By Diane Rose, Wilderness News Contributor

Stunning blue skies and calm, summerlike days prevailed across Minnesota in late September, creating ideal conditions to begin a series of planned burns designed to reduce fuel supplies that could feed uncontrollable Superior National Forest wildfires in areas affected by the July 4, 1999 blowdown.

“Conditions were perfect,” said Donna Hart, information assistant for the U.S. Forest Service’s Gunflint Ranger District office. Hart said that all went well as burning began on September 27 and 28 on several relatively small tracts. On those days, 15 acres were burned near Mayhew Lake, approximately 30 miles north of Grand Marais, and 109 acres were burned in several small sections near Iron and Mash lakes. Those areas were not within the BWCA, nor were they top priority on the burn list for this fall. On Sept. 28th, crews completed a burn of the high-priority, 192- acre Skipper Lake tract (40 miles north of Grand Marais and immediately west of Poplar Lake, including 60 acres within the BWCA). Also on Friday, September 28, Quetico Provincial Park officials conducted a 2,000-acre burn in the North Bay area of Basswood Lake. On September 30, another 300 acres of BWCA territory was burned along the Brule River.

However, wind and rain during the first half of October put further burns on hold. On October 15, Forest Service officials called a halt to prescribed burning until at least next spring. Hart said the decision was based on wet conditions at the time and the fact that each burn requires at least three full days without rain, and no rain predicted. “The burns we did complete this fall went very well, and we burned a lot of brush piles – about 3,200 acres worth – that came from material cleared from private property,” Hart said. “We had teams from Montana here working with us and everyone used the old Top of the Trail resort buildings

for housing.”

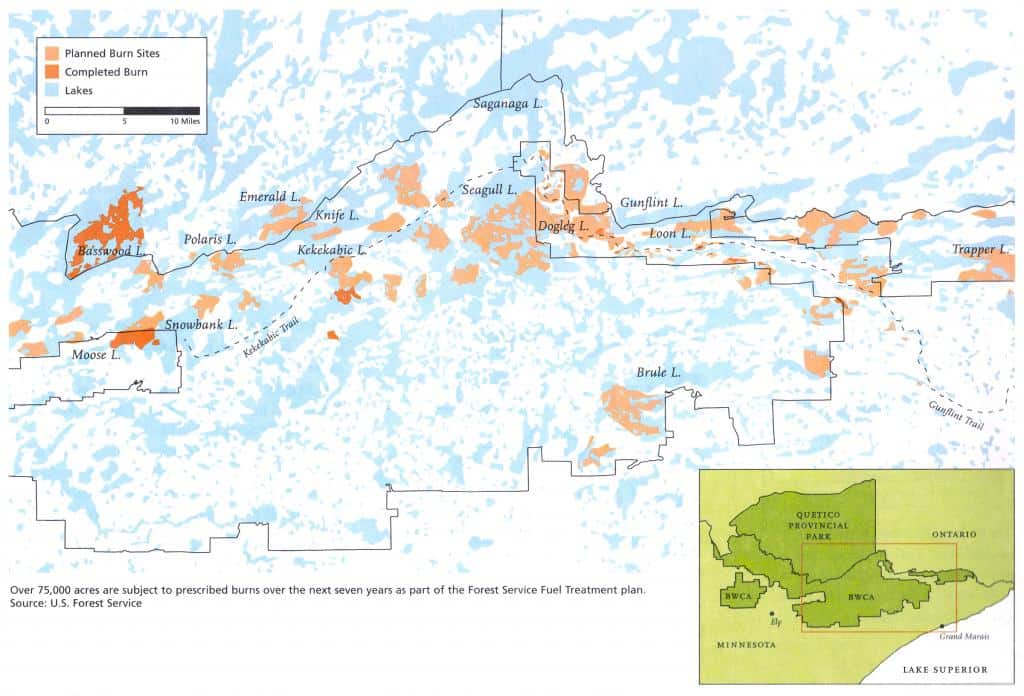

A total of 1,000 acres underwent prescribed burns this fall, 360 of which were within the BWCA. Plans called for burning more than 4,000 BWCA acres this year, and all areas not completed are now on hold until 2002. These include top-priority sections totaling 5,200 acres in the Magnetic Lake and Kekekabic Lake areas, as well as 300 acres near Dogleg Lake.

“Most of what we completed this year were areas along the edges of the BWCA,” said Tim Norman, fire management officer for the East Zone of the Superior National Forest. “We generally move from east to west and work our way downwind, so we’ll be getting further into the BWCA as the burns proceed. Also, we started with the highest resource value areas identified by the environmental impact statement, which are those with homes bordering the wilderness.”

Environmental Impact Statement

The Forest Service has been at work for the past year on the environmental impact statement and detailed plans for each burn. The total number of acres to be burned during a five- to sevenyear period is 75,000 within the 375,000 acres (out of 1.1 million total acres in the BWCA) that were affected by the 1999 blowdown storm, in which straight-line winds over 90 miles per hour snapped and toppled a huge swath of trees. A total of 477,000 acres were affected across the entire Superior National Forest.

The prescribed burn plan that was selected last May, following work on a draft environmental impact statement report and a public comment period, calls for water and foam to be used to put out the fires. Burn areas also were adjusted to reduce the loss of stands of old-growth cedar and pine trees.

Since May, the Forest Service has been developing detailed plans for each prescribed burn tract. This work – which will continue over the coming winter – includes resource surveys, identification of ideal weather conditions for each burn, fire behavior predictions and plans for communication, public notification, logistics, traffic, medical emergencies, traffic and postburn monitoring.

On the day of a prescribed burn, the burn boss cannot proceed before determining current and expected weather conditions and fuel conditions and checking off each item on a detailed “go-no go” list. Hart explained that the Forest Service skips around on the priority list, executing each burn as weather, fuel conditions and suppression resources warrant.

“There are a number of steps that need to be completed for each burn, including public notification, and we have to monitor conditions very closely day-to-day as we decide when to burn,” said Barb Soderberg, wilderness program manager for the Forest Service in Duluth.

The overall burn plan comprises a mix of broadcast burns, patch burns and patch/understory burns. Broadcast burns are planned for large areas where the majority of the trees were blown down. In a broadcast burn, the fire is ignited and allowed to burn over the entire area, leaving a large burned area with islands of standing trees remaining. Patch burns are used to eliminate small, isolated concentrations of blown down trees in the midst of a standing forest, particularly in areas close to the wilderness boundary. A combination of patch and understory burning is used where patches of blown down trees occur within a standing forest of red and white pine. In these areas, small shrubs and trees and material on the forest floor are burned, so that the forest canopy can be protected from crown fires. After this type of burn, there will be small burned areas in the middle of a standing forest that has been opened up underneath.