By Charlie Mahler, Wilderness News Contributor

The Boundary Waters. The Border Route. Those dividing “B” words have long been embedded in the names used to describe the Quetico-Superior region. The notion, however, that a modern-day international divide cuts through the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness and Quetico Provincial Park usually fades into the remoteness of the place. The region’s ruggedness, isolation, and wildness make the area seem more like a single thing shared by two countries, than something sharply divided. The area evokes vast wilderness, towering pine, and howling wolves rather than border surveillance or the tracking of terrorist interlopers.

But the wilder qualities of the region and modern realities of border protection are intersecting in the BWCAW and Quetico with the news that the US Border Patrol plans to build a new, larger facility in Grand Marais to better monitor the region, and in light of the recently established Secure Borders Initiative which augers a more closely watched,

higher tech northern frontier.

The Quetico-Superior stretch of what is commonly referred to as the world’s longest undefended

border is different already today than it was prior to September 11, 2001, and seems likely to change even more in the coming years.

Tasked with Securing the Border

“We have a job to do and we don’t apologize for doing that job,” Assistant Chief Border Patrol Agent Lonny Schweitzer said by way of explaining his agency’s growing presence in northern Minnesota since the fall of 2001. “We try to do the least amount of impact that we can in the area that we’re in.”

Doing its job, the agency asserts, necessitates a larger Grand Marais facility – one that could support up to 50 agents – and an increased presence in the wildest reaches of the international border in the form of personnel or high tech surveillance or both.

“We always need manpower on the ground but we also are backstopping that with technology,” Schweitzer said, “and then also our community involvement where we go out and solicit the help of folks who live in those areas. We’ve always done that; we’ve been around since 1924.”

Since the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, the Border Patrol, the uniformed law enforcement arm of US Customs and Border Protection, a bureau of the Department of Homeland Security, has ramped up its personnel across the entire northern border with Canada.

“Pre-9/11 there were less than 400 border control agents on the northern border with Canada – that’s from Maine to Washington,” Schweitzer, who is based in Grand Forks, North Dakota, explained. “Since then, what we did within the first year, year and a half, is triple those numbers. We’re slightly over a thousand border-wide.”

In Grand Marais, an increase in local personnel and responsibilities has surpassed the functionality of the 700 square foot office space the Border Patrol has occupied since the 1960s.

The activities of the additional Border Patrol personnel and nature and extent of high tech border monitoring equipment has also raised curiosity. The passage of the Secure Border Initiative and the contract award to Boeing for high tech border surveillance equipment have prompted some to worry that the wilderness nature of the Quetico-Superior will be compromised.

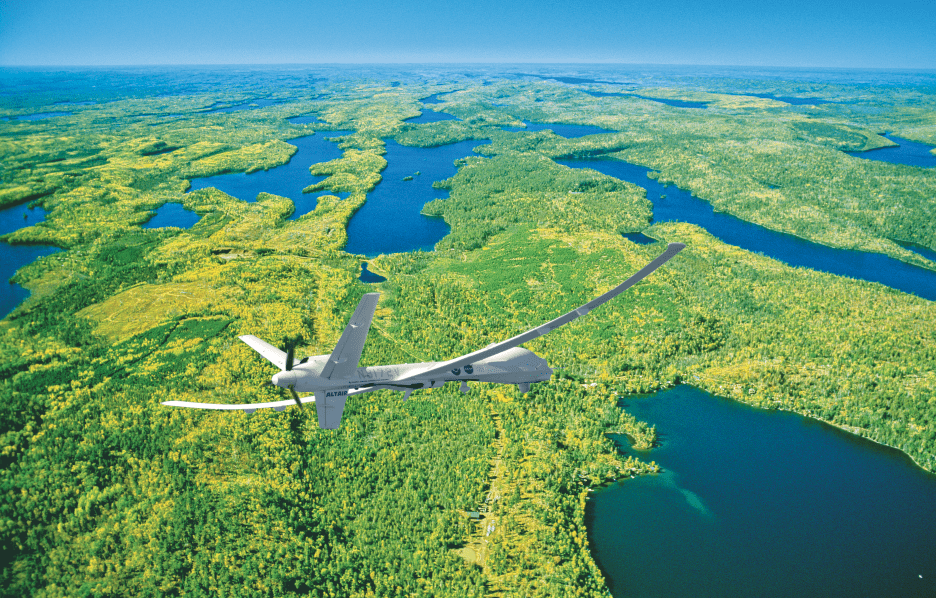

Schweitzer acknowledged future high-tech plans for the border, as well as high-tech measures already in place, but emphasized his agency’s sensitivity to wilderness concerns. “We’ll be assessing the technology we have,” Schweitzer said. “It could be airborne platforms, it could be ground sensors, it could be ground-based radar or ground-based cameras. We have certain things in there at the present time – ground sensors and that – that are unobtrusive and those signals will come back into here so that we are aware of any border incursion.”

Schweitzer, who also noted that the Border Patrol monitors the area via canoes and dogsleds, said the agency is currently assessing where along the northern border resources are most needed and what technologies are appropriate for the task.

“What may work very well in one location, will not work in another,” Schweitzer said offering the difference between the southern border near San Diego and that in the BWCAW. “We can look at some less intrusive technologies.”

Schweitzer stressed that when the Border Patrol operates on land under the jurisdiction of the US Forest Service, like the Superior National Forest and BWCAW, it does so under a “memorandum of understanding” that calls for a “cooperative working relationship” between the federal agencies.

The Superior National Forest’s Public Service Team Leader Barb Soderberg concurred, but stressed that the Border Patrol holds the stronger position in the relationship. “If you’re looking for bottom line,” she said, “the bottom line is they don’t have to ask us for approval for anything. We don’t have jurisdiction over the Border Patrol. I’m sure there are things going on that I don’t know about, and that’s just the nature of the business with border security. If they’re sharing everything they’re doing with folks, it going to be a lot more difficult job.”

“Where the rubber meets the road,” Soderberg added, “if they felt they needed to use a motor boat in a paddle-only area, or if they needed to fly below the 4,000 foot level, they do not have to ask our permission. But I do know they are interested in the fact that it is a designated wilderness area.”

Soderburg said the Forest Service has provided the Border Patrol with the BWCAW user education video, has offered to help in Border Patrol training sessions, and has provided knowledge of routes into various areas of the wilderness.

Soderberg refused to speculate about how the Forest Service would react to a Border Patrol request to build structures or clear forest in the Wilderness. “That’s total speculation. They have never asked us or made us aware of that kind of permanent mark in the wilderness. I don’t even want to speculate at this point,” she said.

Concerns About What Might Change

In Grand Marais, a group of concerned citizens is troubled about the increase Border Patrol presence in the area. Their concerns range from the future of the wild character of the BWCAW to feeling left out of discussions about the growing role of the Border Patrol in their community.

“The Boundary Waters is considered a national treasure,” Grand Marais’ Staci Drouillard of the loosely affiliated Concerned Citizens for Cook County said. “It took an act of Congress to create the wilderness, and I think it should take an act of Congress to make any changes whether it’s for national security or not.” Drouillard is concerned less about the new Border Patrol building, per se, than she is the manner in which site selection and public involvement is being handled. “I don’t think anyone is concerned about the Border Patrol having a new building,” she said. “The whole thing has sort of been masked in secrecy. They’re sort of discounting the local implications.”

“I think the overarching issue is the militarization of the Canadian border,” she said. “We’ve been tracking the US Coast Guard live fire exercises on Lake Superior as well as the border security and Border Patrol increases. I think the Border Patrol needs to clarify what their intentions are.”

A View From The North

Like Drouillard, Quetico Provincial Park Superintendent Robin Reilly sees the atmosphere on both sides of the border as having changed in recent years. From Americans wondering whether they need passports to visit the park – they don’t, but they will soon need them to return to the US legally – to a more literal interpretation of the treaty that defines the area, the wild borderland has changed.

“There are certainly times now when airplanes flying around the border, because of landing, may have come into US airspace on the way in or something,” Reilly said. “There’s a lot more nervousness about that and a lot more announcements on the radio. There have been people flying bush planes that are seeing fighter planes in the area talking to them about what they’re doing. Not that you say harassment, just that ‘somebody’s watching’ is a much stronger sentiment.”

Reilly observes that as Americans ratchet up border monitoring, the Canadian government often follows suit. “There’s two sides to the border,” he notes. “On our border, you see a tiny bit more concern about border security and interpretation of things literally. To be honest, as a Canadian, my perspective is that as you folks feel a need to tighten up the border, we get pushed into tightening up the border too so that we aren’t perceived as being slack. It’s kind of a ‘me too –ism.’”

Reilly noted that the Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842 allows citizens of either country to travel along the border freely. A more literal interpretation of the treaty nowadays is excluding activities that were typically allowed. “At one point, ‘moving through’ would have included stopping and swimming or fishing for a minute,” Reilly explained. “It’s increasingly being interpreted more literally as ‘keep moving,’ ‘don’t stop.’ It’s a slightly narrower interpretation of things.”

Although he’s unsure of just what American officials have in mind for the border, he’s concerned about what he hears and what it might mean for his park and the entire Quetico-Superior region.

“We hear, essentially rumors, about whether there are going to be jet boats patrolling Basswood Lake,” Reilly said. “Are there going to be monitoring towers along the border – there were announcements about 800 towers along the Canadian border – are there going to be one or two near Quetico? The talk of those things gives people a bit of grief because it flies in the face of their affection for the idea of a wilderness area that spans the border.”

Reilly worries about what increased security activities on the border could mean for the experience of visitors to his park.

“In a sense, Quetico feels twice as big because of the Boundary Waters and the Boundary Waters feels twice as big because of Quetico, to the people that use them. The more you reinforce and put towers and boats and a presence along the border, each of them, perceptually feels like it shrinks by half.”–Robin Reilly, Quetico Provincial Park Superintendent

“In the larger sense of what the experience has historically been,” he added, “which is to say an area that was, a hundred years ago, construed to be a large, transnational unit, too rigorous a presence at the border would take away that experience entirely.”

Factors beyond those that usually impact the Quetico-Superior – national security, the war on terrorism – are likely to drive the future of the area more than ever before. Short of a change in the trajectory in those areas, however, the wild, open feeling that the Boundary Waters and Border Lakes region has long enjoyed seems likely to tighten in the coming years. There is a “boundary” in Boundary Waters after all.

This article appeared in Wilderness News Fall 2006