Ten Years After the Ham Lake Fire: A Forest Regenerates

By Alissa Johnson, July 3, 2017

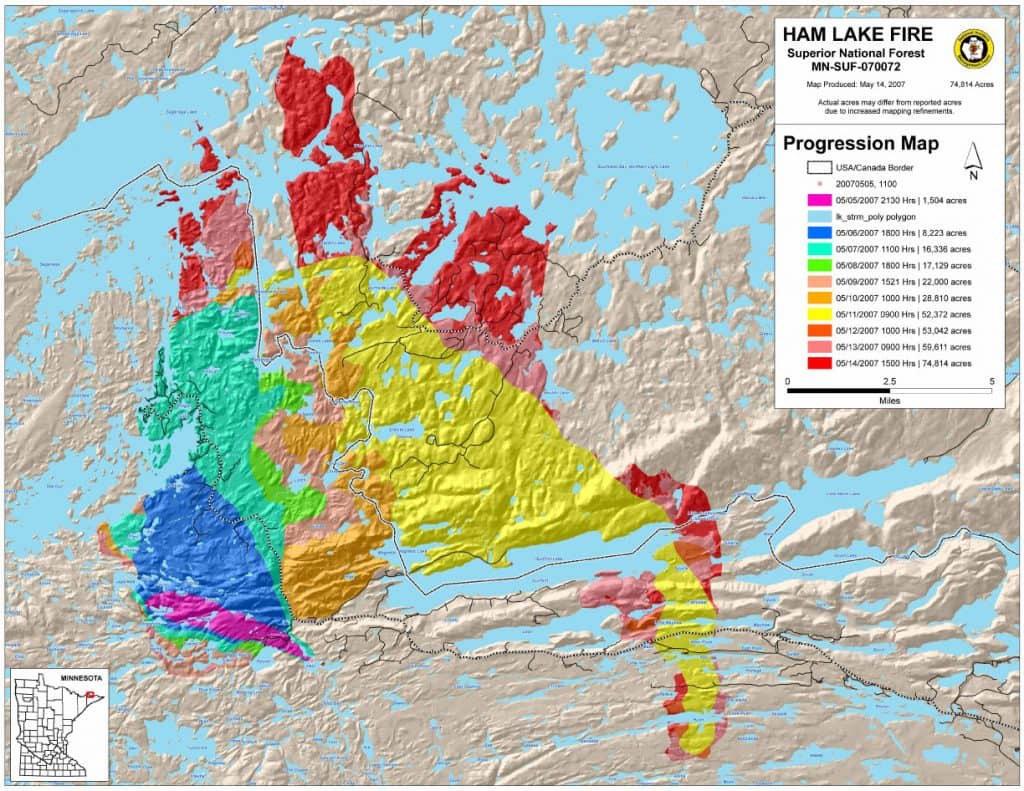

Ten years ago last May, an out of control campfire off the Gunflint Trail grew into a wildfire that burned 75,851 acres, a little less than half in Minnesota and the rest in Canada. On the U.S. side of the border, portions of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW) and Superior National Forest burned, and on private lands, more than 140 structures were lost. The Gunflint Trail was evacuated, and images of the devastation were arresting: satellite imagery of smoke drifting across canoe country, and acres of charred, black trees. But what about today? Ten years later, the forest is at a turning point. While it is a far cry from what it once was, it is beginning to look and feel like a forest.

A Stark Contrast

The difference between what the forest looks like now and what it looked like after the fire is striking. Michael Valentini, a property owner on the Gunflint Trail, remembers what it was like to return to his property after the fire. While two and a half acres had been spared thanks to a sprinkler system, he said that “at the road to the property, everything was burned and black.”

At the time, it was probably hard to imagine the forest regenerating and green returning to the landscape. And yet it has. Nancy Seaton, who owns Hungry Jack Outfitters with her husband, David, reflected on how much burned areas along the Gunflint Trail have transformed.

“Burned trunks remain,” she said. “But all the branches from the burned trees have fallen and we have green trees that are 20 feet tall… It’s so green that it has a look of promise as opposed to devastation.” While neither Valentini or Seaton would go so far as to say that you can’t tell a fire happened, they both agreed the forest is coming back.

“If you come in summertime, you most likely won’t notice much,” Valentini said. “What you will see is that so much understory has regrown over the years, and a lot of poplar and jack pine and balsams have sprouted up.”

The Surviving Forest

Prior to the Ham Lake Fire, part of the forest was damaged during the blowdown of 1999, when millions of trees fell during a massive storm. According to Patricia Johnson, fire management officer with the Superior National Forest, the forest composition was a jack pine landscape ecosystem. “It would primarily be jack pine with red pine and spruce being secondary species. There would also be a mix of other boreal species depending on soil types including birch, aspen, cedar, white pine, balsam fir,” she explained.

According to Dr. Lee Frelich, director and research associate at the University of Minnesota Center for Forest Ecology, the timing of the fire played a role in how that landscape burned and then regenerated. Spring fires, as opposed to summer, affect the landscape differently because the organic matter in the soil is still wet from snow melt. The fire doesn’t burn as deep into the duff and the forest doesn’t burn consistently as a result.

“The burning pattern on the forest floor is very patchy,” Frelich said. So in some areas of the Ham Lake Fire, standing pines remain. Where the forest did burn, more aspen have regenerated than birch. “That has to do with the timing of the seeds and how deep the fire burns into the duff.”

Frelich’s PhD student, Eli Anoszko, compared the regeneration of the Ham Lake Fire to the 2006 Cavity Lake Fire, which occurred in late July. The latter has more birch, whereas there are more aspen in the area of the Ham Lake Fire. There are also fewer conifers coming back than might be expected. Frelich attributes this to a warming climate, based on research he and his PhD students have conducted.

Patty Johnson believes the overriding factor affecting forest regeneration is the blowdown, which took out seed sources. “Considering the blowdown, [the forest] is regenerating as we would expect it to. If the blowdown hadn’t occurred, we would have expected more conifer,” she said.

A Turning Point

Where aspen have grown, Frelich says the forest is starting to form a canopy. The understory is thick, however—what he called “dog hair thick.” A person would need to push saplings aside to walk through it. There are also fallen logs and standing snags that make good habitat for species like the black-backed woodpecker and insects. And the forest makes good habitat for moose.

“Once aspen are five or six feet tall and dense and brushy, moose start going in there. Young birch and aspen are among their favorite foods,” Frelich said, though pointed out that the density of the trees might make it hard to spot them. This young forest is, however, in a point of transition. “Ten years is a turning point when the forest is going from post-fire regeneration back to a forest.”

In the first years after a fire, a lack of trees allowed more sunlight to reach the forest floor and leaves more nutrients for plants. As a result, blueberries have been abundant. Large leaf aster, which most folks know as “lumberjack leaves,” have grown large and actually flowered. Clintonia, or the blue bead lily sometimes mistaken for blueberries, have also been larger than normal. They likely still are, but that will change in coming years. As the trees continue to grow, the canopy will close in, Frelich said, and the forest floor will become darker. Over the next several years, there will be fewer blueberries. The large leaf aster and blue bead lily will return to normal size. Aspen trees will begin to lose their lower branches so the forest floor becomes more open.

A Natural Cycle

As the forest regenerates, it’s a chance to see the role of fire in the boreal forest up close. As Johnson said, the region is a boreal forest, and while the Ham Lake Fire was caused by human activity, the landscape depends on fire.

“It burns regularly on the landscape,” she said. Depending on the vegetation, it could be every 25 years or every 500. That creates a mosaic across the landscape, where the trees and vegetation indicate how recently a fire burned.

Some, including Frelich, can read that mosaic and give you a history of the fire. Cary Griffith is the author of the forthcoming book Gunflint Burning. He shared a story about Frelich taking two travel companions to the top of Three Mile Island on Seagull Lake. “He looks out over the forest and is so astute and knowledgeable about forest fires [that he] could tick off the 500 year history of all the fires that happened just by pointing to different parts of the forest canopy.”

So perhaps another way of looking at the Ham Lake Fire? A visit to the Gunflint Trail now is an opportunity to see a forest in action, and how fire plays out across the landscape.

Even as the forest regenerates, there is no denying that humans were widely affected by the fire. Our friends at WTIP, North Shore Community Radio, have put together a broadcast on the impact of the fire on the people of the Gunflint Trail and their livelihoods.