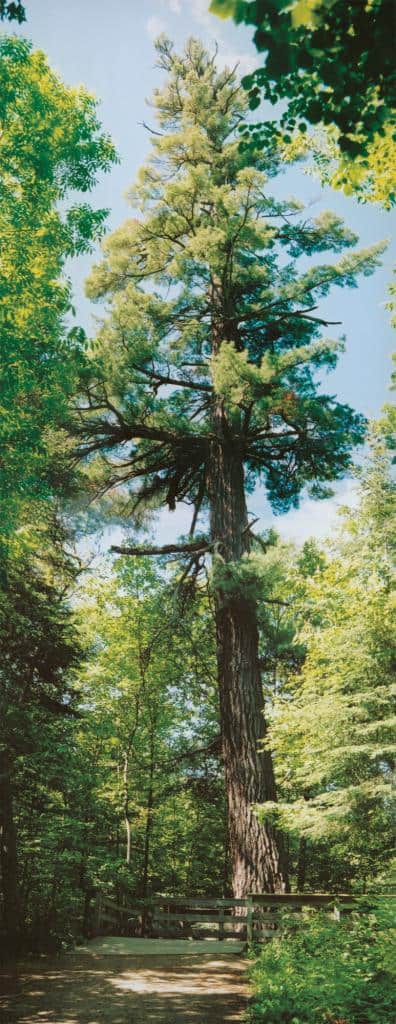

Bold against the sky, the feathery branches of an old white pine have a distinctive silhouette. Although not the most abundant species in the Quetico-Superior forest today, generations have strongly identified with the tree—an emblem of the natural resources that defined the region’s geography, economy, and character.

Perhaps that is why white pine became such a lightning rod environmental issue in the late 1990s. On one side of the debate the environmentalists were arguing that white pine had been decimated and needed protection. On the other side was the timber industry, hoping to cut white pine as freely as they always had. Then there was the government—the state legislature and public forestry agencies—who for years had ignored white pine, overwhelmed by how difficult it was to grow.

Environmental groups rallied behind the tree’s banner, challenged the reigning lumber barons, and took the state and federal foresters to task. Since then, public agencies have revised their management policies and Minnesota has gained more than 10,000 acres of white pine, but the question remains if the species really has a future, or are we simply in a pax pinus, in which the pine are doing well, so long as we don’t look too hard.

The Quetico Superior region

The forest was never blanketed with white pine, but it was a significant ecological and financial component, with emotional significance. White pine provides important species and age-class diversity—factors that help a forest weather natural disasters, such as climate change and pest infestation. They provide habitat particularly for eagles, osprey, and bears, but also pileated woodpeckers, lynx, a myriad of insects and fungi.

This ecological balance was upset when logging began in 1837 as people sought white pine’s strong, soft wood for construction and fine woodworking. Clear-cutting destroyed the canopy, eliminated seed sources, enabled a thick deciduous understory, and slowly, as the southern part of the state was settled and hunting became an industry, deer—which like to eat the new buds—spread into the northland. With the advent of overseas trade came invasive pests, and among them blister rust—a fungus that infects white pine needles and can kill the trees. New trees were not growing, and all the while, logging continued.

A call to arms

In 1990 Lynn Rogers, a U.S. Forest Service wildlife biologist, discovered that the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR) and the U.S. Forest Service were treating white pine essentially the same as the timber companies were: cutting and leaving. Instead of white pine re-growth, in its place appeared aspen and birch—species that spring up easily after a disturbance, grow quickly, and then make a good profit as pulpwood. The Forest Service’s own statistics said that only 2% of Minnesota’s original 3.5 million acres of white pine still existed, and yet they made few, if any, efforts to replant what they cut. Having seen how important white pine was as shelter for the black bears he was studying, and now realizing the magnitude of its disappearance, Rogers took to the streets. He spent the next six years campaigning for white pine through educational materials and lobbying congress. In 1993 he founded the White Pine Society and in 1996 he helped introduce the influential White Pine Act, with its controversial two-year moratorium on white pine cutting, which helped transform the DNR’s white pine program.

In the early 1990s white pine cutting continued rampantly. Even the Forest Service stressed the importance of white pine to maintain profits in timber harvesting. In 1995 the Sierra Club introduced the Restore the White Pine Act to the Minnesota legislature, including the cutting moratorium. The bill did not pass, but in response the DNR formed the White Pine Regeneration Strategies Work Group—which recommended the legislature take up stronger regeneration strategies, but few cutting restrictions. In 1997 the moratorium was reintroduced, but rescinded when the DNR agreed to notify the public of cutting plans, reduce cutting of mature white pines, and increase regeneration efforts. They made white pine a specific part of their agenda and increased communication with the public. Governor Arne Carlson and the state gave millions of dollars for white pine research, and the white pine movement was on a roll.

Simultaneously Minnesota’s forest management

policy was being revolutionized by the 1994 Generic Environmental Impact Statement on Timber Harvesting and Forest Management in Minnesota—an enormous collection of studies and recommendations analyzing how low, medium, and high harvesting scenarios would impact Minnesota’s forests. This seminal document led to the creation in 1995 of the Minnesota Sustainable Resources Act, and its offshoot, the Minnesota Forest Resources Council (MFRC). For the first time in Minnesota’s history forests were being considered on a broad scale—landscape and statewide.

Today the MFRC is working to cooperatively establish goals and sustainable standards for Minnesota’s forests. The state has been divided into eight landscape regions, each of which is represented by a committee of concerned citizens to coordinate forest management for that region. One of their purposes is to develop specific objectives for what they want their landscape to be in one hundred years. In North Central and Northeast Minnesota, the primary goal is to have a forest that “approximates/moves toward the range of variability . . . for plant communities naturally living and reproducing in northeastern Minnesota,” and specifically, to “increase the white and red pine component,” especially those over 100 years old. These legislative changes pertain to the state, but for its part, the U.S. Forest Service has made similar strides in its management of the Superior National Forest. The 2004 Land and Resource Management Plan for the Forest strives for “diverse mixes of trees, shrubs at site and landscape levels that are more representative of native vegetation communities,” with white pine as “a priority species.” The Forest Service oversees white pine nurseries, plantations, and research, striving to increase white pine acreage where appropriate and the number of old white pines in general.

These kind of specific goals and strategies have revolutionized the way forests are envisioned in Minnesota. On both the state (DNR) and federal (U.S. Forest Service) level, the public stewards of the land are developing clear goals for the future of Minnesota’s forests. Practically, however, they still must face the challenges of actually growing white pine in Minnesota.

How a seed becomes a giant

Policy changes have been essential in establishing a new perspective on white pine, but serious financial and time commitments are needed to bring the arboreal monarchs back. According to Lee Frelich, a forester at the University of Minnesota and a major contributor to the MFRC’s landscape program reports, white pine are not going to regenerate in Minnesota if we don’t manage the obstacles: insufficient seeds, lack of fire, smothering

deciduous growth, and hungry deer.

Jack Rajala knows the truth of these threats first-hand. As the owner of Rajala Companies, a forest products company near Grand Rapids, Minnesota, he is one of the loudest advocates for white pine restoration in the state. For over a hundred years his family’s company has been logging white pine, and he has seen how it does not return. So he has made it his personal mission to restore white pine on a massive scale: to ensure that

others will be able to experience the awe and grandeur a stand of old growth pines inspires in him.

Over the last twenty-five years Rajala has planted nearly four million seedlings on company land. Out of the 200,000 seedlings planted per acre, only five or six hundred survive into adulthood; of those, Rajala hopes to have fifty giants—pines over a hundred years old—trees he will never see, but in which he believes heartily.

Rajala’s mission has cost him large amounts of time and money to address the challenges. First, the land is cleared and the soil prepared for seedlings. Fire would naturally serve this function, but logging, too, can make the necessary space. Then, because natural seed sources are few and far between, Rajala and his team of silviculturalists plant nursery raised seedlings. They deter invasive pests from the start by balancing the canopy thickness: enough to keep the seedlings cool and dry (conditions not conducive to blister rust or the white pine tip weevil), but not so much the sun can’t get in.

Once the trees are in the ground, they monitor them to ensure they are not smothered by competing deciduous trees. Each spring they cap the buds with small pieces of paper to prevent deer browse. After about five years, when the trees are over six feet tall (out of deer’s reach), the trees have made it past the major obstacles, but the process still isn’t done. The pines must be continuously trimmed and thinned as they take up more space in the forest, and young trees must be brought up to replace the old ones as they die or are cut. As Rajala learned the hard way—having lost about a million seedlings in the early years—growing white pine does not happen by putting a seed in the ground, but rather requires assiduous attention throughout generations.

The threat of blister rust

Faced with insufficient seeds, thick undergrowth, and hungry deer, it is no wonder foresters said it was impossible to raise white pine, and to top it all off, they reasoned—blister rust, an invasive fungus, made the whole endeavor a fool’s errand. Blister rust infects a pine’s needles during cool, wet days and can kill a tree by spreading to the branches, then the trunk, though older pines can survive because they only lose their lower branches. Ironically, this disease has actually helped white pine restoration by being a focal point for research that raised the white pine issue and developed regeneration techniques.

In the 1950s, long before white pine was political, Cliff and Isabelle Ahlgren began a comprehensive collection of plant materials at the Wilderness Research Centre—a project of the Hubachek family, whose devotion to wilderness led them to found the research station and later donate it to the University of Minnesota. The Ahlgrens spent over thirty years at the Basswood Lake station in what is now the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness and then, after the passage of the 1978 BWCA Wilderness Act, on Fall Lake, near Ely, Minnesota.

Cliff’s efforts to identify blister rust resistant white pine trees set thebaseline for white pine research, which is continued today by University researchers at the same Fall Lake station. U.S. Forest Service researchers are also investigating white pine genetics and blister rust resistance. In the rush of funding after the legislative changes of the 90s, blister rust became a hot obstacle for research to surmount and the results have been helpful—developing techniques and new plantations—but as of yet there have been no revolutionary changes in white pine planting. Rajala takes this pragmatic perspective: blister rust has arrived to stay, but it will only kill about 25% of white pines that are planted. So plant more trees.

A change for the better

Rajala has clearly carried out this declaration—a very practical approach to a complicated problem. He is, in essence, a doer, and so he attacks the lack of white pine with vigorous action. In his turn, Lynn Rogers worked hard to preserve white pine at the legislative level, and Lee Frelich is an expert in forest ecology, consulted by many public agencies and planning committees. Individuals from gardeners to governors have made it their mission to see that there will be more white pine in Minnesota’s future.

Thanks to the legislative changes of the late 90s and the swell of public support, white pine cutting has slowed nearly to a halt. Preserving and growing new white pine is now a primary goal. There are active research stations, nurseries, and plantations. In raw numbers, white pine has gained ten thousand acres in the last ten years. Yet, there are still more strides to be made.

For their part, the DNR has the resources to control excessive deer populations. Through hunting permits and emergency feeding programs, they have long worked to augment deer herds. In a series of public forums all over Minnesota in the last year, the DNR heard a resounding call for fewer deer, by as much as half in some places. Although bud capping works, it is expensive, time intensive, and needs to be done right so it doesn’t damage the seedlings; still there are the trees that don’t receive such attention. Reducing the deer population statewide solves the problem at its source.

Other advances in forest management can be seen in the BWCAW. Tracts are being intentionally burnt to reduce the threat of uncontrolled blazes, fueled by the massive acres of forest that blew down in the 1999 wind storm. Already 37,000 acres have been burned, showing that we can effectively mimic the natural fires that stimulate forest development and are especially important at clearing the space for white pine seedlings.

The Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy (MCEA) recommends changing how the forests are harvested, as well. Currently, logging dissects the forest into scattered blocks and cuts the older, more profitable trees. This perpetuates forest fragmentation and further disturbs the natural spatial patterns of the forest and its ability to sustain the native forest plants and wildlife. Cutting older trees removes seed sources and deer more easily devour these smaller stands when they are replanted or seeded to native pines. The MCEA would rather see forest management that includes younger stands and recreates the larger forest patches that are closer to Minnesota’s original conditions, and hence better able to withstand deer browse and regenerate naturally.

Deer, fire, and harvesting techniques are just some of the ways that white pine management can continue to evolve. The DNR, the Forest Service, and the Minnesota Forest Resource Council’s landscape strategy work groups have set goals for what Minnesota will look like in one hundred years, but now the public agencies must see that they come to pass.

Looking ahead

All of these efforts, from the Ahlgrens’ research to the MCEA’s policy monitoring, have given white pine a chance to thrive in the future, but their success will not be apparent for another hundred years. This kind of timeline—stretching beyond one governor’s term or even one person’s lifetime—is difficult to sustain. Rajala’s successful forests show that “walk away forestry does not work,” but we can make a difference, if only we are diligent. As a private agent, he has been able to manage his lands with the necessary continuity. Conversely, federal and state lands are under ever shifting management. From presidents to forest supervisors to park visitors, the public stewards of the land change all the time, and with them, what are the most important issues of the day.

The white pine benefited from the rush of public support and scientific research of the last two decades, but all of these efforts will be for naught if they are forgotten when the next political hot topic takes center stage. A lot can happen in one hundred years, insists Matt Norton, a forestry advocate with the MCEA. White pine can grow into giants and forests can fill acres that were once barren. For him, the necessary commitment is clear: “If we want to work some kind of apology on the landscape for the excesses of the past we have to recognize that will take analysis, planning, intention, and resources.” For Norton, and all those who have worked tirelessly to champion Minnesota’s forests, the key is to believe this, and to invest in it. In this way, restoring white pine is a tangible opportunity to fulfill our

obligation to the land, to use our knowledge and experience to ensure that the forest can thrive

in the future.

By Laura Puckett, Wilderness News Contributor

This article appeared in Wilderness News Summer 2006