Fire has shaped the Boundary Waters since the last glaciers, it has helped create the iconic woods which surround the water, periodically incinerating the understory, releasing seeds, and returning nutrients to the soil.

“While the post-fire landscape can look shocking and desolate in the immediate aftermath of a fire, vegetation starts to recover fairly quickly,” says Eli Anoszko, an ecologist at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point, who has studied fire in the Boundary Waters region extensively. “Recently burned areas are prime areas for blueberries and raspberries and also important habitat for species like ruffed grouse and moose.”

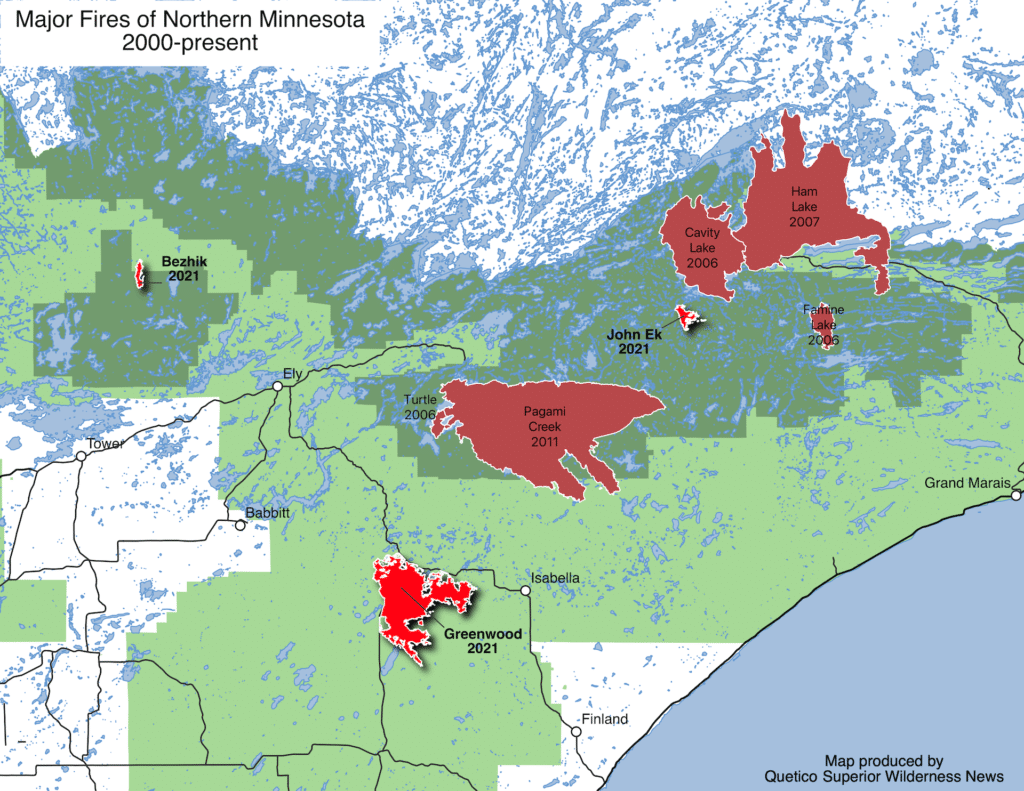

Fire is also one of the most dangerous and uncontrollable elements in nature. It threatens life and property. The summer of 2021 has proven to be a particularly active fire season. Major fires have burned in the Superior National Forest and the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. That includes the Greenwood Fire, which is the largest in 10 years at 26,000 acres.

How much of the Boundary Waters has burned?

This year, less than one percent of the Superior National Forest and BWCAW have burned. It is a severe fire year, but previous research has helped put it in context.

“For example, in 1863-1864, 445,000 acres burned covering almost half of the current BWCAW!” Anoszko says. “In 1875, close to 224,000 acres burned and in 1894 169,000 acres burned in the current BWCAW. Over a 31-year period, the equivalent of 86% of the modern BWCAW burned.”

With fire in the news and everyone concerned about its consequences, we’ve assembled some frequently asked questions to help readers better understand the power and role of fire in canoe country.

Are wildfires bad for the Boundary Waters forest?

“Generally no, boreal forests are well adapted to fire and some species like jack pine actually require fire to regenerate,” Anoszko says. “Pioneering research by Miron ‘Bud’ Heinselman has documented the long history of fire in the BWCAW and we know that most forests in the wilderness originated following catastrophic wild fires.”

But, not all fires are the same. One big difference that dictates their impact is the time of year when they burn.

Anoszko studied the aftermath of two large Boundary Waters fires about 15 years ago as part of his PhD research. The 2006 Cavity Lake Fire burned in later summer, while the 2007 Ham Lake Fire burned in early May.

Late season fires, like those burning right now, tend to be more intense than spring blazes, burning away almost all organic material. During less intense spring fires, plenty of trees might be killed, but seeds and roots in the soil may survive.

“In general late season fires like the Cavity Lake fire result in slower recovery and sparser regeneration after fire than do early season fires because they leave less behind,” says Anoszko. “That’s not necessarily a bad thing, for example, many conifers including jack pine struggled to regenerate within the Ham Lake Fire because the charred organic soil left by the fire wasn’t a good seed bed for them. Late season fires tend to expose more bare mineral soil and can provide better seed beds for conifer regeneration.”

Were this summer’s wildfires caused by climate change?

A definitive answer is not possible. But this summer’s conditions are a “harbinger of things to come,” says Anoszko. If carbon emissions continue at their current pace, wildfires are expected to double by the end of the century.

“I think this year is a good example of the types of conditions that we can expect in the future, but it’s difficult to attribute any single event or year to climate change,” Anoszko says.

Other climate impacts on the region’s forests that are already being observed include an outbreak of Eastern Larch Beetle in northwest Minnesota, more storm damage, and the decline of many northern species.

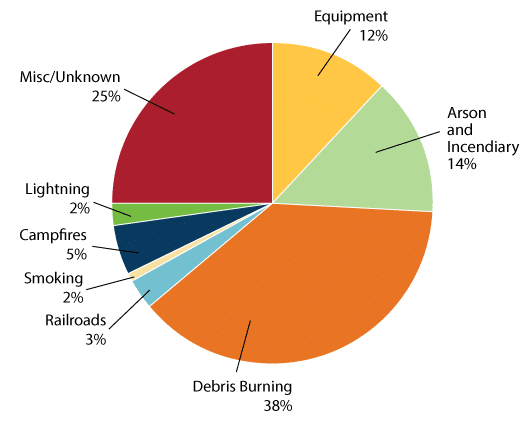

What is the most common cause of wildfire?

Almost all wildfires in the United States are started by people: about 85 percent. In Minnesota, almost 4 in 10 fires are caused by burning debris. Five percent are caused by campfires. Two percent are caused by lightning.

Most of the major fires in Minnesota in 2021 have been started by lightning, including the large Greenwood Fire. The catastrophic Ham Lake Fire in 2007 was started by a campfire that escaped control.

How did Native American people use fire in the forest?

Indigenous people used fire for multiple reasons in the boreal forest. Recent research into prehistoric fire shows frequent fires occurred along popular travel corridors, where fire was used to keep the understory open.

“Fire produces many environmental responses, including increased blueberry production, fewer ticks and flying insects, and more open, ventilated, and accessible forest conditions.”

– Researchers call for restoring human-forest connections in the Boundary Waters

The modern practice of suppressing fire as much as possible has reversed these trends.

“[T]he reduction of Anishinaabe land use practices, including fire use, coupled with wilderness designation has produced a more homogenous, densely forested landscape that is both more susceptible to catastrophic fires and less resilient to droughts when both disturbance processes are predicted to increase in frequency and severity in the future,” researchers wrote.

When was the BWCA last closed due to fires?

1976. That is believed to be the only other time, when another historic drought gripped the region, and large fires ignited in the wilderness. The wilderness was closed for most of September and October that year.

“A BWCA fire which extended over more than 1,000 acres flared up in late August west of the Gunflint in the Saganaga, Seagull, and Magnetic Lakes area,” Quetico Superior Wilderness News reported in 1976. “More than 200 campers were evacuated.”

The Boundary Waters was closed due to threat of fire August 21, 2021 and lifted September 3 with a few restrictions.

When a wildfire happens, what makes it bad enough for us to intercede?

Forest Service policy is generally to allow fires to burn in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness — if they do not pose a threat to people or property outside the wilderness. The Superior National Forest’s overall management plan lays out goals for the BWCAW intended to keep it as natural as possible.

“Natural successional changes and those associated with natural phenomena, such as fire or windstorms, will be the dominant force in ecosystems,” the plan says. “Vegetation will be managed only to protect wilderness values or adjacent property.”

Forest Service policy also calls on managers to “allow lightning-cause fires to play, as nearly as possible, their natural ecological role in Wilderness.”

With such dangerous fire conditions, and too few firefighters, airplanes, and other resources, most fires are currently being suppressed as quickly as possible because of the threats they pose. The Greenwood Fire, outside the wilderness, is receiving most firefighting efforts right now, with minimal management occurring in the Boundary Waters at this time.

When there is mature forest, how often do wildfires typically happen?

Research has shown that before logging, fire suppression, and other activities disrupted the natural cycles, most forests in the Boundary Waters region burned about every 100 years.

“These forests don’t burn all that frequently but when they do the fires tend to be large and difficult to control,” Eli Anoszko says. “While all fires depend on having the right mix of fuel and weather to burn, the climate of the boreal region is such that in most years the fire season is very short. While there are always a few fires in the BWCAW and Quetico-Superior Region, it is the drought years that account for the vast majority of fire starts and acres burned.”

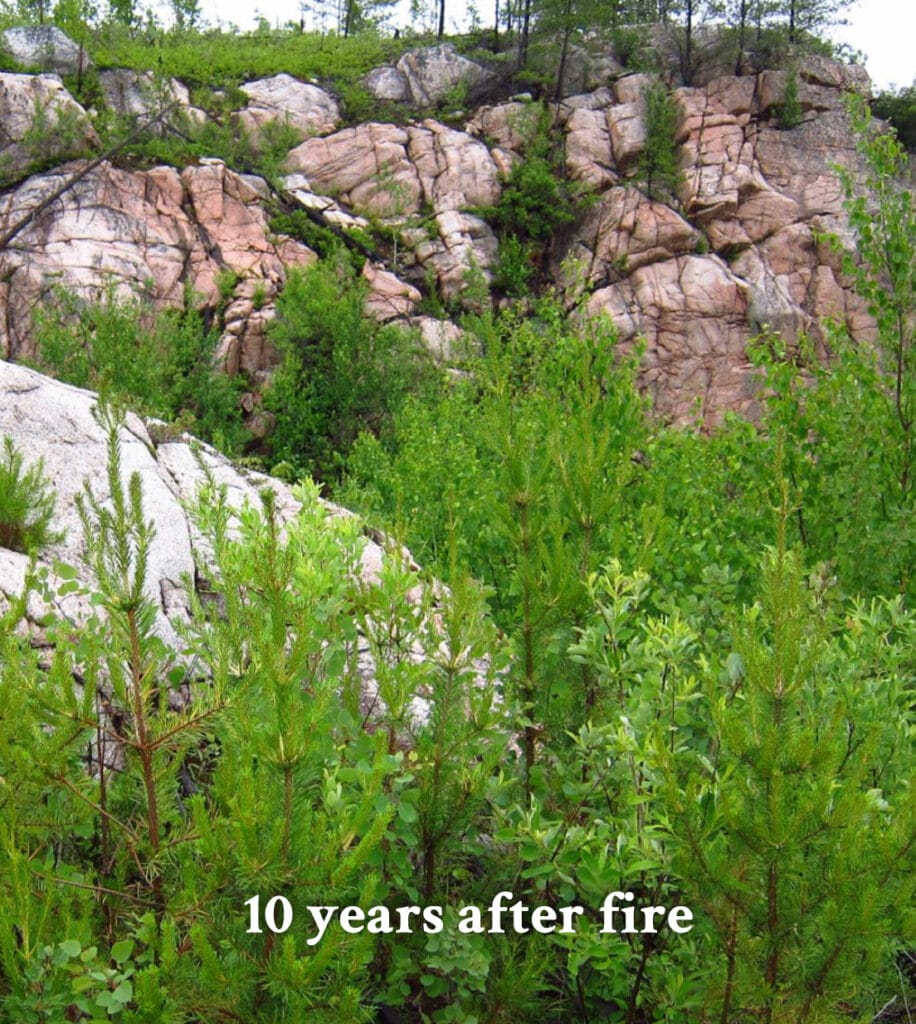

How do forests regrow after wildfires?

“The first 1-5 years after a fire are typically the most critical for determining what the future forest will look like,” Anoszko says. “Regeneration during this time depends on the timing of the fire, the seed bed conditions and any surviving trees or underground root networks for species like aspen, maple and birch. During these first few seasons vegetation changes rapidly.

He says often, a burst of ephemeral wildflowers like Bicknell’s geranium and pale corydalis and shrubs like blueberries, raspberries and serviceberries may grow. At the same time or shortly after, tree seedlings begin to grow.

“Once these trees get established they start to form a canopy anywhere from 5-15 years after a fire,” Anoszko says. “This initial canopy is often composed of shade intolerant and fast growing species like jack pine, aspen and paper birch but quite often shade tolerant and slower growing species like spruce, fir and cedar establish alongside the fast growing and light demanding species.”

Between 10 to 30 years after a fire, forests can be dense and difficult to walk through. It will slowly open up as trees die and insects and wind are felt. About 50 years after a fire, the forest will appear mature.

“Eventually there may only be scattered large jack pine or aspen snags or super canopy white pines amidst a forest of multi aged spruce, balsam and cedar as the shade tolerant species continue to replace one another,” Anoszko says. “These mixed conifer forests continue to shift and change over time until the next fire comes.”

He adds that late season fires like this year’s blazes generally result in slower regrowth than early season fires.

What happens to animals during wildfires?

Some escape, and some don’t. It is believed that many healthy animals are able to sense fire danger and move away. Many animals that die in wildfires are the young, old, or sick.

Another question is what happens to animals without wildfire? Fires help create different types of forest, which are preferred by different species. Some animals would not have any habitat without occasional fires.

How can I help?

Prevent wildfires. Even though fire is a natural part of the Boundary Waters forest, it is safest when managed through prescribed burns, allowing managers to choose the time and place. Consult Smokey Bear’s website to learn how to be safe with campfires, debris burning, and equipment operation.

Support local residents and organizations. Several local volunteer fire departments have been an instrumental part of fighting fires this summer and every year. Donate to the Gunflint Trail Volunteer Fire Department.

Support sensible fire management. Prescribed fire and firefighting are expensive, resource-intensive activities. Citizens can support efforts to increase budgets and help bring back fire to landscapes in controlled, beneficial ways.

Slow down climate change. With wildfires expected to double in the decades ahead, actions to reduce carbon emissions and minimize global warming are important. This will help preserve the type of climate in which the Boundary Waters ecosystem evolved, or at least slow down the speed of change so species can adapt.

What are your favorite books related to Minnesota wildfires?

The Boundary Waters Wilderness Ecosystem, by Miron ‘Bud’ Heinselman. Heinselman was a Forest Service ecologist in the 1960s and 1970s, who studied and publicized the important role of fire in the boreal forest ecosystem. He went on to retire early and advocate for wilderness protection for the area. This book was “the first comprehensive guide to the geology, biology, and ecology of this unspoiled and fascinating area.”

Gunflint Burning, by Cary Griffith. This gripping account details the cause and the response to the catastrophic Ham Lake Fire in 2007. “Cary J. Griffith describes what happened in the minutes, hours, and days after Posniak struck that fateful match—from the first hint of danger to the ensuing race to flee the fire or defend imperiled property to the incredible efforts of firefighters and residents battling a blaze that lit up the Gunflint Trail like the fuse to a powder keg,” the University of Minnesota Press says.