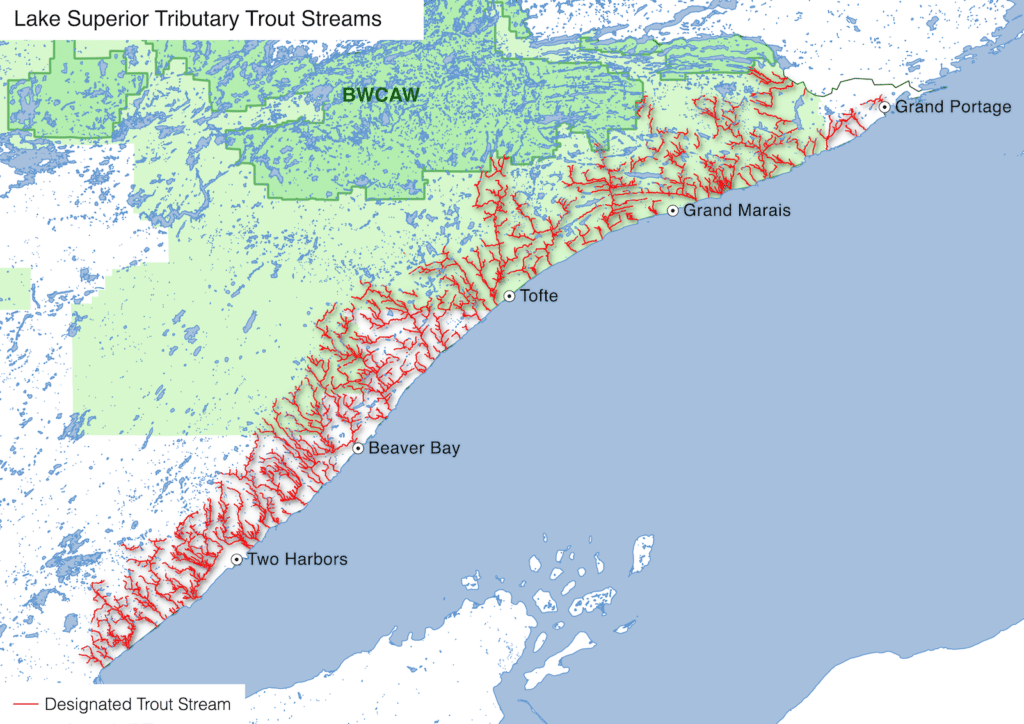

Delicate brook trout have survived in the tumbling streams and rivers that pour into Lake Superior on Minnesota’s North Shore for thousands of years. These beautiful fish thrive only in pristine waters that are cold and clean. For millennia, the North Shore streams were kept cold by towering stands of old-growth pine, cedar, and other conifers.

When Europeans arrived, they found the rugged, rocky shoreline of Lake Superior marked by the mouths of these rivers, which poured out of dark, ancient forests. The shady forests, temperature, food supply, breeding conditions, and habitat was perfect for generations of brook trout.

The Ojibwe people of the Lake Superior region ceded the territory to the U.S. government in 1854 and between about 1880 and 1910, large swaths of North Shore forest were cut down by loggers. For the past century, the streams have been getting warmer and trout have been finding fewer spots suitable for their survival.

Brook trout need cold water, above all else. They can’t tolerate water temperatures above about 65° F. The North Shore streams rise from bogs, not groundwater springs like other Minnesota trout streams. While groundwater can keep a stream cold even in full sunshine, the North Shore streams require deep forest shade to stay cold along their lengths. Losing the mature conifers meant the loss of the necessary shade.

“We need mature forests to ensure we have viable trout streams in the face of climate change,” said Carl Haensel Northern Minnesota Chair, Trout Unlimited.

Deforestation was the first blow, and now climate change could be the knock-out punch. With annual temperatures already increased from 50 years ago, and more to come, the North Shore streams could be heated out of habitability. But, not if a coalition of organizations, agencies, and volunteers can do anything about it.

For the past several years, numerous partners have been strategically planting trees and restoring the forest along these trout rivers as a hedge against climate change. In about 50 years, when global warming is expected to be severe enough to drive out brook trout, the trees will have reached maturity. Then, the big, long-lived conifers should shade the streams, hopefully keeping the water cool enough for the special fish species.

The effort got a major contribution from the federal government recently, when the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative awarded a $200,000 grant to the Nature Conservancy. The funding will make restoration possible on 600 acres of riparian forests, planting and protecting 29,500 trees along 10 miles of Lake Superior tributary streams.

“Through the distribution of Great Lakes Restoration Initiative grants, we are able to serve organizations and communities who are taking local approaches with projects to enhance the health of the Great Lakes ecosystem.” said Gina Owens, USDA Forest Service Eastern Regional Forester.

The planting is necessary because the native forests simply haven’t returned on their own. There weren’t many mature trees left to provide seeds for new trees. The clearcutting laid bare the shallow soil, and in full sunlight it didn’t let large trees or conifers thrive.

The forests became dominated by paper birch and other hardwood species. Whitetail deer, which were not common along the North Shore before European settlement, are now present in great numbers during the winter. They eat any cedar or pine seedling they can find, representing another challenge to regrowth.

Not only will many trees be planted along the streams, but the work will also include fencing trees to prevent deer from killing them before they reach a safe height. This can include enclosing individual trees, or large areas. Singe tree cages are generally used for white pine and cedars, while larger exclosures of up to 20 acres can be created to also help yellow birch.

Planting yellow birch, as well as red oak, in addition to pines and cedars, is a strategy intended to prepare for climate change. Those tree species are expected to grow best in the decades ahead as the North Shore responds to global warming. It should help keep healthy, diverse forests on the landscape, and provide some cool shade for fish.

The Nature Conservancy produced this video about the project:

More information:

- Trees for Trout – The Nature Conservancy

- Superior National Forest: North Shore Forest Restoration Project

- Assessing Impacts of Climate Change on Vulnerability of Brook Trout in Lake Superior’s Tributary Streams of Minnesota – University of Minnesota, Duluth

- The North Shore Forest Collaborative