1909 was a significant year for the Quetico Superior region of Minnesota and Ontario. Before the well-known legislation of the 1930s that officially designated the roadless areas and parks that we know today, an important foundation was laid—on both sides of the border, in the very same year.

The Quetico Superior region was not always as we know it—managed, regulated, and clearly defined. It was once territory open for exploration, and vulnerable to exploitation.

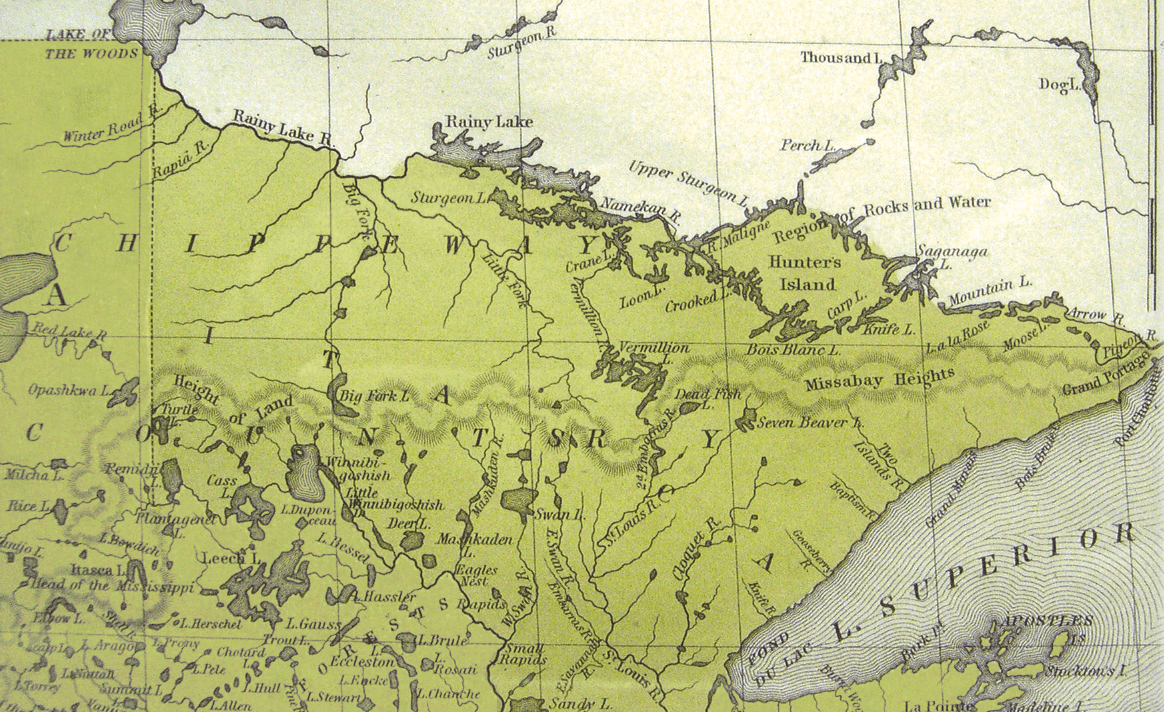

The rapid industrialization of the 1900s fostered demand for raw materials, lumber and minerals; and for many it was a time of prosperity. Roads were built, railroad tracks laid, and it seemed westward and northward expansion could only bring a better life for all. With increasing accessibility to transportation, and to satisfy the thirst for building materials, the lumber industry logged large swaths across northern Minnesota and the Canadian border. Prospectors rushed into the uncharted wilderness seeking gold, ore and other minerals. In addition to logging and mining, trophy hunters streamed into the northern ‘frontier,’ hungry for big game.

While industrial growth spurred the turn-of-the-century economy, the cultural beginnings of a ‘wilderness ethic’ emerged. Fueled by a desire to escape the polluted cities, and return to a more idyllic time in America, people began to value the outdoors as more than a well of raw materials. For locals, the beauty and rarity of the northwoods was not an imaginary ideal, but a daily reality. Fearing a decline in moose populations and total depletion of the forests, citizens on both sides of the U.S.-Canadian border took action.

Efforts In the U.S.

In the early 1900s, General Christopher C. Andrews, Forestry Commissioner of Minnesota, arose as a champion for preservation—he laid the foundation for Chippewa National Forest, and then turned his attention to the Minnesota Arrowhead region. He successfully petitioned the Federal Government to withdraw land from settlement, resulting in 3 separate allocations of land between 1902-08. General Andrews urged his counterparts in Ontario to follow suit.

Efforts In Canada

As the possibility of logging and the threat of overhunting in the Quetico forest loomed, several voices emerged in favor of a forest and game preserve: Ernest Thompson Seton, writer and naturalist, William Alfred Preston, Member of the Ontario Legislature for Rainy River, Arthur Hawkes of the Canadian Northern Railway, and Aubrey White, deputy minister of Lands and Forests. Their efforts, both independent and coordinated, included securing a promise from the province that Quetico would be saved if the United States also participated.

Vision Becomes Law

On February 13, 1909, President Theodore Roosevelt signed Proclamation No. 848 officially designating the land as the Superior National Forest—an area of approximately 1,018,638 acres.

The ‘Quetico Forest and Game Reserve’ Order-in-Council was signed on April 1, 1909—comprising 1,148,000 acres; land which would become Quetico Provincial Park four years later. The Order-in-Council said that Quetico was “to be preserved and set apart as a public park

and forest reserve, fish and game preserve, health resort and fishing ground; for the benefit, advantage and enjoyment of the people of Ontario, and for the protection of the fish, birds, game and fur-bearing animals therein.”

In a time when their international borders were in dispute, both countries joined in a common spirit to protect the landscape. A few visionaries spoke out for this area, valued it for its natural qualities, saw potential for tourism, and envisioned that both could be managed for perpetuity. In 1909, the Canadian and U.S. governments answered the call for preservation.

Now, nearly one hundred years later, how will we honor the landmark cross-border efforts that established the precedent for wilderness protection? 2009 represents an opportunity to celebrate the first hundred years and renew our commitment to the Quetico Superior region for another century.

— By Kari Finkler, Wilderness News Contributor

This article appeared in Wilderness News Spring 2007