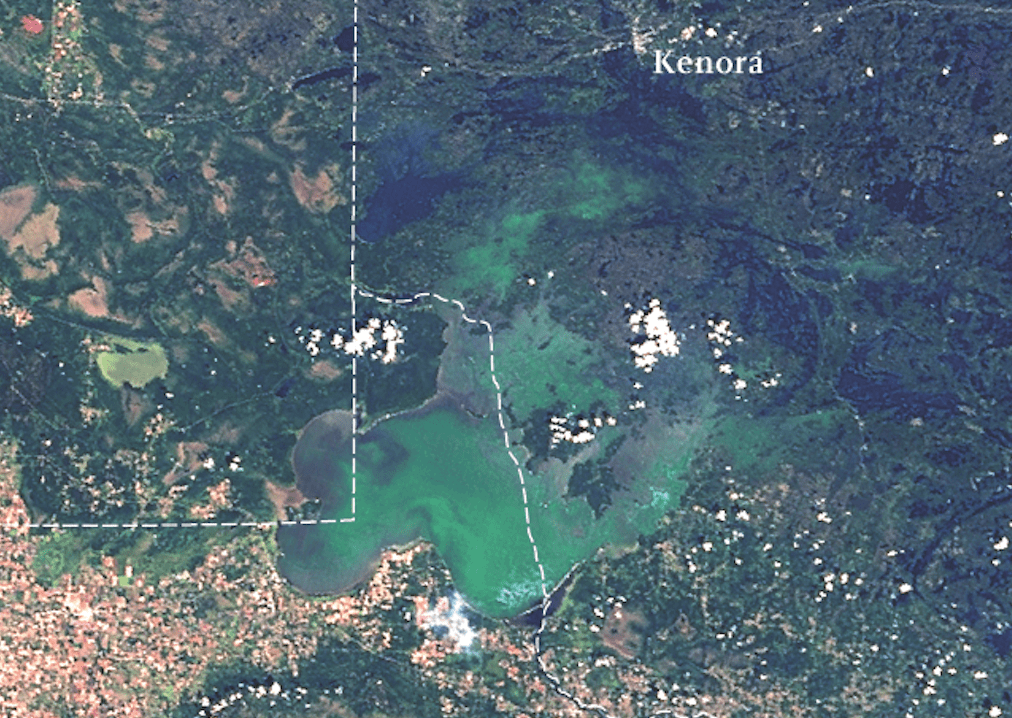

Photo courtesy of Jonathan W. Chipman, Space Science and Engineering Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

By Charlie Mahler, Wilderness News Contributor

In early 2008, when the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency releases its updated list of impaired waters in Minnesota, it is likely that Lake of the Woods, the massive 950,400 acre lake on the state’s border with Ontario, will make the inventory due to nutrient impairment. If so, Lake of the Woods would become the first border area lake to make the list in that category.

Steve Heiskary, a research scientist for the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, told attendees of the recent Lake of the Woods International Water Quality Forum in International Falls that he was “inclined to put Lake of the Woods on the draft list” to be submitted to his agency later this year. The comprehensive list includes not only nutrient-impaired waters too rich in phosphorous and nitrogen, but also those exceeding thresholds for oxygenation, turbidity (cloudiness due to disturbance), mercury, and fish consumption.

In a February 2007 Office Memorandum Heiskary wrote for the MPCA’s Rainy River Basin Planner Nolan Baratono, which was distributed at the International Falls meeting, Heiskary noted that data collected in the summers of 1999, 2005, and 2006 showed the lake exceeding nutrient threshold values for phosphorous (one year), chlorophyll-a (two years), and transparency (all three years).

The likely inclusion of such a well-known, large northern Minnesota lake on the listing of nutrient-impaired waters, draws attention to the fact that even northern lakes with watersheds composed of largely wild country can suffer eutrophication (an excess of nutrients which cause dense plant life growth) problems not unlike water bodies in more southern agricultural areas. More broadly, the concerns about Lake of the Woods point to the importance of water quality issues even in seemingly pristine areas like the Quetico Superior.

The Lake of the Woods Watershed

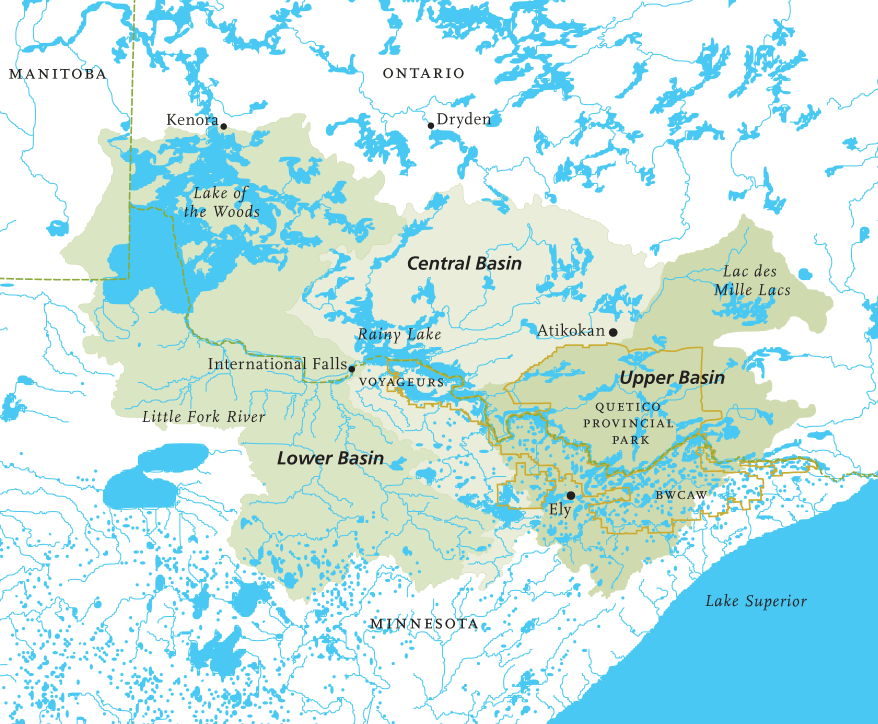

The Lake of the Woods watershed, or Rainy River Basin, comprises 27,114 square miles of drainage area shared by the United States (41%) and Canada (59%). Its boundary approximates a rough-edged rectangle of land and water from just northwest of Lake of the Woods to just northeast of the north shore of Lake Superior. The northern edges of the area roughly parallel the international border a hundred miles to the north. Its southern frontier snakes west from above the north shore for a hundred or so miles, before turning northwest toward Lake of the Woods.

The headwaters of the basin include extensive areas of Canadian Shield topography in wild areas including the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness and Quetico Provincial Park. Northern Minnesota waters not flowing into Lake Superior through the north shore and waters not part of the St. Louis River watershed drain into Rainy River and Lake of the Woods. In Canada, the upper portion of the basin begins as far east as Lac des Mille Lacs and includes waters south of the drainage divide

rising between Atikokan and Dryden.

The central portion of the basin in Minnesota is characterized by a collection of large lakes, including Crane, Kabetogama, Namakan, Rainy, and Vermilion, some of which make up Voyageurs National Park. Waters from the corresponding section of the drainage on the Canadian side enter the large border lakes at Namakan Lake via the Namakan River. (See Namakan River story on page 6). As in the upper basin, the topography here is largely Canadian Shield as well as isolated areas of glacial materials.

In the lowest segment of the drainage, waters in Minnesota flow into the Rainy River or directly into Lake of the Woods through the extensive wetlands located on the Glacial Lake Agassiz lake bed. Some of the watersheds in this segment include those of the Vermilion, Little Fork, Big Fork, and Baudette Rivers. In Canada, the waters flowing directly into Lake of the Woods cross mainly shield geology. The waters gathered at Lake of the Woods flow on for another thousand miles, ultimately to Hudson Bay.

The MPCA’s Baratono differentiates water quality concerns within the basin in light of these geographical differences. “Basin-wide, the primary issue is protection of aquatic resources,” he said. “However, if you look separately at the upper basin (Rainy Lake and its watershed) and the lower basin (below Rainy Lake) there are some differences. For the upper basin, the primary issue is protection. The water quality of most of the streams and lakes in the upper basin is good to excellent.”

“In the lower basin,” Baratono continued, “while protection is still important, there are many restoration needs. For example – excluding toxics like mercury – all of the basin’s impaired waters are in the lower basin. We’re also concerned about erosion, nutrient over-enrichment, and dissolved oxygen concentrations.

The 70 mile-long Little Fork River, in the lower basin, makes the state’s list for its turbidity problems. Surprising perhaps, especially to those unfamiliar with fish consumption advisories, is the long list of BWCAW lakes that are listed as impaired for mercury and its attendant concerns. From Sea Gull to Thomas, from Snowbank to Crooked Lakes, even the wildest lakes of the region are less than pristine by that measure.

Caring for the Water

The MPCA’s 2004 Rainy River Basin Plan, which was developed under the authority of the federal Clean Water Act, outlines the breadth of likely problems within the watershed. It describes the measures in place and proposals to monitor, protect, and restore water quality. The plan is a product of the collaboration of dozens of county, state, and federal agencies that are responsible for the health of the waters of the region.

The Lake of the Woods International Water Quality Forum serves as an annual information-sharing meeting of researchers, stakeholders, and agency officials in the region. It is sponsored by Rainy River Basin Water Resources Center, the Lake of the Woods District property Owners Association, the North American Lake Management Society, Rainy River Community College, the Ontario Ministry of the Environment, and the MPCA.

Most striking in the comprehensive Basin Plan and in the research presented at the Forum, are the myriad factors that can impact water quality in the region. From concerns about vacation property septic systems and lawn care regimes, to the expected advent of sulfide mining in the basin, there seems no end to the ways the watershed could be compromised.

In the more pristine upper basin, monitoring efforts – often in partnership with local communities and lake associations – seek to closely observe conditions around the watershed to spot potential issues before the problems occur.

Across the watershed, including the wildest upper reaches, mercury still remains a persistent problem. Larry Kallemyn, who has studied mercury in fish in Voyageurs National Park for some 30 years, analyzed trends in his presentation at the Forum. While he found fish mercury levels varied year-to-year – controlled by factors including atmospheric deposition, surface water level variations, and the abundance of certain large fish prey species – he concluded that levels were not decreasing and likely were still increasing thanks to the continued input of mercury from atmospheric source and remobilization of the element already deposited on the earth.

Exotic invasive species are also a cause for concern in the watershed. Last year, for example, spiny water fleas – tiny crustaceans with long, sharped barbed tails that originate in Europe – were found in Rainy and Namakan Lakes in Voyageurs National Park. In an effort to keep the animals from infesting the smaller “interior lakes” of Voyageurs on the Kabetogama Peninsula, park officials are currently considering banning anglers from carrying live bait

into the smaller lakes, banning the movement of boats from the infested lakes to the interior water bodies, and prohibiting private planes and boats in uninfested lakes, according to media reports.

The Little Fork and Lake of the Woods

On the turbidity-impaired Little Fork River, problems appear to stem from post-settlement forestry practices in a sensitive watershed. At the 2006 Forum, the MPCA’s Jesse Anderson presented research that concluded “numerous symptoms on the landscape indicate that the river has destabilized.” He cited excessive stream bank erosion, the incised shape of the stream channel, and the presence of perched culverts and small tributaries down-cut at confluence with the Little Fork which indicated a lowered main channel.

Anderson’s research suggests that historic, basin-wide logging caused more water to run into the river more quickly without vegetation slowing

the run-off. Additionally, trees felled in the area in historic times were floated down the river to milling sites, destabilizing the channel as they bumped and bashed their way downstream. Anderson traces the turbidity impairment on Little Fork to sediments released from erosion of the unstable channel at high flows of the river.

Sometimes, however, the various factors – natural and human-caused – that affect water quality

are more difficult to untangle. The vast, varied, and downstream Lake of the Woods, which may make the impaired list in 2008, is one such case. Algal blooms, some of which include toxic blue-green algae, or cyanobacteria, appear to have increased in recent years there. But just how much of the apparent increase is due

to increased shoreline development and other human factors, and how much is part of the natural regime is still a question in search of answers.

The lake has been long known to have had significant algal blooms. Records through the 1800s note algal blooms on Lake of the Woods. As early as 1823, Major Joseph Delafield, the agent for the American survey team tasked with settling the boundaries between the United States and Canada, noted that on Lake of the Woods, “The islands were numerous and crowded, the water shoal and foul, frequently with a green scum of vegetable matter.” A proposal in 1883 for the city of Winnipeg to use Lake of the Woods for its drinking water supply was objected to because of, “…deposits of green vegetable

matter” in the lake.

“Cyanobacteria blooms on Lake of the Woods are a large concern,” the MPCA’s Baratono said, “however we have limited data for Lake of the Woods. The MPCA is monitoring Lake of the Woods water quality to see if the lake is experiencing nutrient over enrichment. At this time we don’t have the data to determine the causes of the cyanobacteria blooms.”

It is the unenviable task, then, of the 21st Century researcher to disentangle the factors affecting today’s waters. Questions still left unanswered despite recent focused study on Lake of the Woods include: whether higher water temperatures and acidity and periodic low dissolved oxygen in the lake prompt a recycling of phosphorous from the lake bed, whether or not there has been an increase in phosphorus discharge in the basin due to increased development, whether the reported increase in frequency of cyabobacterial algal blooms can be mainly attributed to phosphorus concentrations.