By Rob Kesselring

Archaeologists are painting a picture of Quetico-Superior’s first people and what the land looked like 12,000 years ago.

Crouched behind a granite boulder we wait. A damp northwest wind off Lake Agassiz raises goose bumps on our naked thighs where our caribou leggings end and what our summer tunics do not completely cover. But we remain poised, ready, our fingers gripping the atlatl and the shaft of its spear. For generations herds of caribou have funneled through the gap in the ridge that we now face. This week we need to kill many animals just to outfit our family with winter clothing and shelter. We are confident hunters. The long stone point on our spear was carefully knapped to a razor’s edge from Knife Lake siltstone. You call us Paleo-Indians and we are the first humans to explore the grandeur of the Quetico-Superior wilderness, and we arrived earlier than you might think.

It has been believed that the Quetico-Superior wilderness after being cloaked, scraped clean, and flooded by the last glacial advance was, for a long span of time, too inhospitable for human habitation, but recent research indicates otherwise. It now appears that people followed the retreating ice like ticks on a moose.

In the modern world, we clench our jaws if we punch the wrong icon on our smart phones and need to spend an instant to correct our mistake. That kind of thinking makes it hard to comprehend the passage of time during the early human occupation of the Quetico-Superior. The ice sheet that covered the area was over a mile thick. It did not melt away in a year or even a century. The ice sheet retreated over the span of a couple thousand years. So slowly, that in a person’s lifetime, it would be hard to notice the ice was retreating at all. The biome behind the retreating ice was incubated by a relatively low latitude sun, which created unique and especially nutritious tundra vegetation. This food source created a desirable habitat for a multitude of barren-land caribou, musk ox and likely the now extinct wooly mammoth. With a smorgasbord like that, saber tooth tigers, 300-pound wolves and hungry people were not far behind.

As slowly as life was moving 13,000 years ago, it was a barn dance compared to the speed of geologic processes three billion years earlier. That is when a volcanic mountain range in Canada had worn itself down to dust and settled as silt where Knife Lake is today. The silt became shale and from the heat of nearby granitic intrusions was forged (or metamorphosed) into Knife Lake Siltstone, setting the stage for the first human explorers. Skilled Paleo-Indians could work (or knap) this extraordinary rock into durable knives and spear points. Without the technology of even the bow and arrow, Paleo-Indians esteemed a rugged and sharp spear. No family man wants his or her spear to bounce off a wooly mammoth or a pouncing saber tooth tiger.

Knife Lake straddles the border between Ontario and Minnesota, with Quetico Provincial Park to the north, and the BWCAW on the American side (N48 W091, Elev. 1401 ft.). Its higher elevation than the surrounding landscape kept it above the water level of the massive proglacial lakes of Agassiz to the west and Duluth to the east and gave Paleo-Indians access to the siltstone even as western portions of the Quetico-Superior were still submerged.

Although earlier anthropologists surveyed the area and noticed a preponderance of flakes (sharp-edged stone fragments created by humans striking or prying in the process of tool making), it was Canadian archaeologist William Fox in 1977 who actually discovered the first siltstone quarries. But “discovered” is the wrong word. The French fur traders’ name for Knife Lake was Lac des Couteaux, or Lake of Knives, pushing “discovery” back a couple centuries. Lac la Croix Ojibwa elders have translated the lake’s Ojibwa name Mookomaan Zaaga’igan to mean “Lake where rock used to make knives is found”. In fact, the knowledge of the Knife Lake siltstone may have been uninterrupted for over 13,000 years. It might have been an extraordinary example that sustainable mining is actually possible. But the archaeological record does not seem to support this. Artifacts of later Archaic peoples and more modern woodland cultures are not found atop the Paleo-Indian artifacts near the quarry sites. This indicates that as technology changed there was a preference for different raw materials and that the quarries had been abandoned.

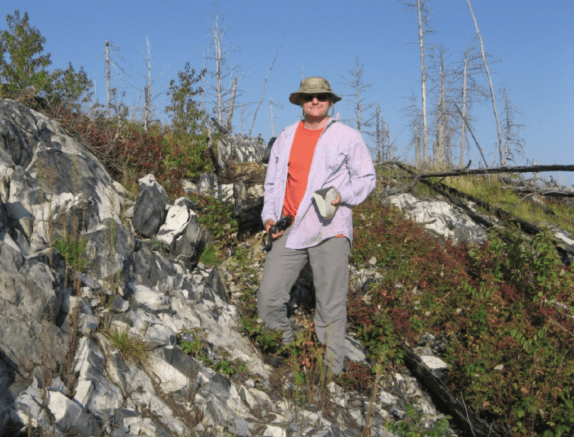

Jon Nelson did the first substantial archaeological research of the quarries about two decades ago. His excellent book, Quetico Near to Nature’s Heart, describes his amazing discoveries. Nelson worked on Knife Lake’s north shore. Until recently, it was believed that the only quarries were on the Canadian side of the lake. But the old cliché, when one door closes a window opens, happened. The slamming door was the devastating 1999 blow down. This event wrenched the hearts of many lovers of the Quetico-Superior wilderness. However, after the Forest Service completed a series of prescribed burns to reduce the windfall fire load, a window was opened. Stripped of the cloak of vegetation, large-scale Paleo-Indian quarry sites were revealed on the American side of the lake.

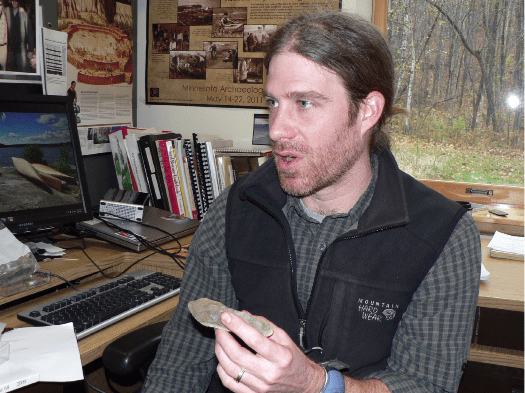

After this discovery Mark Muñiz, associate professor of anthropology at St. Cloud State University, led several research trips to the area. The research sites are within the BWCAW and Superior National Forest Archaeologist, Lee Johnson, has accompanied and assisted Muñiz with technical expertise and logistical support. Muñiz’s groups travel by canoe, portaged their gear and adhered to no trace camping practices. Muñiz’s latest findings have garnered headlines and may someday turn conventional thinking upside down. New revelations, a bit of controversy and with wilderness and canoes as the stage? The excitement is palpable. You can almost hear the theme song of Raiders of the Lost Ark playing in the background.

It has long been believed that the earliest humans to live in Minnesota did so in the south. That theory is now being tested. Muñiz has collected soils found associated with the stone tools. Using a relatively new diagnostic test, optically stimulated luminescence (OSL), it is possible to determine the date soil samples were last exposed to daylight. If OSL dated soil is found in a layer above the artifacts, it stands to reason that the tools are at least that old. When one soil sample was OSL dated 16,400 years ago (plus or minus 2,000 years), eyebrows of archaeologists around the world went up. Johnson cautions that this is a preliminary, inconclusive finding. Ideally, similar radiocarbon dates of charcoal found at the site and the discovery of a fluted point indicative of the earlier Paleo-Indian period are needed to corroborate these astonishing OSL findings. Muñiz plans to return to Knife Lake in search of these clues and to do more OSL testing—a process that involves collecting samples in the dark of night and paddling them out of the wilderness in lightproof containers!

Excitement is contagious. Readers may be tempted to do a little amateur archeology. Please don’t. What has enabled scientists such as Nelson, Muñiz and Johnson to learn so much from these sites is their undisturbed nature. Archaeological digs are like a layer cake and often the location and position of artifacts is as important as the artifact itself. In the Quetico-Superior wilderness, this is particularly true because soil layers are extremely thin and fragile. This “no-touch” mandate goes beyond the quarries of Knife Lake. Johnson estimates that 60% of the campsites in the BWCAW are also archaeological sites. It should not be surprising. Canoeists last August or five thousand years ago are often looking for the same thing when it comes time to camp. If you stumble upon artifacts or evidence of prehistoric people, do not dig around or even handle the artifact. Instead, take a GPS reading or mark a map and e-mail the data to Johnson (leejohnson@fs.fed.us). In that way, you can be an important part of the science.

Undoubtedly, some key puzzle pieces critical to visualizing the mysterious human prehistory of the Quetico-Superior wilderness are already collecting dust on some canoeist’s family room shelf in St. Louis or Chicago. Don’t be part of the looting. Maybe you already have a stone artifact that you found on a canoe journey in the Quetico-Superior. Do the right thing now and contact Lee Johnson with the details of where and what you found.

These ancient artifacts are remnants of the first humans to inhabit the region and are an integral part of the wild mosaic that makes the Quetico-Superior special. The First Nation people of Lac La Croix most closely share their blood with these ancient people. Nelson reports that the elders can feel in their hearts how the stone tools resonate with the spirit of the land and create a harmony between this world and another dimension. Like the submerged keel on a sailboat, these ancient artifacts may not be obvious, but play a crucial role in keeping the sailboat or our evolving culture afloat. The energy of that ancient hunter patiently waiting for caribou still stirs in our souls. Pragmatically, modern canoeists have learned that if you honor the sanctity of these ancient implements you will face fewer headwinds, find more dry firewood and experience sunnier days.

This article originally appeared in Wilderness News Fall Winter 2013 >