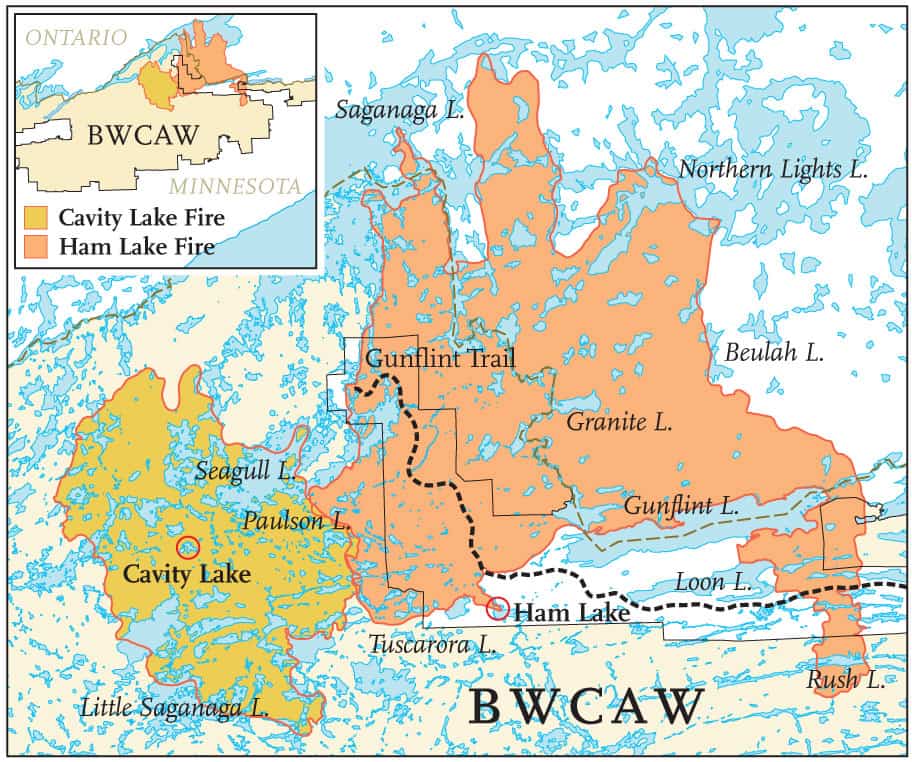

In July of last year, a lightning strike ignited the Cavity Lake fire in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW). Over 32,000 acres burned in what was then called the largest fire in the region since 1894. But it turns out that Cavity Lake was to be only part of the largest fire since 1894. In May of this year, the Ham Lake fire burned more than 75,000 acres right next door.

“The area is essentially dormant during the winter,” says Lee Frelich, Director of the University of Minnesota’s Center for Hardwood Ecology. “With only two months of growing season separating them, as far as the forest is concerned they were one big fire.”

This one-fire reality is easy to see from a hill on the portage between Seagull Lake and Paulson Lake. “As you look to the west,” says Frelich, “everything is the Cavity Lake fire. As you look to the east, everything is the Ham Lake fire. The land is black as far as you can see, all the way to the horizon.

The Ham Lake fire started from a campfire on May 5th. “The conditions that day were just incredible – off the charts,” says Frelich. The region was in a prolonged drought (“You could pick up a handful of dirt and throw it into the air and it looked like flour.”) winds were gusting from 30 to 40-miles-an-hour and lasting all day and night. “Even one little spark is going to blow up into an uncontrollable fire within a few minutes under those conditions. And that’s what we saw.”

The “we saw” isn’t figurative. Frelich and two companions were camping on Seagull Lake when they saw the first plumes of smoke on May 5th. They watched as the fire moved rapidly northwest from Ham Lake, hitting Seagull Lake’s east shoreline and moving around it toward their campsite. They were relieved when the wind shifted to the west and pushed the fire northeastward away from them. “That’s when we made our escape,” says Frelich. (read “Survival” page 2). The fire then burned a wide swath between Seagull Lake and Gunflint Lake further to the east, moving rapidly across the Granite River to burn a large area in Canada. On May 11th, a finger descended back into the U.S. around the east end of the Gunflint. By May 19th, the U.S. portion of the fire finally succumbed to rainfall and the efforts of the firefighting teams.

The ecological impact.

“I don’t think we lost anything ecologically; the real losses are the buildings, and the displacement of people from their homes,” says Frelich. For the forest itself, the fire was a perfectly normal physical event; in fact, this type of forest is fire-dependent and all the Ham Lake fire did was allow the forest to begin regenerating itself.

“The fire has also created a rich research laboratory for forest ecologists,” says Frelich. A recent patchwork of fire events is giving scientists an opportunity to study how a forest regenerates after multiple burns over different time intervals. Much of what burned this summer is jack pine forest that had grown in since the major fires of 1910. The fire also re-burned forest that had burned recently in the 1995 Sag Corridor fire, which itself had re-burned an area that had burned over in 1974.

The forest’s regeneration process starts quickly. Jack pine and black spruce seedlings have already begun to take hold, although they only manage a half-inch or so of growth in the first year and will be difficult to spot. But the Bicknell’s geranium, strawberry blight (which is neither a strawberry nor a disease), corydalis and fireweed are growing strong, with the geraniums reaching a foot in height by the end of the summer.

Like many fire species, geraniums bury seeds in the soil that wait for the next fire to come along, however long it takes. One batch at the end of the Gunflint Trail has been awaiting their chance since the 1910 fires. Another part of the Ham Lake fire zone hasn’t burned since 1801, and seeds that will germinate there are over 200 years old. Fireweed has a different strategy: its seeds are always present, but are only successful when fire clears the competition and the canopy.

Another species taking advantage of post-fire conditions is the black-backed woodpeckers. They feed on a beetle that makes its home in the bark of standing dead trees. These woodpeckers are normally considered quite rare in the Quetico Superior region, but started to arrive in strength after the big blowdown in 1999 created a boom in the beetle housing market. Now the recent fires have produced new crops of dead trees for the beetles to live in. “It used to be you’d see one black-backed woodpecker a year up here,” says Frelich. “Now you can sit down for lunch and see five of them.”

Just the beginning?

Despite the press given to forest fires caused by human carelessness, it turns out that the net effect of humans on forest fires in the bwcaw area has been to dramatically reduce their frequency. Based on data from the 18th and 19th centuries, Ham Lake-like fires should burn the entire bwcaw between one and two times per century. But, during the 20th century, less than one-fifth of it has burned. Why? “Two major forces are at work,” says Frelich. “The first, is forest fragmentation. Historically, the fires that burned the Boundary Waters area actually started further south and burned their way into it. But now this rarely happens because there are no longer vast tracts of forest to the south; roads, farms, and development have led to forest fragmentation on a large scale.” And, says Frelich, “much of the remaining patchwork of forest has converted from conifers to less-flammable Aspen.”

“Another major factor in the diminishing frequency of fires is climate change. When the Little Ice Age ended in the late 1800s and the climate started warming again, the weather patterns were actually less favorable to fire, mainly due to higher humidity. For most of the 1900s we just didn’t get the type of fire weather that occurred in the 1700s and 1800s,” says Frelich.

However, the climate change influence may be in the process of flip-flopping. While the early stages of a warming climate are often associated with wetter conditions, further warming tends to dry things out. More frequent droughts (along with earlier springs) set the stage for an increase in fire frequency and size. “It is still too early to say for sure”, says Frelich, “but the back-to-back Cavity Lake and Ham Lake fires may be a harbinger of things to come.”

By Michael Kelberer, Wilderness News Contributor

This article appeared in Wilderness News Summer 2007