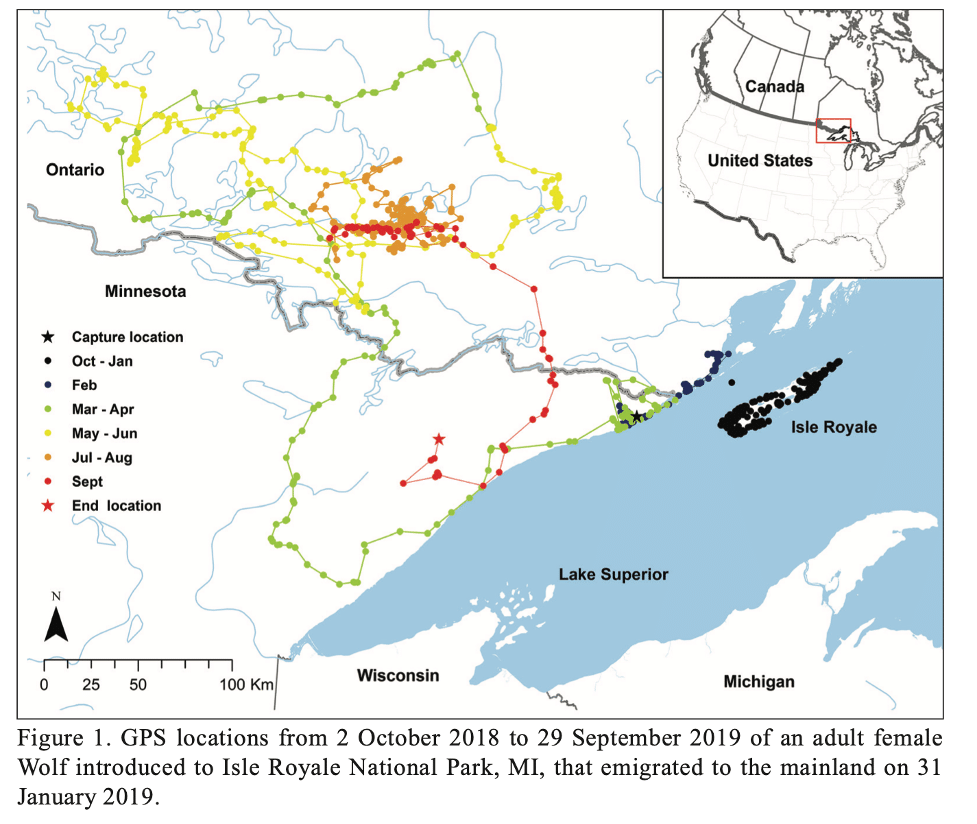

The third wolf in the project was released in the southwest part of the island, near Windigo, on October 3, 2018. A nearly 70-pound, four-year-old female, she had distinctive black coloring on her back. Dubbed 003F, she spent the next few months criss-crossing the archipelago, getting to know her new territory — or possibly looking for a way to escape.

A recent scientific paper shares the story of this enigmatic animal on an incredible journey.

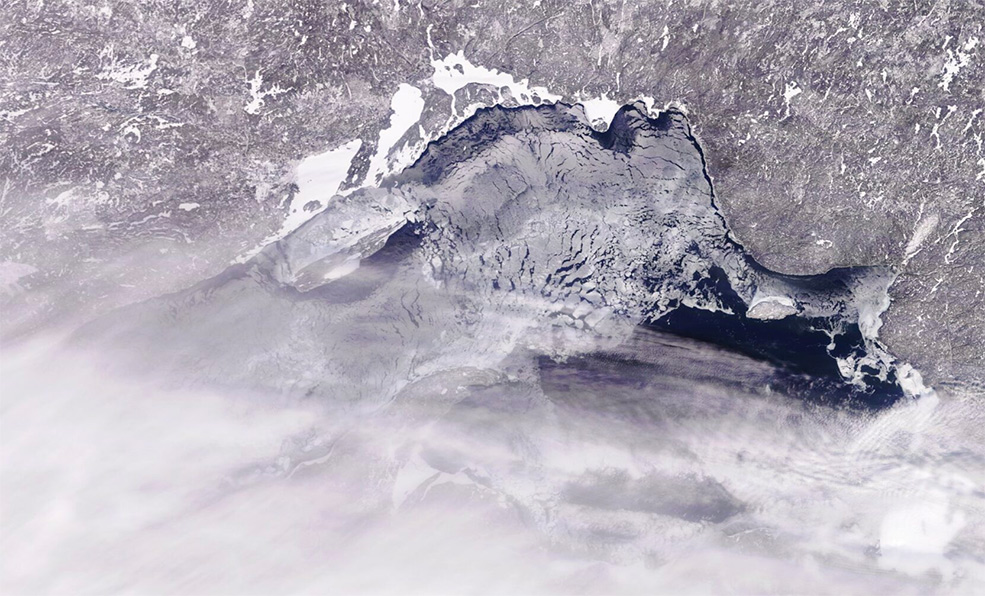

In the middle of January 2019, the Polar Vortex arrived. Furnaces were strained and car batteries groaned. In the last week of the month, temperatures at nearby Grand Portage bottomed out each day at 15-25 degrees below zero Fahrenheit.

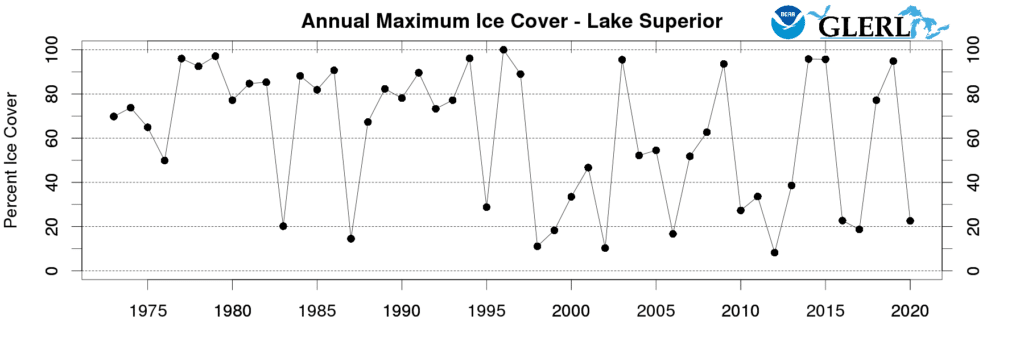

Lake Superior started icing over, which doesn’t happen often.

As the Polar Vortex continued in February, Lake Superior nearly iced over entirely. But Wolf 003F didn’t need to wait that long. By about Jan. 26, there was ice connecting Isle Royale to the North Shore of Lake Superior.

The wolf saw her chance, and she headed home.

The ice provided a bridge to cover the more than 15 miles of water between Isle Royale and the North Shore. She left the island on Jan. 31 and started crossing.

Ice bridges are believed to have been how wolves first reached Isle Royale in the 1940s, but climate change has made the formation less frequent. It’s one reason wolves had not naturally repopulated the island, and why the National Park Service took drastic steps to help.

For a project that had been years in the making, the loss of a study subject was a setback to scientists. But it wasn’t a surprise.

“Nature and the instincts of wildlife will always prevail in the wilderness of Isle Royale,” park superintendent Phyllis Greene said at the time. “When we made the decision to restore the predator-prey relationship, we knew we would have to respectfully work with whatever curves nature threw at us, whether it’s adverse weather or wolves working out where they choose to fit on the landscape.”

Researchers suggest many reasons for braving the ice – it could have been getting harder to live in peace on the island as the new wolves began competing for food, packs, and breeding. Perhaps she was homesick, or just not ready to settle down yet.

Still wearing a tracking collar, which provided her location by satellite, the research team kept an eye on 003F, while bringing more wolves to the island. Meanwhile, the wolves that she had left behind were pairing up, establishing new packs and territories.

Wolves are not encumbered by international borders, and 003F took advantage of her freedom. She first reached the mainland on the Canadian side, and soon returned to where she’d been captured months before, on the Grand Portage Indian Reservation in the United States.

But she didn’t stay there, either. Wolf 003F ended up spending the next year on a wandering tour of the region, crossing back over the international border at least two more times.

“She continued traveling around Minnesota and into Ontario, Canada, until deciding to remain in Ontario from July to September 2019,” the study reported. “From September to October 2019, wolf 003F ventured back to Grand Portage Reservation (in Minnesota) for a month. This stay was brief before she traveled back up to Ontario. Although she has spent most of her time in Ontario since October 2019, she did make two excursions to Voyageurs National Park in Minnesota during February and March 2020.”

There is no way of knowing if this was her habit before being captured and transported to Isle Royale. Biologists and veterinarians who examined her before release said they believed she had had pups at least once before, so it’s possible she had once been part of a pack.

But Wolf 003F also seems to like to travel. The GPS collars have allowed scientists to study the daily movements of wolves, and found that she regularly covers nearly 1.5 times the daily distance as her counterparts back in the island.

There is also no way of knowing how she will spend the rest of her life. Her GPS collar quit transmitting her location at the end of last year. Wolf 003F is once again an anonymous predator, wandering the canoe country wilderness.

More information:

- Wolf that left Michigan’s Isle Royale has had amazing 2-year journey, GPS data shows

- Wolf Departs Isle Royale on Ice Bridge, Feb. 6, 2019 – National Park Service

References:

Elizabeth K. Orning, Mark C. Romanski, Seth Moore, Yvette Chenaux-Ibrahim, John Hart, and Jerrold L. Belant “Emigration and First-Year Movements of Initial Wolf Translocations to Isle Royale,” Northeastern Naturalist 27(4), 701-708, (16 November 2020). https://doi.org/10.1656/045.027.0410