There is peace – or at least a cease-fire – in one of Minnesota’s longest-lived environmental and land-use conflicts. Leaders from Voyageurs National Park and the city of International Falls, two entities at odds with one-another since Minnesota’s only National Park was established in 1971, are not only talking politely and genuinely to each other, but also making plans to partner for the long-term.

In a community where conflict over the Park had led to a grinding enmity between townsfolk who bristled at what they considered the Park’s condescending attitude toward them and where Park employees often felt the sting of resentment as they lived and worked in the community, conflict over the 218,000 acre National Park has mellowed. And, while the widely-respected Park Superintendent whom many in the city cite as critical to the recent changes has just retired, the city is set to break ground on a new headquarters building for the Park which it hopes will ultimately spur renewed interest in the Park and in the city of 6,700.

As improbable as the events might seem to people who have followed the decades of hostility between townsfolk and the National Park, word had trickled out of “The Nation’s Icebox” recently of a change in tone between the Park and the community. International Falls, it appeared, had come a long way since the acrimonious Congressional hearing held there in 1995 where residents, environmentalists, government officials sniped at one-another over the future of the Park in the ‘Falls’ high school gymnasium.

tipping point for the Park and the region.

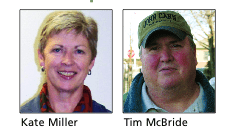

Proof of the new relationship between the Park and the community – and fond words for Miller – is now in evidence across the city.

In the local paper’s farewell to the Superintendent, the International Falls Daily Journal cited, “Miller’s leadership style and empathy for the experiences of many local residents” as allowing her to “set the standard for superintendents of Voyageurs National Park.”

International Falls Mayor Shawn Mason termed what Miller achieved with the community in her short stint as the head of the Park as, “…nothing short of a miracle.”

Even City Councilor Tim “Chopper” McBride, who once co-hosted, with Koochiching County Commissioner Wade Pavleck, a provocative snowmobile drag race adjacent to the Park and who termed himself a leader of the town’s “common-sense radical fringe,” volunteered that he will miss Miller.

Somehow, after more than 30 years of acrimony and tension surrounding the Park, much of the rancor and animosity between the town and the park melted into the northern Minnesota soil.

“She’s an incredible person,” McBride said.

A Change in Tone

The beginning of the change in tone surrounding the Park appears to have come from small, genuine gestures on the part of leaders on various sides of the park and town divide.

“Kate Miller, when she came onto the scene, I was very suspicious of her,” Mason admits today. But the mayor also recalls how she and Miller slowly got to know each other, at the town’s Curves fitness center. At one point, unbeknownst to one-other, each had nominated the other for a free spa-pampering contest sponsored by the establishment. “There was this mutual respect which I found very intriguing,” Mason said.

Still, when Miller invited Mason to attend a National Park Gateway Communities Conference in Shepherdstown, West Virginia, the mayor declined. “I didn’t want to go,” Mason confides. “I told people it was my schedule, that I had two small children at home and I just couldn’t go. But the truth of it was, I just thought it would be a waste of time.”

“There’s this hesitancy on the side of a local person who just really couldn’t believe what they were hearing,” Mason offered. “Go all the way to the East Coast to get brainwashed by the Park Service! I just didn’t trust the motives of it. I

wasn’t ready.”

Mason, however, did think enough to send her City Administrator to the conference, which was also attended by County Commissioner Pavleck. In the end, the Shepherdstown conference proved instrumental to the new town/park relationship. Pavleck would return with a changed attitude toward what the Park could mean for the community.

Outreach

On a separate track, Councilor McBride’s warming to the Park and its top official came after Miller, not yet the Park Superintendent, reached out to him after he shared a story of his family’s relationship with the land and the Park at an economic summit meeting hosted by Mason. McBride told of his family’s presence in the area dating to 1895: how one of his great-grandfathers had come to the area in a gold rush; how another great-grandfather had witnessed gunfights in Rainy Lake City; how other members of his family had traded with the Ojibwa residents of what is now Black Bay.

“I told a story about how I felt,” McBride remembers, “and it seemed to impress upon Kate. I got down to the fact that as a little boy, I wasn’t mad that the Park was here, but my dad was. Not mad, but he was concerned. But, that I was proven wrong by my dad – more and more and more restrictions, no economic impact, no marketing, more regulations on fish – followed the establishment of the Park,” McBride said.

Not long after McBride told his story, Miller became the acting Superintendent of the Park. “On her first day on the job,” McBride recounts, “she called Wade and I, and we met her at the Park Headquarters. And, I’ve never been so impressed in my life.”

“She didn’t make promises,” McBride notes, “but she made sure to tell us that she was going to do everything in her power to break those walls down – those communication walls, the fortress mentality the National Park had.”

Indeed, local officials don’t point to changes in Park policy so much as note changes in tone that Park officials – starting with Miller at the top – took when addressing local leaders and citizens.

“A lot of local people felt leadership, primarily Superintendents, didn’t look at us as good stewards,” Mason said. “They looked at us as – I hate to say this because I don’t want to offend anybody – looked down there nose at us as uneducated, as not having as much passion for the land, as they did.”

A Desire to Work Together

“I had two goals when I applied for the Superintendency,” Miller remembers, “and one was to do everything I could to turn around the relationship, not just with International Falls, but with other communities along the Park as well. One of my two real reasons for wanting to be Superintendent was that I saw an opportunity and a need.”

Miller, a Minnesota native who believed, “if you’re nice to people, they’ll be nice to you,” made her advances toward community leaders with a clear intent to better relations not just for local residents but for her Park employees as well. If local residents had felt the sting of condescension in the tone of Park officials, Miller herself knew the strain Park employees worked under in a community where many people resented them.

“The staff felt beleaguered after years of living and working in a community where they felt uncomfortable even wearing their uniforms into the grocery store,” Miller noted. “And, having either their kids in school or themselves in social circles, clubs, and churches have to fend off hostile questions and comments, even from their friends and family.”

Miller agreed that making “human to human” connections broke the ice between town and park, but stressed that the progress made in recent years is truly rooted in common values.

“When I heard Chopper speak so passionately about his and his family’s attachment to Rainy Lake and the land that is now part of the Park and the waters, I just knew we had a common core of values. So many of the people who were angry with the Park shared a deep, deep desire to protect it and preserve it for their children and grandchildren. We were just on such different wave-lengths about it.”

Miller made a concerted effort to build bridges toward leaders she thought could readily see the upside of working with the Park. “My philosophy from the beginning was to work in the middle. To work, not with the fringe aspects, not try to change people’s minds there on the fringe, but work with the people who could effect change and who were willing to move toward a more positive and productive relationship with the Park,” she admitted.

Miller has a special respect for the courage it took Mason, McBride, and Pavleck to step forward regarding the Park. International Falls was a town, Miller noted, where business owners often avoided supporting or promoting the Park for fear of boycotts by local customers.

“Absolutely it took courage,” she emphasized. “I admire them as leaders. They stepped up; they took a risk, but they believed it was the right thing to do. They’ve had tremendous influence. And, what their leadership did – Wade and Shawn and Chopper – was make it possible for the silent ones to relax and exhale and come forward and get involved in some of these projects.”

A Change in Approach

A decision made nearly five years ago and hundreds of miles from the Park may have also aided the harmonic convergence of factors that allowed stakeholders in the area to see their shared values rather than their perceived differences. In the first half of the decade, Voyageurs National Park Association (VNPA), an advocacy organization based in Minneapolis, decided

to modify its own approach to influencing issues regarding the Park, choosing to eschew, when possible, confrontational means.

“The Board here hired a consultant to look into the future of Voyageurs National Park Association and the role it plays in the park,” VNPA’s MacNulty explained. “At that time, the board really decided to shift gears a little bit

and try to work in a more positive way with the local communities.”

An organization better known around International Falls for its lawsuits regarding wilderness designation in the Park and protection of federally endangered timber wolves and bald eagles, took a more cooperative tact. “I would call people up, MacNulty said, “and they’d go, ‘What, you want to hear what I have to say?’”

MacNulty and VNPA, though, are still careful about getting too far ahead of community sentiment during these sensitive times. “How much we are publicly involved with things, is something we’re still navigating,” she admitted. “There’s still some resistance to the community working that closely with the Park. And there are still people who view Voyageurs National Park Association as this extreme environmental group, which we really are not. So we still have to be careful.”

One way that MacNulty and VNPA are working publicly with the gateway communities is through newly created Destination Voyageurs National Park (DVNP), a non-profit effort initiated by Mason to better market the Park to potential visitors. MacNulty serves as the chair of the DVNP board.

MacNulty sees the more agreeable tone in the Park’s gateway communities as vital for successful promotion of the under-visited Park. “When what’s in the paper is always controversy, controversy, controversy, it doesn’t make people go, ‘Oh, that’s where I want to go on my vacation!’ It doesn’t create a very welcoming atmosphere,” she noted.

“VNPA’s goal is to support the Park,” MacNulty stressed, “but also to protect and promote the resources. That’s why we’ve been focusing on these relationships, because I think they really speak to the long-term protection of the resources and moving beyond this era of controversy we’ve been in.”

“On the other hand,” she says, “we’re also very clear that our ultimate mission is to protect the resources of the Park – it matches the ultimate mission of the National Park Service. If it means disagreeing on something, we will, respectfully, disagree. And if it means, someday, using litigation we will use litigation, but it’s certainly not going to be the first tool we pull out of the tool chest.”

A New Spirit

The most tangible evidence of the new spirit in the area should soon grace the shore or Rainy Lake on the east end of town. There, the city plans to erect a new Voyageurs National Park Headquarters and Voyageur Heritage Center, which would develop a neglected strip of waterfront and provide a public-sector anchor for an adjacent lodge and convention center.

“This Heritage Center is very important,” Councilor McBride stressed. “It really is the heritage of this area – the voyageurs, the Métis, the routes, the aboriginals. My family dealt with aboriginals in 1895. That’s the history of this area.”

While funding for Voyageur Heritage Center was left out of this year’s state bonding bill, city officials are hopeful funds for that portion of the project will ultimately be secured, perhaps from federal sources.

A late-summer ground-breaking for the Park Headquarters, 2,000-seat Irv Anderson Amphitheatre, and the walking and biking trails portion of the project is expected once the National Park Service Director and the federal General Services Administration sign off on

the project.

The new Park Headquarters building will be owned by the city, built to suit the Park Service, paid for with revenue bonds, and, after the bonds are paid, rent that the Park Service pays on the building will flow directly into city coffers.

The Voyageur Heritage Center, Miller noted, was initially conceived by Minnesota House Speaker Irv Anderson, of International Falls, as a way to “spite” the Park – co-opting the “Voyaguers” label but not inviting the Park to participate in the endeavor. When the project resurfaced in the new atmosphere – and with the Park in search of a new headquarters – it morphed into the partnership between the city and the Park.

“Our regional office has gone from great skepticism to wholehearted support,” Miller said of the project. “They’ve just been so impressed by how the community earnestly and diligently pursued this. That kind of commitment cannot occur in an environment that is not trusting and where there aren’t some strong mutual goals.”

“We’re going to build that Park Headquarters,” McBride asserted, “and that is an unbelievable partnership.”

Sustainable Change

Miller’s recent retirement, however, hangs a question mark over the durability of new peace. Are the good feelings between the Park and community sustainable without one of the persons critical to their initiation? The current quiet period could prove to be a mere blip in the acrimonious history of the Park and the local community. On the other hand, it could endure and act as a model for other gateway communities and Parks – or even Ely and its wilderness area.

That the détente is founded not so much on policies, but rather on the respectful attitude of the last Park Superintendent and the courage of a handful of elected officials could be a cause for concern. Miller, though, is hopeful. “I really believe it can [endure],” she said. “Sometimes it takes the initiative of one or two people. Having overcome some of those first communication and relationship hurdles, it’s gone beyond relationships. I think it’s becoming institutionalized in a way that takes it beyond dependency on personalities. Yet, leadership style is always critical to keeping this thing on track. It’s still very sensitive.”

MacNulty, who considers the next few years critical to the relationship, questioned whether the “personalities” aspect of the new relationships was as critical as has been described. “I don’t know how much of that is really the center of the point, or if people were really looking for a change and this was a way to make the change,” she said.

Whether the new Park Superintendent, expected to be named this summer, will approach the community with a similar attitude is also a question. City officials and others keeping a close eye on the hiring say the Park Service is aware of the need to have leadership that will continue to nurture relations between city and Park.

Miller agrees: “I know the Park Service doesn’t want to go back. They will be very careful in selecting the next Superintendent, so that the work that’s been done will continue in the same vein.”

A derailment off the current track could come from the town side of the relationship too, of course. Some local residents still feel the sting on Park matters, still mourn cabins lost in the purchase of Park land, and are still distrustful of the Park Service. This fall’s municipal elections – where both Shawn Mason and Tim ‘Chopper’ McBride will stand for re-election – could change the city’s leadership on the issue. Pavleck, who stood for re-election to his County Board post last November, however, was re-elected handily.

“People will have an opportunity to have their say on it when Shawn and Chopper run for re-election,” Miller said. “I’m sure they’re anxious to know what the referendum on this question is going to be. I believe their leadership is supported with the exception of a few voices – a couple of them fairly influential. I really think the tide has turned.”

Factors and elements outside the common ground established by city leaders and the Park could also imperil the progress made. Litigation from an environmental advocacy group could underscore the differences rather than the similarities among local stakeholders. An onerous new policy from the National Park Service hierarchy could pit the Park against the community despite local efforts to the contrary. McBride himself stressed that a barbless hook fishing regulation on Park waters, which had been rumored in the past, would prompt him to vociferously protest.

Miller and McBride, though, are generally hopeful about the future. The out-going Park Superintendent even allowed herself to imagine the relationship, well into the future and in the sunniest light.

“I just think this community and the way this Park has preceded with it, could in fact, 15 years down the road, be some kind of a model, because there were thoughtful steps taken all along the way,” she said. “And, there were good results. It was intentional; it wasn’t accidental over a couple of beers after a meeting.”

“I think the team,” Miller said, referring to all the people who met in the middle with her, “could have something to offer to other communities.”

Editor’s Note: The Quetico Superior Foundation would like to applaud the leadership of Shawn Mason, Cory MacNulty, Tim McBride, Kate Miller, Wade Pavleck, and others for creating a cooperative spirit and bringing the National Park Service and the International Falls community together on a positive outlook for the future of Voyageurs National Park and International Falls.

By Charlie Mahler, Wilderness News Contributor

This article appeared in Wilderness News Spring 2008