By Charlie Mahler

Fewer visitors are spending the night in the Quetico-Superior region’s wilderness areas compared to 15 years ago, but visits by day-trippers may be on the rise.

Quetico Provincial Park managers report a decrease in wilderness camping visitors to the park that has lasted more than a decade; overnight visits dropped off particularly sharply in 2009. Overnight visitor numbers have fallen on the U.S. side of the wilderness as well. U.S. Forest Service officials charged with managing the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW) of the Superior National Forest have seen a downturn in the number of overnight reservations since 2003. On the other hand, Superior National Forest managers say that overall visitation—which includes day use—to their wilderness remains steady or is growing slightly.

The decline in overnight visits in the wilderness area is likely a reflection of economics, administrative policies, and local conditions, as well as wider demographic factors and trends in the public’s recreational preferences. The changing patterns of recreational use of wilderness could affect the Quetico-Superior for years to come. Counting wilderness visitors to Quetico Park and the BWCAW is not as simple a proposition as it appears. Quetico, which charges overnight campers on a per-person, per-night basis, compiles visitor data directly from those camping-fee transactions. BWCAW managers explained that BWCAW visitation numbers are derived using statistical analysis of tallies of reservations, visitors’ self-issued permits, and other usage categories.

“It’s been a gradual decline each year…perhaps more pronounced in this last year…our higher fees and restrictions on the use of live bait and barbed hooks could be a contributing factor.” Robin Reilly, Superintendent, Quetico Provincial Park

Counting the Visitors

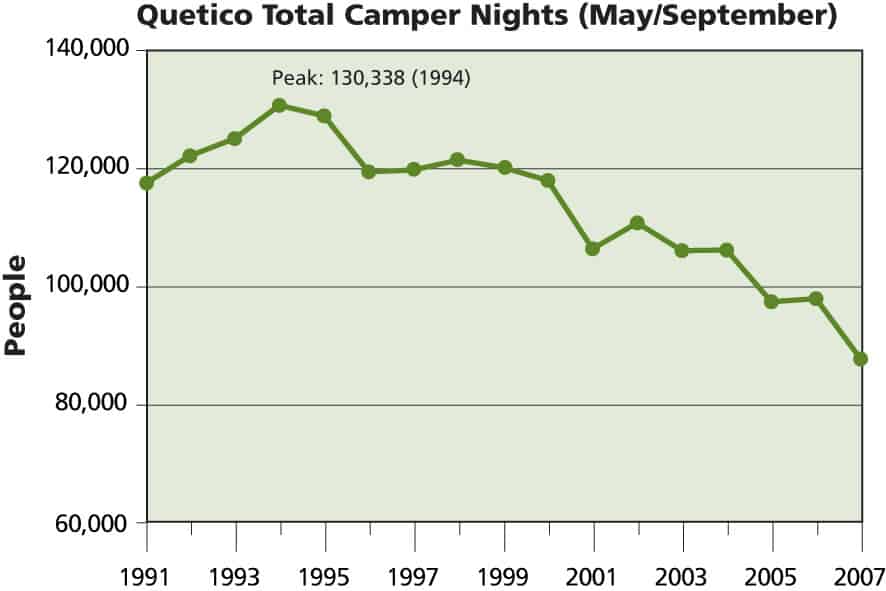

In Quetico Provincial Park, overnight visits to its wilderness interior peaked at 130,338 camper-nights in 1994, according to data compiled by park authorities between 1991 and 2007. Camper-night numbers remained fairly steady at 120,000 between 1996 and 2001, when the count fell further to 105,968 visits.

In 2007, the final year of data supplied by the Park, visits fell to 87,388, marking an 18.6% decline in camper-nights over 13 years, or 42,950 fewer camper-nights. Quetico Superintendent Robin Reilly said that 2008 and 2009 numbers continued the downward trend, which he pegged at 20% off the 1994 high point. (At press time, definitive visitation values were not available for 2008 and 2009 because the reservation system was being overhauled.) Reilly noted that the decline has been “more notable at the south side of the Park than the north. Our Canadian visitation numbers for the same period are up slightly.”

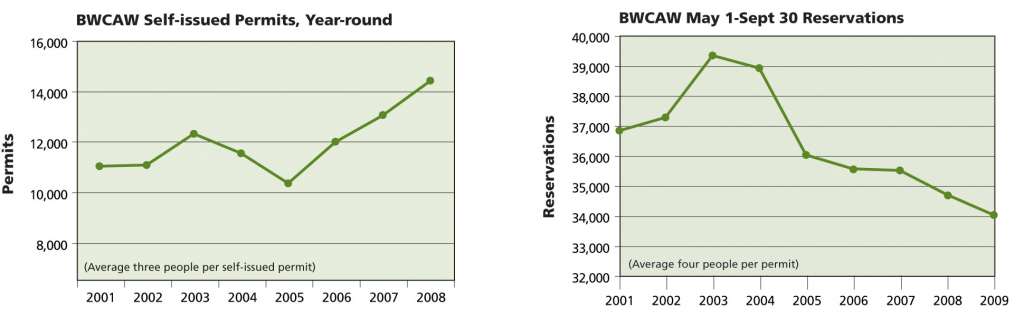

Overnight camping reached its peak of popularity more recently in the BWCAW than it did in Quetico. Summer reservations for overnight visits peaked in 2003 at 39,304. Reservation numbers have declined each year since then, to a low of 34,000 in 2009 – a 13.5% decline in reservations over those six years. An average of four people visit the Wilderness on each permit issued, according to Superior National Forest personnel, so the reduction in permits between 2003 and 2009 equates to more than 21,000 visitors.

What Happened to the Visitors to Quetico Park?

Decreased overnight visitation in Quetico appears tied to its southern entry points. Visitors from the United States typically make their way into the Canadian park via jumping-off points near Ely and along the Gunflint Trail. Reilly noted a host of factors—from post-9/11 upgrades in border security to changes in park policies—that may deter Americans and their guests from visiting the park.

Economics, though, seems a major factor in the decline in visitation from the south. The currency exchange rate between the two countries—which once favored American visitors—has tipped back toward a more even balance, while fees to camp in Quetico have risen relative to those in the BWCAW. Reilly suggested that the decrease in visitors may closely match the decline in the US dollar and rising gas costs.

Still, not all the factors influencing overnight visitors to Quetico are external to the park itself. Reilly admits that recent policy changes inside the Park may have contributed to the visitation fall-off. “Our higher fees and restrictions on the use of live bait and barbed hooks could be a contributing factor,” he allowed. Since 2008, Quetico has prohibited live bait and the use of barbed hooks in the Park. These decisions met with resistance in some quarters which may have resulted in fewer anglers, an important subset of Quetico’s backcountry travelers.

In addition, Quetico’s practice of charging camping fees by the night makes it a more expensive canoe-camping option than the BWCAW. Higher fees for non-residents of Canada and for southern entry-point visitors (who are likely to be non-residents of Canada) can make a typical Quetico trip more than $100 more expensive per person than a similar one south of the border.

In 2010 Quetico will charge each adult visitor from the southern entry points at Cache Bay, Prairie Portage, and Kings Point $20 (CAN) per night to camp in the park’s backcountry. Non-residents entering via Lac la Croix will be charged $16 (CAN) while Canadian residents entering from there will be charged $12 (CAN).

Where are the Visitors to the BWCA Wilderness?

While the number of reservations for overnight camping in the BWCAW has shown a downward trend since 2003, Kristina Reichenbach, Public Affairs Officer at the Superior National Forest cautioned that the reservation numbers don’t tell the whole story of visitation in the BWCAW. Reichenbach noted that the number of reservations made could be influenced by, among other things, the number of motor permits available in a given year; weather, ice-out, and insect conditions in the wilderness, as well as travelers’ familiarity with the electronic reservations process.

Furthermore, more visitors may be making day trips to the BWCAW, rather than having a more extended stay. “It is important to remember that while the reservation statistics reflect a slight decline as reported through the permit system,” Reichenbach said, “our visitor use survey indicates a slow but steady increase in overall visitation to the Wilderness.”

“Demographics indicate that average visitor ages are going up…Some studies say that those visitors are preferring day use and that younger users have less vacation time – they are taking shorter trips and fewer trips.”

Kristina Reichenbach, Superior National Forest, Public Affairs Official

In an effort to track visitor use (including in wilderness areas), the U.S. Forest Service conducts National Visitor Use Monitoring (NVUM) on each national forest every five years. Reichenbach explained how visitors at locations across each national forest are asked a series of standardized questions. Taking a representative sample of visitor use on the Superior National Forest—whether overnight use, day use, or exempt use (for resorts and landowners), the Forest Service uses statistics to estimate total visitation within the Superior National Forest, both inside and outside the BWCAW. NVUM statistics compiled in 2006, the most recent survey for the Superior National Forest, tabbed total Wilderness visitation at 252,601 individuals.

Reichenbach offered the NVUM numbers to support the Forest Service’s observation that visitation to the Superior National Forest is growing slowly and steadily. But data from previous NVUM surveys would not be directly comparable at the local level, she said.

One measure of growth in BWCAW visitation, however, is the number of year-round self-issued permits. Self-issued permits are typically used by summer-season day visitors and early-spring, late-fall, and winter overnight visitors to the BWCAW. The number of self-issued permits has risen fairly steadily, from 10,961 permits in 2001 to 14,325 permits in 2008.

Decreased overnight camping—whether at Quetico or the BWCAW—may be attributed to the age of visitors. “Demographics indicate that average visitor ages are going up,” Reichenbach said. “Some studies say that those visitors are preferring day use and that younger users have less vacation time; they are taking shorter trips and fewer trips.”

Superior National Forest officials are aware that some observers argue wilderness recreation is less appealing to a younger generation of potential visitors. Data on visitors’ age—which may be the most important variable affecting wilderness recreation—aren’t available at the BWCAW level, however. “We are concerned about the general trend reported in today’s society that indicates fewer opportunities for young people to connect and care about natural resources,” Reichenbach said. “As an agency and as a partner with other agencies and organizations, we are stepping up our educational outreach.”

But education outreach and actually attracting visitors are two separate things. The Superior National Forest leaves marketing the BWCAW to its gateway communities and Quetico-Superior area outfitters and guides.

On the other hand, a reduction in some kinds of visitor usage of the BWCAW could have benefits. “For example, if there is a decline in overnight permits, does it indicate visitors are camping outside the BWCAW and coming in for day use?” Reichenbach asked. “If so, it is actually achieving one objective of the 1978 [Boundary Waters] Act, to disperse use on the Forest both inside and outside the Wilderness.”

“If there was a reduction in visitation during the reservation period,” Reichenbach added, “the actual users of the wilderness would likely experience more seclusion and less evidence of other humans.” For the people continuing to visit the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness and Quetico Provincial Park, greater seclusion—and a little more elbow room on the portages—could be the good news in the complex story of wilderness recreation in the Quetico-Superior region.