Researcher warns of increasing impacts and urges end of axe and saw culture.

A canoeist paddling along the shore of a Boundary Waters lake will see miles of unbroken forest. Trees grow and fall and rot, water washes against rock and soil, all unaffected by humans. Then, arriving at a campsite, a much different landscape often greets the paddler, abundant with human impacts.

With stewardship by visitors and proactive management by the Forest Service, the experience at campsites could be nearly as wild as the surrounding shoreline, says researcher and Leave No Trace advocate Jeff Marion.

Marion says wilderness visitors should leave the axe at home in the future. After completing a study of campsite impacts, he believes ongoing degradation of trees at wilderness campsites means it is time to restrict the use of woods tools.

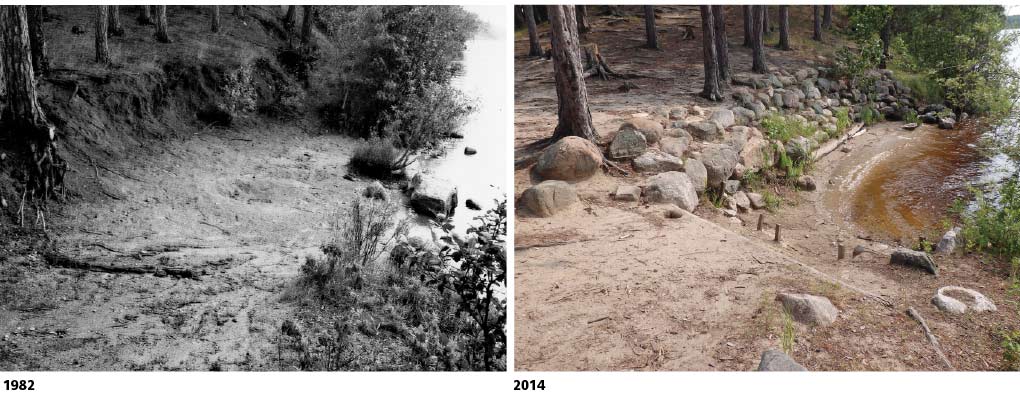

Marion is a professor at Virginia Tech University, a research biologist for the U.S. Geological Survey, and the author of a 2014 guidebook titled Leave No Trace in the Outdoors. He was also a founding board member of the Leave No Trace national organization. Marion first studied human impacts in canoe country in 1982, and returned this summer to examine conditions again and compare them to his findings from 32 years ago.

To conduct the study, Marion and three assistants surveyed 81 of the 96 campsites he examined in 1982, and made 94 measurements at each one. They collected information about campsite size, vegetation cover, tree damage and root exposure, and soil conditions. The team is still compiling their data, but can see some trends.

While some issues appear to have improved, marking a more natural wilderness character, Marion says he was disappointed to see continued felling and damage to trees, which he called “avoidable impacts.” Stumps and scarred trees are apparent at many campsites, even though wilderness visitors are instructed to gather only dead and down wood, smaller than wrist-sized. There were two-thirds as many trees and half as many tree seedlings at the campsites in 2014 as in 1982.

“I’m not sure why the Leave No Trace messaging related to those impacts seems to be ineffective. I will be recommending to the Forest Service that they prohibit woods tools. When education is ineffective it’s time for regulation and my data would fully support such an action,” Marion said.

The Forest Service provided ‘seed money’ and collaborated on Marion’s study, and says it is reviewing his findings. But, Superior National Forest wilderness specialist Ann Schwaller said “banning wood tools doesn’t have to be the only solution, if more people were educated about low impact camping.”

“We need all kinds of advocacy groups to speak and write about wilderness Leave No Trace and tread lightly practices to… anyone that goes into wilderness, and not just about this issue, but also about many other resource issues as well,” Schwaller said. “Help be part of the solution. Try to reach as many people as possible about responsible camping.”

That call for individual action is not simply a way to avoid new regulations, but recognition of the limited resources available to the Forest Service. Schwaller says the time that rangers spend shoring up erosion, cleaning up campsites, and otherwise responding to poor visitor behavior, could be spent on critical issues like removing invasive species and tackling a backlog of restoration projects. She also said that restricting what tools Boundary Waters visitors are allowed to use could violate other wilderness management goals.

“Prohibiting tools is one more regulation that affects wilderness character—the primitive and unconfined recreation quality,” Schwaller said. “However, we agree that misusing woods tools damages campsites, hurting the wilderness character quality of naturalness.”

Tree loss caused by the use, abuse, and misuse of wood tools could be responsible for another negative trend that the 2014 study revealed: campsites are getting bigger. Marion theorizes that, as sites are getting sunnier because of tree loss, campers are carving new tent pads out of the forest to find shade. The number of these “satellites” more than doubled between 1982 and 2014, leading the growth of overall campsite size. It’s also possible that a new phenomenon has appeared in camper behavior: people don’t just want a good distance between themselves and the next campsite, they want privacy even from their companions, and don’t want to pitch their tents next to each other.

There are ways to subtly remedy this problem. On the Appalachian Trail, more than 600 campsites have been constructed on the sides of hills. “Small but ideal” tent sites are cut into gently sloping terrain to prevent campsite sprawl.

“Visitors then concentrate all their camping activity on these small campsites, which don’t enlarge over time due to natural topographic constraints.” Marion said. The practice has achieved “substantial success” in reducing camping impacts, including size, vegetation loss, soil exposure, and soil loss.

The intense use of campsites in the Boundary Waters also means they are literally washing away, as soil, disturbed by campers and loosened by tree loss, erodes. Marion’s research found that each site had lost approximately 26.5 cubic yards of soil in the past three decades—almost 6,000 dump truck loads of dirt for campsites across the Boundary Waters. Four out of ten trees showed evidence of moderate to severe damage and root exposure. This process contributes to the cycle of expanding campsites.

“The slow but inexorable process of soil loss on campsites will cause tent spots in the core campsite area to become less attractive due to roots, rocks, or uneven soil,” Marion said.

The Forest Service can’t very well move all 2,200 sites in the BWCAW to hillside locations, but other options exist to contain campsites. Flat tent pads could be constructed and maintained in the core of sites, providing desirable locations and discouraging campers from making their own pads elsewhere. From a Leave No Trace perspective, intensive management in a smaller area is preferable to a chaotically growing site, shaped by human desires rather than wilderness protection considerations. The Forest Service had been trying to replace soil and keep tent pads usable, but Marion says budget cuts have “nearly eliminated that capability” in the last decade.

Marion sees his findings and the recommended responses as fundamental understanding for sustainably managing the Boundary Waters. While prohibiting axes and saws might fly in the face of cherished traditions, it is better than the alternative: banning campfires. That approach has been implemented at many National Parks, primarily as a means to reduce damage to standing trees.

“The slow but inexorable process of soil loss on campsites will cause tent spots in the core campsite area to become less attractive due to roots, rocks, or uneven soil,”

– Dr. Jeff Marion

Leave No Trace: Be part of the solution

Ann Schwaller of the Superior National Forest shared some ideas for lessening human impacts on campsites in the wilderness. In general, Schwaller says visitors should “treat campsites the way they treat their own septic systems or backyards. I can’t imagine people throwing trash in their toilets at home or burning cans/bottles/plastics in their backyard fire pits.

- Consider camping in smaller groups: This will mean more solitude and less impact.

- Limit tent size and numbers: Consider sharing a tent and use tents with the smallest footprints possible.

- Consider leaving axes and saws at home.

- Use the smallest firewood you can find scattered around the ground: small enough to fit under the fire grate. Large logs and big fires can sterilize the soil and, because they take longer to burnout, are more likely to cause wildfires.

- Gather wood away from campsites: This will ensure the nutrients, vegetation, and soil around the designated campsite remains intact, preventing soil loss, erosion and root exposure.

- Pack food and trash out: Throwing it in the woods attracts wild animals to dig up the ground, further damaging the campsite area.

- Don’t burn trash: Pack it out! It’s generally illegal to burn trash in the State of Minnesota because it becomes toxic to the water and air.

- Keep trash out of latrines: Nothing inorganic should go in the latrines. Food and fish remains invite animals to the site. The faster latrines fill, the sooner new ones are needed, which can further expand the site.

- Watch where you walk: Trampling vegetation causes more erosion, destabilizing soil and leading to compaction and less growth.

- Speak up, say something: If you see somebody in your group damaging natural features, like trees and rocks, ask them to stop.

By Greg Seitz

Read more in Wilderness News Spring 2015 >