By David Woodward, Archaeologist, Superior National Forest, USDA

Interdisciplinary Archaeological Studies, Department of Anthropology, University of Minnesota

Northeastern Minnesota today is a cultural landscape, a rich land that has been owned, mined, plowed, and clear-cut of timber. It is a land that has been continually molded by history and constantly reminds us in a clear voice of its past. Place names remind us of both its Native American heritage and the more recent European expansion, pictographs stand witness to the ancient inhabitants of this region.

Ten thousand years ago this was also a cultural landscape, but the voice of this era is a whisper. Before there were towns and easily accessed resort areas this was a region cherished and contested by generations of hunter-gatherers whose impact on the land leaves barely a trace today. Archaeologists attempt to visit this landscape and hear the whisper of this distant past. The individual voices are irrevocably lost, but the aggregate voice can still be heard.

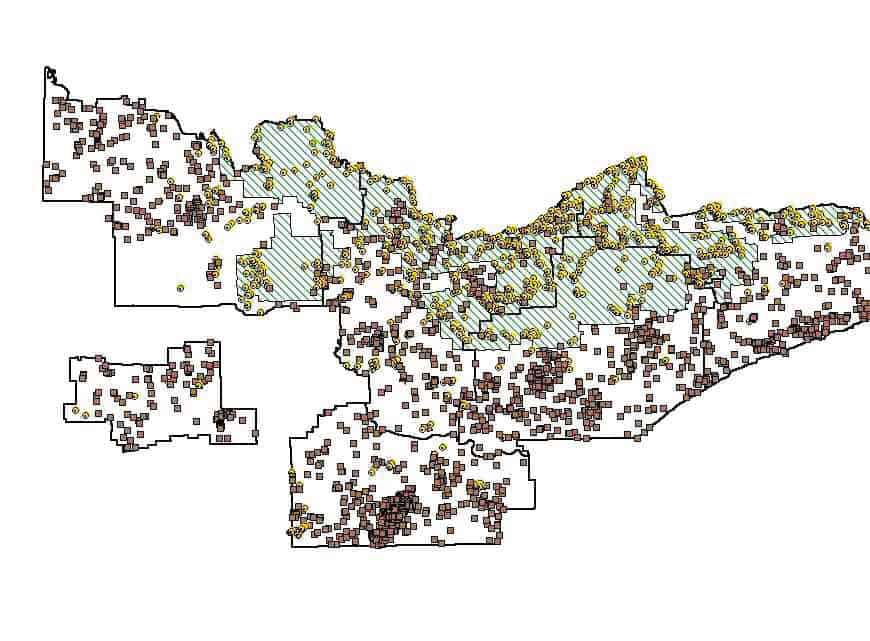

It is with this in mind that archaeologists working in the Superior National Forest’s Heritage Program survey and evaluate historic and prehistoric sites in an attempt to preserve the scant evidence of 10,000 years of human occupation both in and outside the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. In the 25 or so years of the Heritage Program’s existence 3,560 historic and prehistoric sites have been located with about 100 additional new sites found each year. The Heritage Program was developed by the USDA Forest Service in response to federal legislation (The National Historic Preservation Act among others) which mandated that federal land management agencies take into consideration the effects of their projects (such as campsite rehabilitation, prescribed burns, and road maintenance and construction) on historic and prehistoric sites. A major focus of the Heritage Program is stewardship, through public education and involvement. It is hoped that we all can work to protect our fragile heritage. Currently, the Superior National Forest employs 5 to 8 archaeologists and archaeological technicians conducting pre-project site location surveys, site monitoring and the formal evaluation of previously recorded sites. Formal evaluation entails detailed excavation of a small portion of an archaeological site to determine if that site meets the criteria to be included on the National Register of Historic Places, which then affords it the highest level of protection and preservation.

Aerial view; confluence of Cross River and Gunflint Lake. Photo courtesy Forest Service Heritage Program.

It is through this process of site survey and evaluation that we get a glimpse of the prehistoric past. One example of this process is the recently excavated site, the Gordon’s Site. The site is located at the confluence of the Cross River and Gunflint Lake. Gordon’s Site was found in 1989 during a routine survey of the banks of the Cross River and named after Gordon Peters, the founder of the Superior National Forest’s Heritage Program. During the initial survey a small amount of stone debris was found just below the surface on the north bank of the Cross River. The site was monitored to assess the damage caused by the blowdown caused by the 1999 Fourth of July wind storm. At this time bifacial knives and scrapers were found in root throws and on the surface. The artifacts were found over an area of about 400 square meters, a much bigger area than previously thought. No pottery was found at this time and to date only two small fragments of pottery have been found near the surface. In the historic chronology of the region, ceramics appear sometime around 300 BC; the scarcity of pottery is good evidence that the occupation of this site predates this period. Because of its possible age and location at the confluence of two water bodies this site had potential to provide some important information about the ancient pre-ceramic people that inhabited the area.

The Forest Service Heritage Program conducted test excavations on the site during the summer of 1999 and in 2000 returned to the site with volunteers from the Passport in Time Program to continue investigating the site. The Passport in Time is a national organization that provides volunteer opportunities to people interested in history and prehistory. The site was also open to the public for tours and over 1,000 people visited. During these excavations a large amount of stone debris was recovered along with burnt bone from cooking, copper tools, stone scrapers which act as an all purpose tool, stone awls for bone and hide working, and projectile points from the early to middle Archaic period which date from 7,000 to 3,000 BC. The burnt bone has been analyzed and is from beaver, muskrat, and possibly caribou. In addition, the lower reaches of the excavation provided tantalizing evidence of an earlier deeply buried Paleo-Indian occupation on the sand terraces which rise up from the Cross Bay River. These sand terraces could be ancient beach benches from the Glacial Lake that formed as the large ice sheets began melting. At the time no formal artifact recovered could be placed in the Paleo-Indian time frame dating to the earliest period of human occupation of North America (circa 10,000 – 7,000 BC).

During the summer of 2004 Forest Service Archaeologists returned to the Gordon’s Site. This time a more focused approach to the site was warranted. The excavation was limited to the sand beach terraces in an attempt to get better data on the possible Paleo-Indian occupations of the site. Again volunteers from the Passport in Time Program took part in the excavation along with Anthropology students from the University of Minnesota Duluth’s Field School. The site was also open to the public. The excavation recovered biface stone knives, scrapers, awls, copper tools, and projectile points along with debris from stone tool manufacturing and a lot of burnt bone from cooking. One of the projectile points can be placed with reasonable certainty in the Late Paleo-Indian Period, which is the evidence that can put this site’s occupation at that earliest period.

The thousands of artifacts recovered so far are testimony to the day to day lives of a people now lost to time. We can only construct a very limited picture of what life was like thousands of years ago. We do know that these people were migratory foragers that moved with the seasons and harvested different resources depending upon the season. The environment changed drastically in the 10,000 years before European contact, from cool tundra during the Paleo-Indian period, to a period marked by a warmer, drier, climate with a mixed deciduous hardwood forest during the Archaic and then to the cooler wetter period that begins about 500 BC and continues to the present day. The people inhabiting the region adapted to the changing climate and redirected their subsistence efforts, from large game hunting during the Paleo-Indian to a more diversified foraging during the Archaic and then finally to

a slightly more sedentary lifestyle with a reliance on wild rice and larger seasonal villages. At least part of this story is played out at the Gordon’s Site from the Late Paleo-Indian to the Archaic.

At the Gordon’s Site the major Archaic habitation seems to be along the Cross River and a early to middle Archaic projectile point was recovered while the Late Paleo-Indian habitation seems to be at higher elevations away form the current shoreline of the Cross River. This could reflect the change in environment and subsistence over a period of environmental change.

There are many questions about the past that will never be answered. What did it mean, for example, to draw the figure of a moose with red pigment on a cliff face, or to bury elders in a collective burial mound some 2000 years ago?

This work is a case study in reconstructing the lives of hunter-gatherers from the distant past, but it is also a cautionary tale about how limited our abilities are, how soft the whisper really is.

Archaeologists from the Superior National Forest will return during the summer of 2005 to continue the excavation. The site will be open for viewing from 9:00AM to 3:00PM from June 28th through July 14th including weekends. Again volunteers from the Passport in Time Program will be working with Forest Service Archaeologists. The public is encouraged to visit and learn about the area’s rich history. People interested in volunteering to excavate the site should contact the Passport in Time Clearing House at 1 (800) 281-9176 or can be found on line at www.passportintime.com.

This article appeared in Wilderness News Spring 2005