What Global Warming Could Mean for the Boundary Waters

By Alissa Johnson, Wilderness News Contributor

Mention canoe country to any canoeist familiar with the Quetico Superior region, and an array of sights, sounds and smells spring to mind: the bow of a canoe cutting across a calm northern lake; the jagged relief of pine trees silhouetted against an evening sky; the curled bark of a birch tree; the aroma of pine duff warming in the summer sun. Even the most subtle nuances of the boreal landscape conjure emotional stirrings so deep it would be nearly impossible for many canoeists to imagine their canoe against the backdrop of a deciduous maple forest. Yet according to Dr. Lee Frelich, Research Associate and Director of the University of Minnesota Center for Hardwood Ecology, unchecked global warming could transform the boreal forest of Minnesota into just that. Or possibly, even, an oak savanna.

It’s hard to make a statement like that without gaining the sudden attention of every canoeing enthusiast in the region. The 1999 blowdown and the more recent Cavity and Ham Lake Fires have already created high profile change in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness and surrounding areas. Adding a more ominous threat in the form of global warming certainly heightens the discussion. Frelich would likely argue that it is not a separate conversation. All of it – the storm, the fires, an already changing forest – is deeply intertwined with global warming.

According to Lee it’s a common misperception to simplify the effects of global warming by blaming them solely on rising temperatures. In reality, increased temperatures are not going to directly cause the coniferous forest to die out and a deciduous forest to spring up in its place. Take, for example, the jack pine so common across the BWCAW. The species has populated the forest for thousands of years, and in so doing has tolerated the coldest winter temperatures and the hottest summer days. As Frelich puts it, even the tiniest twig on a tree isn’t all that affected by temperature.

It’s more appropriate to think about global warming in terms of the changes it creates in overall weather patterns, impacting conditions like temperature, precipitation, or storm activity. Changes in weather patterns can have big effects. Insects, bacteria or fungi might thrive where they were once absent, a factor capable of wiping out entire coniferous forests as the Mountain Pine Beetle has done in the west. Decreased moisture levels can lead to increased droughts that interfere with a tree’s ability to deal with stress. Trees under duress shut down secondary functions that aren’t critical to survival, like the production of compounds that make them unpalatable to insects.

Other changes in weather patterns can result in more days with high dew points, which in turn can result in more frequent severe storms. It only takes the severity of the blowdown to demonstrate the significance that could have for the landscape.

Each of these factors alone can have major consequences for any forest. But in the context of global warming, few changes happen in isolation; taken together, the potential for change only multiplies. Add to that the context of the Quetico Superior region, and they start to take on even greater significance. Canoe country is located on the southern edge of the boreal forest. The edge of any forest is prone to fluctuation as natural changes in climate conditions favor the species of one landscape and allow them to gradually take over those of the neighboring forest.

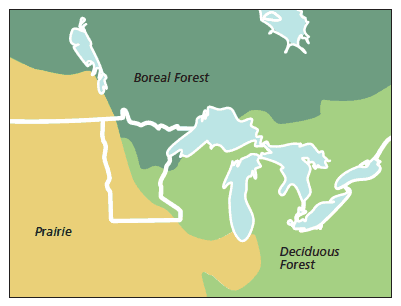

In Minnesota, the southern edge of the boreal forest yields to a deciduous forest that grows diagonally across that state in a narrow band from the northwest to the southeast corner. Below this deciduous forest lies the prairie. This naturally occurring distinction between coniferous forest, deciduous forest and prairie has been fluctuating for thousands of years. The significance? As climate conditions change more rapidly as a result of global warming, the region is inherently susceptible to change.

Frelich, having studied the BWCAW extensively through his work with the University, believes transformation is already underway. While deciduous trees are not unheard of in the BWCAW, a typical hundred-year old maple is stunted, only 15 – 20 feet in height, and bears frost cracks in its bark. In recent years, Frelich has found smooth-barked maples that are already 15 – 20 feet tall at the age of six, suggesting that milder winters are already impacting forest composition.

At the same time, where maples are found Frelich also sees worms. Worms are not native to North America or cold climates, and their invasive presence is an inauspicious harbinger of climate change. They alter the composition of the soil by eating the leaf litter, make it more susceptible to drought and facilitate the spread of invasive species. It remains unclear if maples and worms facilitate each other’s spread, yet their presence suggests to Frelich that warming would mean a gradual shift in forest makeup.

However, just as global warming can’t be seen only through the lens of temperature increases, these are not the only changes in play in the BWCAW. According to Frelich, the last several summers have seen more days with high dew points, creating conditions that can cause more frequent and larger storms. The predominant tree species in a boreal forest are not storm resistant. The characteristic tufts at the top of many conifers that make the Boundary Waters tree line so distinctive also make them top heavy. This point becomes especially poignant in light of the 1999 blowdown. A study completed by Frelich’s graduate students after the July 4th storm demonstrated that aspen and jack pine are the most likely to blow down, whereas maple, ash and birch are the least likely.

For a forest dominated by jack pine this has significant implications. Jack pine are fire dependent, requiring the heat of a fire to release their seeds every 20 to 150 years. The right fire will leave the jack pine standing but burn the forest understory, creating space and fertile soil for the released seeds to germinate. When fire occurs too frequently cones don’t have time to mature. When they don’t occur often enough seeds will be too old to germinate. In a landscape where jack pine have been felled by storms, their seeds are consumed by fire and the trees won’t regenerate. The Cavity Lake Fire of 2006, which burned a portion of the blowdown, has demonstrated just that. The jack pine are being replaced by birch, aspen and cherry.

This thought may send a collective sigh of relief through the hearts of canoeists, for what other tree could be more symbolic of the north than the paper birch? But all three species are susceptible to drought. With current global warming predictions that the middle of the country will become drier, this does not bode well for the future of northern Minnesota’s boreal forest.

If climate conditions continue to change unabated, Frelich believes they’re likely to be replaced by deciduous trees: a hardwood maple forest, or under drier conditions, perhaps even an oak savanna on shallow or sandy soils.

For Frelich, it all adds up to the veritable “fruit basket” upset. So many factors are in flux that without intervention it’s unlikely current forests will remain intact. Still, Frelich remains an optimist. If measures are taken to drastically reduce emissions of greenhouse gases and mitigate the effects of global warming, he believes it’s possible for the forests to remain intact. But if no action is taken, changes could happen in the next two to five decades, much faster than a typical forest evolves. Conditions will be ripe for invasive species like buckthorn to beat out the competition. The question will shift from whether the forest will change to whether it can keep up with the climate change and transition gracefully. For Frelich, a “graceful transition,” where a deciduous hardwood forest or an oak savanna wins out over invasive species, is the next best thing to keeping the BWCAW intact.

Whatever the outcome, the fate of the Quetico Superior region remains to be seen. Now, as ever, human impact will play a large role in determining that outcome. But talking with Frelich, it’s clear the rules have changed. What was once a matter of preservation without human interference now becomes inextricably intertwined with human intervention.

This article appeared in Wilderness News Summer 2008