In northern MN, broad swaths of forest are turning brown. The Spruce budworm, native to Minnesota, has spiked in numbers as state and federal agencies, along with conservationists, are working to mitigate the issue. Repeated and sustained outbreaks, seen in dead or dying balsam fir and white spruce are a signal of poor forest health. While budworm cycles are natural, studies show an increase in outbreaks, likely linked to human impacts from early 20th-century logging and fire suppression. As a result, agencies have implemented management plans and regeneration efforts to diversify the forest.

Worst outbreak since 1961

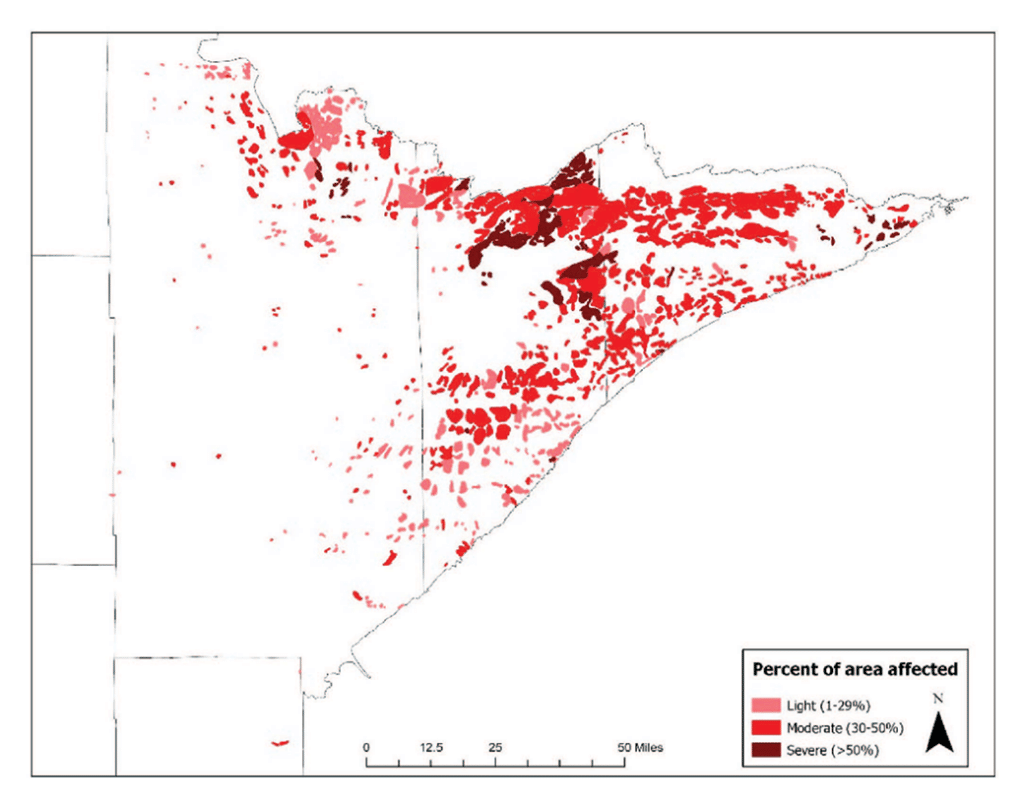

Since the early 1960s, the budworm has increasingly damaged large forested areas in Minnesota, with the worst outbreak occurring last summer. This includes the Superior National Forest (SNF, the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW), along with other public and private land. In the past four years, the infestation has significantly increased, affecting 2,000 square miles (1,330,000 acres).

This growth has raised concerns about a potential increase in wildfires and forest management challenges. Approximately 519,000 acres are impacted annually, equivalent to the combined area of Lower and Upper Red Lake, Leech Lake, and Mille Lacs Lake. Last year, the infestation rose by 7% from the previous year. State researchers have noted that the outbreaks are cyclical, lasting 6-10 years, with the budworm returning every 30-40 years. However, due to numerous reasons, the forest has struggled to keep up with the increase.

Human impact behind surge

Human activities have mainly caused the rise in budworm impact. Starting with the logging boom in the 1800s, lumberjacks felled trees, and quick-growing balsam fir repopulated the area, forming dense stands. As the woods matured, the spruce budworm moved in. Though budworm prefers balsam and spruce, it will feed on other trees when its numbers saturate the area.

Consequently, this attracted deer to the young forest. However, deer don’t eat balsam fir and prefer species like white pine, white cedar, birch, and aspen. As white pine, once a dominant species, struggled to regenerate due to factors like browsing, the forest became less diverse.

Moreover, fire suppression and management actions in recent decades have made the forest more susceptible to budworm outbreaks. For many decades, people viewed wildfires as destructive forces that threatened human safety and timber resources rather than adopting a more balanced approach.

Sometime between 2013 and 2016, the cycle of outbreak started beginning to the east of the SNF slowly moving northeast towards Lake Superior.

The budworm lays eggs on the tips of needles in mid-summer. Later, the larvae overwinter in a silken tent on pine branches. The following summer, they emerge as moths and continue the cycle.

Collaborative approach to sustainability

State and federal agencies in partnership with conservationists are using a multipronged approach to tackle the issue.

The USFS management continues through controlled burns, and in certain areas like the BWCAW, lightning-caused fires will be allowed to burn under specific conditions.

In 2024, a $3.5 million grant went to the Nature Conservancy, which has been clearing and planting to create a more diverse and healthier landscape. The organization established 2.3 million trees last year and plans to focus on key areas of damage. As trees mature, the conservancy will revisit the plantings every couple of years to check on the new trees.

State agencies continue to work with coalitions of landowners and conservationists to apply forest management practices. These include assessing properties, thinning dense stands, and planting fire-resistant species. Dead or dying trees will continue to be harvested to reduce fuel loads created by the caterpillar.

Kyle Stover, District Silviculturist with the Tofte Ranger District, said in a webinar update, “We prioritize clear-cutting, especially now with spruce plantations that are dense or balsam fir stands that lack species diversity.” He added, “We focus on those stand conditions while the trees are still marketable.” Stover also explained that nonmarketable wood is cut and burned, particularly when the budworm has devastated the stand. The revenue from the timber sale then goes back into trusts that fund forest regeneration.

Aerial surveys have been used to study the forest since the 1950’s. This has served as a valuable tool for tracking and managing forest health and threats like the budworm. “By tracking changes and trends in tree health, the DNR provides information that landowners and forest managers can use to make our forests healthier and more resilient,” said Brian Schwingle, DNR Forest Health Program Coordinator.

Those who are interested can view the USFS webinar on Spruce Budworm Management in the Superior National Forest.

More info:

- In Minnesota’s Arrowhead, balsam firs ravaged by an especially bad spruce budworm outbreak ramp up fire fears – MinnPost

- Spruce Budworm in Minnesota’s Forests 2024 Update – Cook County Higher Education

- Tofte Landscape Project – USFS – Superior National Forest

- Blue Cascade Project – Spruce Budworm Response and Restoration – USFS – Superior National Forest

Wilderness guide and outdoorswoman Pam Wright has been exploring wild places since her youth. Remaining curious, she has navigated remote lakes in Canada by canoe, backpacked some of the highest mountains in the Sierra Nevada, and completed a thru-hike of the Superior Hiking Trail. Her professional roles include working as a wilderness guide in northern Minnesota and providing online education for outdoor enthusiasts.